This post has been updated.

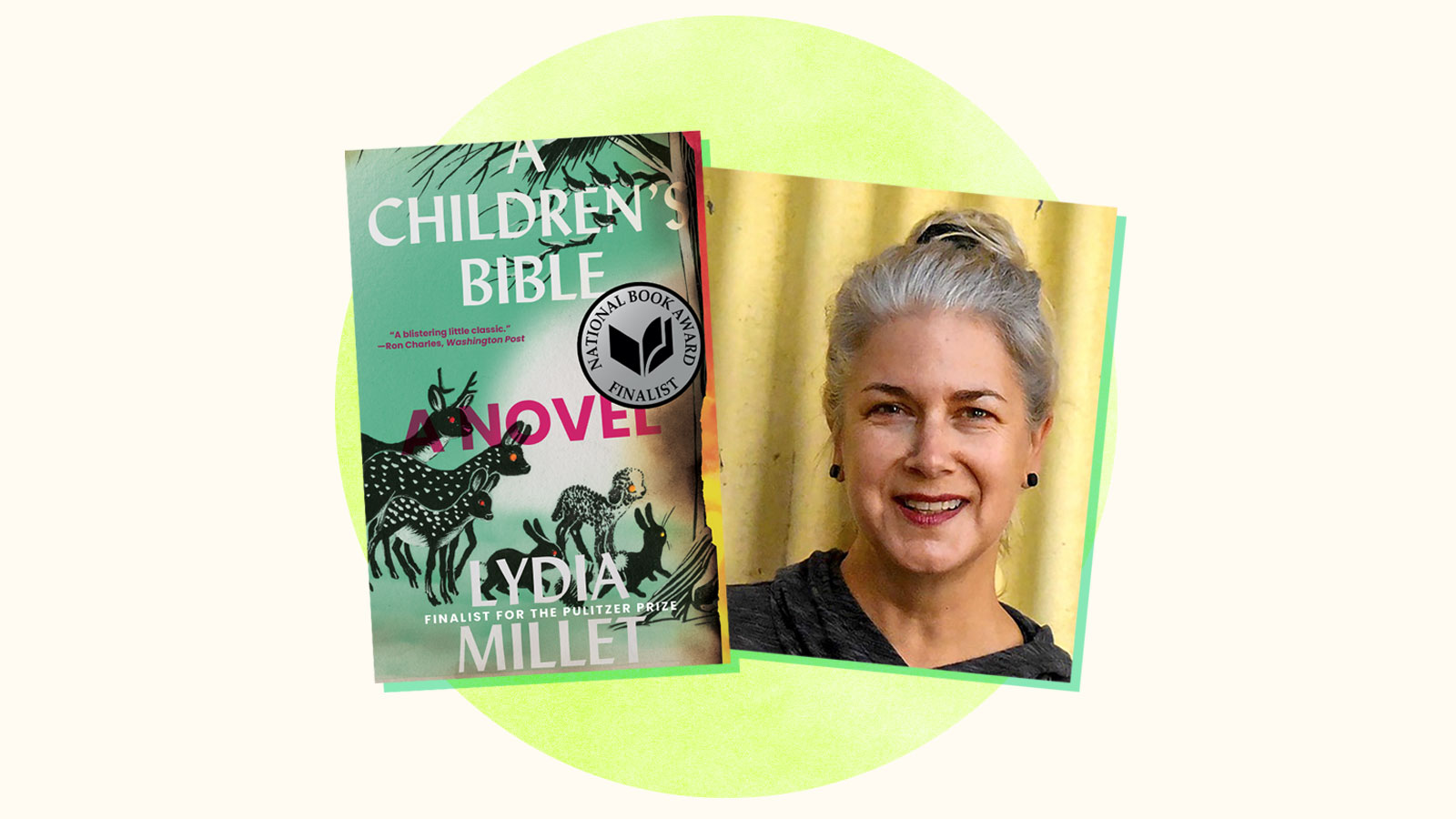

To any young person alarmed by the climate crisis — and frustrated with their parents’ generation for not doing enough to avert it — Lydia Millet’s latest novel may hit eerily close to home.

A Children’s Bible begins with a group of kids and their parents who are vacationing at an oceanside summer home. The adults are languorous — they spend their days dulling their senses with booze, gambling, and waiting for mealtime to roll around. Even when a summer storm causes a flood of biblical proportions, the parents turn out to be more or less useless; after some initial attempts to storm-proof the house, they quickly retreat into the numbness of their usual vices. Specifically: Ecstasy, bourbon, and sex.

A world-changing flood isn’t the only biblical theme in the book. Early on, one of the youngest kids, Jack, finds a literal children’s Bible and begins making connections between its symbols and the surrounding world. In the wake of the flood, he becomes a modern-day Noah, rescuing animals in pairs. Later on, a baby is born in a barn. There’s even a crucifixion.

W.W. Norton

After the flood, Jack and the other children set off on their own, fleeing to find a safe haven. The book’s 12 angsty teens and tweens are exasperated with their parents — with their hedonism, their denial, the way they cling to the status quo even in the face of catastrophe. “Had they had goals once?” the teenage narrator, Eve, wonders. “They shamed us. They were a cautionary tale.”

