If all had gone according to plan, the Constitution pipeline would be carrying fracked gas 124 miles from the shale gas fields of Pennsylvania through streams, wetlands, and backyards across the Southern Tier of New York until west of Albany. There it would join two existing pipelines, one that extends into New England and the other to the Ontario border as part of a vast network that moves fracked gas throughout the northeastern United States and Canada.

For a while, everything unfolded as expected. When the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approved the project in 2014, the U.S. was in the midst of a fracking boom that would make it the world’s largest producer of natural gas and crude oil. Williams Companies, the lead firm developing the project, was awaiting state approval of environmental permits — a largely perfunctory move at the time — and so sure everything would fall into place that it had started clearing hundreds of trees under armed guard along the pipeline’s route.

Yet the developers did not anticipate landowners, neighborhood residents, community leaders, and anti-fracking activists statewide forging a coalition to kill the pipeline. In a landmark defeat, New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation denied the project’s water-quality certificate in 2016, leading Williams to abandon it in early 2020. The land slated to be cleared, the communities fated to be disrupted, and the waterways destined to be disturbed were preserved by a movement that was far from done.

Reaching beyond the Empire State

The defeat of the Constitution pipeline marked the start of an uncertain era for interstate pipelines in New York and beyond. The company behind the Northeast Energy Direct pipeline, which would have carried shale gas through New York into New England, abandoned the project just days before the state rejected the Constitution pipeline. In 2017, developers walked away from the Pilgrim pipelines, which would have funneled fracked oil from New York to New Jersey. In May, state officials denied a key permit for the Northeast Supply Enhancement pipeline, commonly referred to as the Williams pipeline, between New Jersey and New York City.

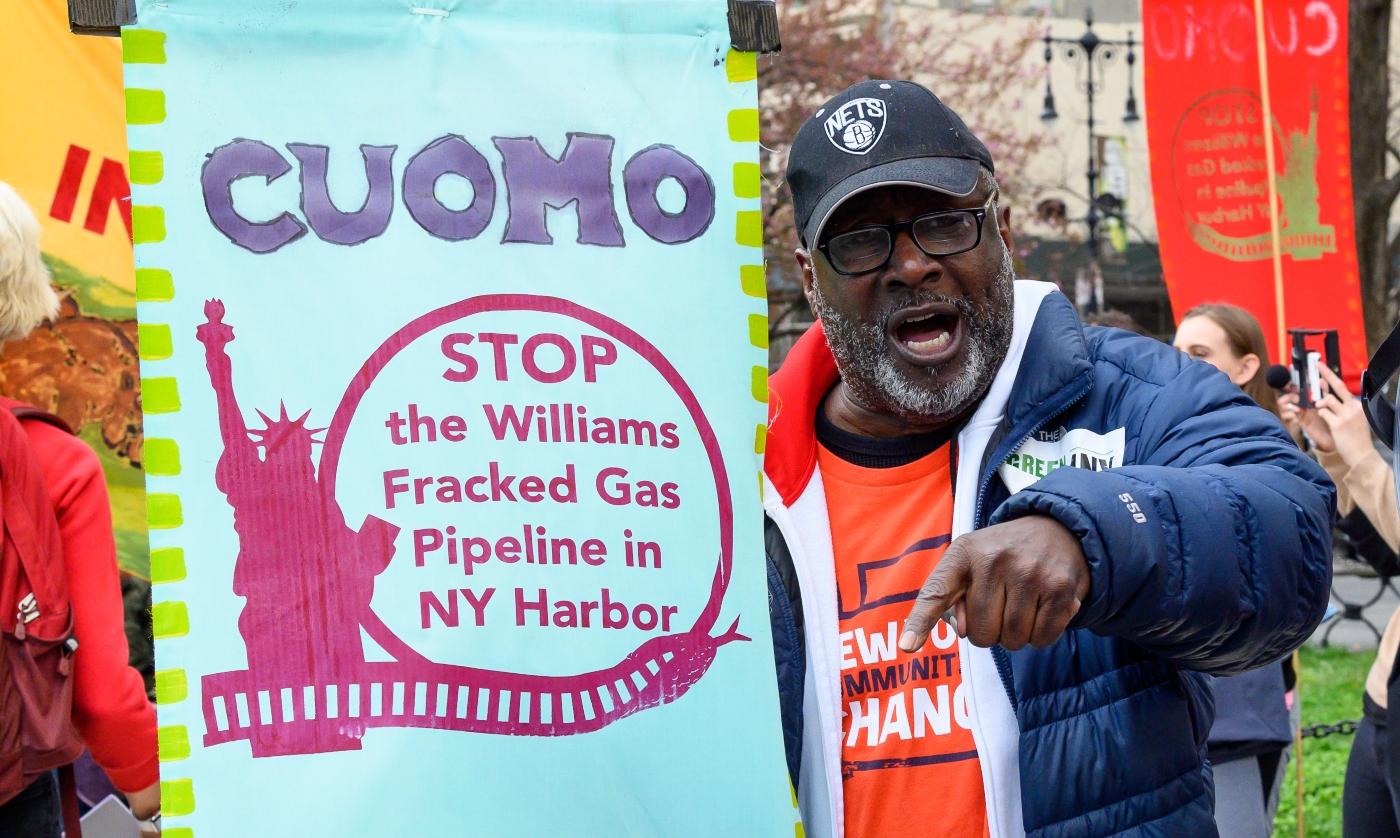

A protestor calls on New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo to halt work on the Williams pipeline in 2018. SOPA Images / Getty

