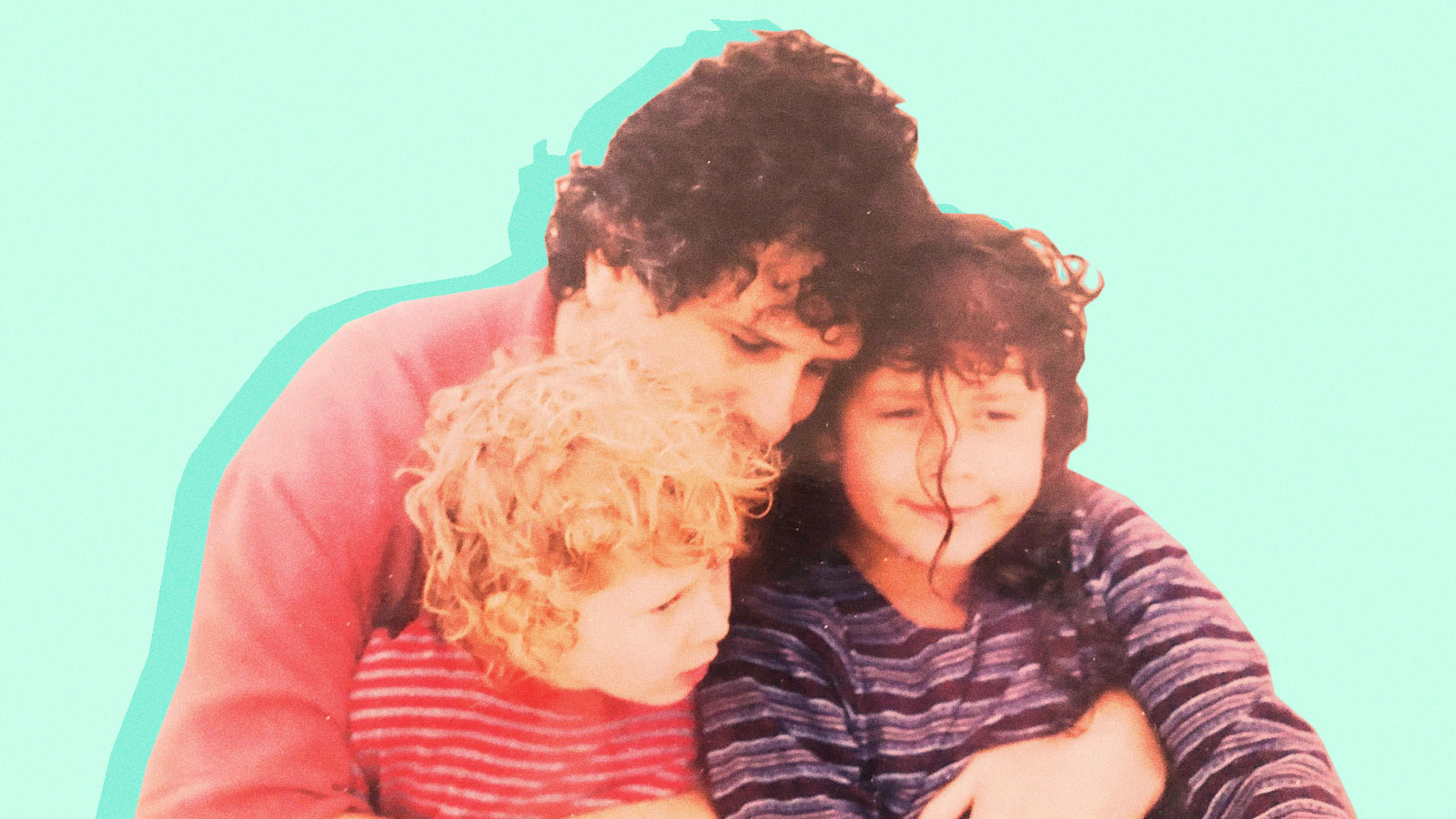

My dad loves letters. When my brother and I were kids, he encouraged us to write letters to our future selves, short chronicles of our daily lives meant to be opened five or 10 years from the time of writing. I recently found one of those letters, written by a 16-year-old Zoya in 2011, that was clearly intended to be read by a much cooler and more successful version of herself. “I must sound really young to you,” I wrote. “Or me. ‘Cause you’re me. WEIRD.” The magic of opening those letters was catching a glimpse of who I used to be. The world looked more or less the same, but I had changed.