“I do feel that there has been something stuporous with my generation’s response to the life-support crises that we’re seeing,” Millet told me. “Something really dulled — a kind of stunned, passive fatalism.”

Communicating the climate crisis can be difficult, but with her latest novel, Millet deftly rises to the occasion. She has plenty of experience, having written often about climate change and mass extinction in previous works of fiction, in op-eds to the New York Times, and for conservation groups. She has a master’s degree in environmental policy and spent more than 20 years with the Center for Biological Diversity, first as a staff writer and now chief editor.

A Children’s Bible was one of five finalists for the 2020 National Book Award for fiction. Before a winner was announced on November 18, I spoke with Millet to hear her thought process behind the book. Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q. What inspired you to write about the tension between parents and children?

A. It’s something I had been observing in children and young people. There was just this sort of righteous rage about climate and extinction and other matters of monolithic stature that I hadn’t really observed in my own generation at their age, or even now. People of my general age bracket, we just had this kind of complacency to us. For as long as I can remember, we’ve been willfully turning away from anything that seems overly dramatic, overly earnest, overly serious. I wanted to write about the way that might play out in this particular scenario, where I populate a summer house with this group of families.

Q. You have two kids. Did your role as a mother shape the way you wrote the book?

A. Yeah, I mean they’re both smart and aware, as you can’t really help being when you’re growing up with this stuff. They’re 16 and 12. But I wouldn’t say that either of them is distinctive for their anger. But I have seen it in some of their friends.

The dynamics in the book aren’t based on my personal life, but I think that if I were a kid now, I would be part of that rage. I am part of it, even as a middle-aged person. I like that there seems to be so much solidarity in the rage among the young, a kind of a community.

Q. Denial is also a big theme in your book. I think when people usually imagine climate denial, they think of the really hardcore deniers rejecting science on one side, and then the climate activists on the other side. But you add some more nuance to the idea of denial — it’s about inaction, rather than the rejection of science.

A. I think that’s what we’ll be facing with the next administration, that sort of middle-ground denialism. It’s not anti-science, it’s just a sort of slow, compromise-based grappling with incremental change, where no powerful interests are threatened. It’s about all cars turning electric or something like that — turning away from the notion that radical social transformation is needed from the top down to prevent extraordinary chaos from occurring.

I really think we’re more used to seeing this than the radical denial of President Trump or some GOP members of Congress. What we’re used to seeing is the middle-of-the-road denial that we can sort of slowly and politely talk our way into salvation. But actually we can’t, and the science tells us very clearly that we can’t. Really what we need is a profound shift away from our habits of being in this culture and in cultures across the world. Normally, the denial that we practice is a much softer, gentler denial, but it will probably take us to the very same place if we let it.

Q. Where did you get the idea to incorporate biblical allusions into your novel, and then to literally insert a children’s bible into the book?

A. I have lived with the greatest hits of the Bible for a long time. I was raised in a very secular home, but both my brother and I proved to be interested in religious myths. I’m really interested in how religions persist and don’t persist in the modern American mainstream, in the psyche. And this particular book seemed to lend itself to a kind of Old Testament narrative because I knew that I wanted to have this flood at the beginning. And I just thought, why not peg it to the greatest hits, you know? Genesis and Exodus, and then forward toward Revelation.

I didn’t want it to be any kind of literal mapping — I just wanted it to include these parallels and coincidences. I certainly didn’t build the whole structure on it. Frankly, I don’t have the biblical expertise to do that. I’m only very selectively interested in scripture. I won’t sit down and just read through Leviticus with great joy or anything like that. I’m interested in the melodrama of the Bible, and I just wanted a piece of that melodrama for myself.

Q. I know in the past you’ve written about the extinction crisis, and you have a particular interest in animals. Did that play into your decision to bring in Noah’s Ark?

A. I’ve always been transfixed by that story. I am so obsessed with animals, although not in the way that a biologist would be. I’m constantly fascinated by just the being-ness of animals. As I get older, I just find them more and more enrapturing. I can stare at them now in a way that would have bored me even 10 years ago. I think also that I’m worried for them. When I see birds or lizards or deer or many other creatures, it’s more emotional for me than it used to be. Their existence seems to be vested with the possibility of demise, you know? They seem to almost flicker before my eyes whenever I look at them.

Q. Toward the end of the book, one of the youngest characters, Jack, has this revelation where he makes a connection between science and Jesus. Do you think that’s the kind of revelation we need more of?

A. Yeah, it’s a playful little series of parallels, but I do actually think that that is the kind of symbolic meaning-making we need to engage in more. For example, many of us who are Christian in this country — and even those who don’t share my politics — believe that Christ died for our sins. He died to save us, making a sacrifice for the good of the people, for the common good. And I think it would be very appropriate for many of us to look at those sacrifices and to say, “We need to make that kind of sacrifice in our lives for our children, to redeem them and to and to save them.” That kind of story, I think, needs to be told around matters of climate change and social transformation.