Years of coordinated grassroots opposition prevented the construction of 931 miles of interstate pipeline across the northeast, including 448 miles within New York. These victories impact the entire region — the Empire State is a hub of sorts for a pipeline network extending into New England and Canada. Shutting down a few nodes there can have a profound impact on the gas and petroleum industry’s ability to transport fossil fuels. Activists scored these wins by building large grassroots coalitions — drawing in many people who were new to fighting pipelines — and hammering state officials, especially New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, to use their previously unrecognized authority over interstate pipelines.

“This is smart, good organizing done by groups working together,” said Pete Sikora of New York Communities for Change, which campaigned to stop the Williams pipeline. “This is a ton of work. We ground out huge numbers of events. We lobbied, we protested, we did research reports and studies, and we got local elected officials to oppose the project and start pressuring the governor. It was a very strong in-depth effort over multiple years.”

Forging a multiracial coalition

Much of what the public learned about these pipelines came from activists who conducted research and then held public forums and went door-to-door sharing what they’d found. In the Williams pipeline fight, this outreach focused on New York City’s Rockaway peninsula, just a few miles from where the pipeline would burrow into the ocean floor, stirring up long-settled industrial toxins. “We spent so much time out in Rockaway getting those communities to understand what the threat was and getting them involved,” said Lee Ziesche of the anti-fracking group Sane Energy Project.

Climate activists Rachel Rivera and her 14-year-old daughter, Marisol, joined the Williams pipeline fight early on, incensed that the project would cut close to many of the communities, including her own, devastated by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. “I’m part of the Black and brown community. I’m part of the low-income community. My kids are part of it. They deserve to see a better future,” Rivera said. Marisol said that she joined the fight for the sake of “my generation and for my little sister’s generation and so on.”

The movement became a large, multiracial coalition reflective of the people who would be most harmed by the project. “I think that rang loudly in the governor’s office — to be pushed by a racially diverse, economically diverse constituency and from real people on the ground,” said Patrick Houston, an organizer with New York Communities for Change. In one of the most powerful actions, around 400 people marched across the Brooklyn Bridge, showing “the governor that there is authentic, deep concern about these types of fossil fuel projects,” he said.

Even as the activists increased public pressure, they continued amassing “a really solid record” of scientific reasons why the Department of Environmental Conservation should deny the pipeline’s water-quality permit, said Ziesche. After a three-year fight, the agency did just that for a third and final time, citing many of the concerns first raised by activists, including the risk posed by methane, the main component of fracked gas and an even greater threat to the climate than carbon dioxide.

A new tool in the fight against fracking

Pressuring the state to deny the 401 water-quality certificate has been an instrumental strategy, one first successfully employed against the Constitution pipeline. Activists realized they could sidestep the federal government and focus on convincing state officials to reject that essential permit — a tactic that was underutilized until just a few years ago. “That piece is really important to know because under the Clean Water Act states have really broad authority to set their own water-quality standards,” said Alex Beauchamp, the northeast region director of Food & Water Watch. “Functionally, that gives states a key lever in stopping interstate pipelines.”

Protestors successfully lobbied New York State to deny a crucial water-quality permit for the Constitution pipeline. Erik McGregor / Getty

These movements also built on an earlier push to end fracking that saw hundreds of communities pass measures against the practice. This culminated in a statewide fracking ban in New York in 2014, which became law in 2020. Yet this did nothing to stop the transport of fracked gas or oil from out of state. “We couldn’t stop fracking in Pennsylvania, but we could choke it by stopping the expansion of pipelines,” said Anne Marie Garti, a lawyer and founding member of the Stop the Pipeline coalition that defeated the Constitution pipeline. “Pipelines are useless unless gas is flowing through them, but gas is useless unless there’s a pipeline to put it in.” This approach has helped connect movements across the state. After all, pipelines and other fossil fuel infrastructure are “like veins and little arteries and capillaries,” said Garti. “They’re all interconnected. It’s all one pulsing system.”

While New York has been successful in stopping pipelines, especially large, interstate projects, the fate of some remain uncertain. In 2017, the state denied the water permit for the 92-mile Northern Access pipeline, expected to carry fracked gas through the Allegheny River and Cattaraugus Creek, just upstream from the Seneca Nation. The federal government then waived the state’s decision-making authority, claiming the agency took too long to reach a decision, leaving the future of the Northern Access pipeline unclear. More local fracked gas projects — smaller yet crucial veins in the system — also continue to expand. For instance, the North Brooklyn pipeline, a seven-mile project that would carry fracked gas through predominantly low-income Black neighborhoods in Brooklyn, is still underway, even as a growing grassroots movement repeatedly shuts down the pipeline’s construction and drops banners voicing opposition along the pipeline’s route.

Still, activists find encouragement in their string of victories and believe they’ve reached the point where pipeline developers won’t bother proposing interstate projects in the Empire State. “I double-dog dare any interstate gas pipeline developer to try and ram a project through us,” Sikora said. “They won’t win.”