A couple of months ago, my dad sat down to write me a letter. “I just want to share my thoughts about how important journalism is, and how essential and meaningful,” he began, encouraging me to keep writing. “It may seem like the field is crumbling but I really think the power of good journalism is more relevant than ever, especially related to the endangered earth.”

He wrote the letter little by little, coming back to it now and then when he had time to jot down his thoughts. As the weeks dragged on, something strange happened: My dad stayed more or less the same, but the world changed. By the time he finished writing the letter, it had absorbed a different thesis statement through osmosis. It wasn’t just a father encouraging his daughter in her journalism career anymore. My dad, who is a composer, a religious Jew, and an innately thoughtful human being, was grappling with the meaning of the virus.

In a wildly popular Q&A that appeared in March in Harvard Business Review (an unexpected place for such a thing), David Kessler, the leading expert on grief, submitted for our consideration a sixth stage of grief in addition to the conventional five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. That stage is meaning. “I did not want to stop at acceptance when I experienced some personal grief,” Kessler explained. “I wanted meaning in those darkest hours. And I do believe we find light in those times.”

“I do think this virus is a kind of parable,” my dad wrote to me, unknowingly echoing Kessler’s sentiment. “What does it mean?”

I feel the urge to pause here and shield my father from the wrath of people who might read this and think that my dad — who considers stepping on salamanders a grave sin — regards the virus as in any way a good thing. He doesn’t. But he does think the lifestyle changes forced by social distancing and economic shutdowns are exposing the privilege behind our habits — my family’s, our neighborhood’s, and many middle-class Americans’.

“This corona stop shows us, those of us who have and want so much, that we can indeed push on while having and wanting less,” he wrote. “I don’t know if we are capable of seeing these things ourselves.” Consuming more, flying more, manufacturing more — my dad has long held the opinion that humanity’s unquenchable thirst for stuff and status will doom us all and the planet to boot. Now, he wondered, “What environmental coalition could have convinced the rich world to slow down for a year in this way?”

The question made me think of Extinction Rebellion (XR), the progressive climate activist group that has been trying to convince the developed world to stop grinding away since 2018. I’ve been following their efforts ever since semi-naked protesters with the group’s British contingent glued their hands to the glass gallery of the House of Commons last year, their exposed butts turned to face the chamber where members of parliament were negotiating the terms of Brexit.

XR has succeeded in briefly shutting down much of the city of London, Times Square in New York, parts of Wall Street, and other hubs of activity around the world. The aim is to generate enough public pressure to convince governments to treat climate change like a national emergency. Mass disruption is one of the tools it uses to draw attention to its cause. The coronavirus seems to have checked off that item on Extinction Rebellion’s to-do list.

I asked Jonathan Minard, a documentary filmmaker who has been working with the group’s New York City branch for the past year, whether the pandemic has provided the group with any opportunities to amplify its climate messaging. Rather, he told me, the pandemic has offered the group an opportunity to reflect. It seems that XR, like my dad and so many others, is ruminating on Kessler’s sixth stage of grief. The result of that contemplation, he said, is a new awareness of how much change is possible through collective action.

“The virus has forced us to slow down, but we’re also slowing down to protect each other,” Minard said. That’s the impulse Extinction Rebellion plans to try to harness in the wake of the pandemic, as it turns its now-virtual climate activism apparatus to the problem of rising temperatures during an economic recession.

“We’re not returning to business as usual,” he said. “The world on the other side of this is going to be irreversibly changed.”

I finally received my dad’s letter when I was about to head home to upstate New York to be closer to my family for the duration of the pandemic. I read it on the plane, breathing in and out through an N95 mask in an empty row of seats. I didn’t want to go home — I had a life in Seattle that I wasn’t ready to leave. But a week earlier, a construction crew had ripped the back porch off my building, leaving a hole in the wall where a door had been. I could’ve moved, but I got on a plane because it felt like the stars were aligning and, more importantly, the pandemic felt biblical to me somehow — too monumental and too scary to weather alone. My family, my dad especially — rememberer of Talmudic stories, the designated moral compass of our family unit, the only one of us who prays — could help me find the meaning in it all.

“The world, and people, are not perfect and never will be,” my dad wrote, “but we are adaptable and can be trained to behave differently (we have to believe this).” He put it in writing so I can remember it in five years, 10 years — the next time it feels like the fabric of the world is fraying.

Are you reading this, future self? Have we changed, or are we more or less the same?