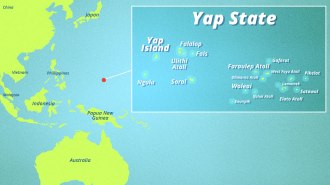

The state of Yap is scattered across the Pacific Ocean, its coral atolls and volcanic islands spanning some 600 miles. Home to 11,000 people, Yap, part of the Federated States of Micronesia, hovers just north of the equator, roughly 1,000 miles east of the Philippines.

Last summer, the state’s health authorities found themselves in a bind. Dengue fever, a painful mosquito-borne disease, was spreading on the main island, and clinics on outer islands urgently needed preventative medical supplies. But Yap’s main means of transportation, a diesel-burning cargo ship, wasn’t working.

Fortunately, there was a backup plan. In early September, hospital staff loaded packages onto two 50-foot, double-hulled sailing canoes, called vaka motus. Ten sailors then zipped between Yap’s islands, hoisting sails and using wooden paddles, ducking into aquamarine lagoons when storms raged. Small engines burning coconut oil gave an extra boost, while solar panels replenished batteries to charge communications equipment. Within two weeks, they’d dropped medical supplies to more than a dozen far-flung islands.

“It was the perfect way to do it,” said Peia Patai, a vaka captain who led the operation. Although the dengue outbreak still persists in Yap and other Pacific Islands, health officials said the vakas helped close an urgent transportation gap.

Patai oversees a fleet of vakas for Okeanos, a nonprofit that builds canoes and trains people to sail them. The foundation operates six vaka motus between Yap and Pohnpei, also in the Federated States of Micronesia, plus Palau, Marshall Islands, and Vanuatu. Okeanos has also built eight larger vaka moanas, operated by independent voyaging societies, which can sail the open ocean.

“I’ve got big dreams,” Patai said by phone. “I want this to grow from two canoes to maybe 10 canoes per country. I want them to start using canoes for sea transportation like the olden days.”

Rui Camilo

For thousands of years, navigators in the Pacific used stars, ocean currents, and wind patterns to guide vessels across vast ocean expanses. Early canoes were sculpted from tree trunks and lashed together with coarse fibers from materials such as coconut palm seeds. But centuries of colonization and disease eroded the canoe-based cultures. Today, many remote islands like Yap rely on oil-guzzling freighters to deliver goods and shuttle passengers; not every place can accommodate airplanes.

In recent decades, a pan-Pacific revival has flourished as navigators preserve and reclaim traditional sailing methods. Patai, who is from the Cook Islands, first learned celestial navigation in 1991, after serving in the Australian Navy. He’s since earned the title of master navigator. Patai says he feels a responsibility to pass this knowledge to younger generations — not only to honor the past, but also to prepare for the increasingly dire outlook for island nations.

“For me, the only way for us to go into the future is to relearn our past,” he said.

Peia Patai, master navigator, Okeanos fleet commander, age 53

“When I was young, you could walk on the reef and collect seashells. Today, there is no more reef; it’s all been covered by water. Water is rising, the weather is totally changed. Typhoons are coming late. It’s not something that we can ignore.

“Whenever a cyclone comes, we’ve learned to accept it and live through it, and once it finishes, you recover. Our people have always been very strong in those kinds of changes, and I think we will learn to adapt to [climate change]. We just have to start making the changes, and hope that those changes will continue to improve.

“That’s the only way we can have a better future, not for us, not for me, but for the younger generations, my children’s children.” Sean Grado

The Pacific Islands are acutely vulnerable to the effects of climate change, which today include increased droughts, water scarcity, coastal flooding, and more powerful storms. Facing existential threats, including the disappearance of entire islands, leaders of these low-lying nations have played pivotal roles in securing international agreements to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

“The most vulnerable atoll nations like my country already face death row due to rising seas and devastating storm surges,” Hilda Heine, president of the Marshall Islands, told delegates at the United Nations climate conference in Madrid in December.

“It’s a fight to the death for anyone not prepared to flee,” she said. “As a nation we refuse to flee. But we also refuse to die.”

Reviving canoe culture, Heine and others believe, could help Pacific Islanders navigate the rough waters ahead. The boats reduce the islands’ dependence on ships fueled by imported fossil fuels, and they serve as an important tool when disaster strikes, helping people move more nimbly, be it to flee storms or aid neighbors in need. Similar efforts are underway in other parts of the world, including the Pacific Northwest, where the Quinault Indian Nation, the Heiltsuk Nation, and others are combining cultural revival with climate resilience.

Heine has called for adding vakas to each of her country’s 24 island communities, which could operate like an inter-island ferry service. Marshall Islands and four other nations — Palau, Kiribati, Nauru, and the Federated States of Micronesia — are seeking nearly $50 million from the U.N.’s Green Climate Fund, to build what they call “indigenous community resilience” through vaka networks in Micronesia.

Each vaka motu can hold up to three tons of cargo, or a dozen passengers. By building vessels, enlisting sailors, and producing biodiesel from coconuts, advocates also aim to develop local economies, particularly in areas reliant on subsistence farming and fishing. (Okeanos, a partner on the funding proposal, says its founder, Dieter Paulmann, has spent $25 million since 2006 to build and operate vakas, train crews, and do community outreach.)

Natalia Tsoukala

Vakas alone can’t replace the trans-ocean freighters that haul thousands of tons of cargo across the world every day — to do that, we’ll need other sustainable shipping solutions. However, canoes are still an important piece of a more resilient future for these isolated communities, says watch captain Iva Nancy Vunikura.

Iva Nancy Vunikura, Okeanos watch captain, age 37

“In 2011, I hopped into a canoe and learned the ropes as I sailed. It was supposed to be a six-month journey, but turned into eight years. I got to connect back to my roots. Now I’m sharing what I’ve learned along the way.

“Anybody that comes on the vaka, we teach them how we look after the canoes, how we look after the people, how we work with the communities. This knowledge needs to be unlocked, as it has laid dormant for too long.

“Before, I didn’t know much about my own culture. Now I can tell you stories of our forefathers. I belong to a proud family of traditional voyagers from the Pacific.” Jess Charlton

She recalled how in 2015, in the wake of Cyclone Pam, she and other sailors, including Patai, delivered emergency supplies of food, water, and medicine to the outer islands of Vanuatu. They brought root cuttings of tapioca and kumura (sweet potato) so people could replant crops and rely less on imported, packaged foods. The vakas shuttled supplies for months as damaged diesel ships underwent repairs.

“We might be small, but we’re doing something that contributes to how we live,” Vunikura said from her home in Fiji.

Vunikura, a former rugby player for the national women’s team, sailed for the first time in 2011. She worked on Okeanos’ 72-foot vaka called Uto Ni Yalo (“Heart of the Spirit,” in Fijian), touring 15 Pacific nations to promote sailing culture and ocean conservation. She has since logged over 60,000 miles on traditional sailing canoes, and now works with adults and children across the region.

Recently, she spent five months training a dozen men in Yap, where she says women don’t traditionally sail. The Okeanos team had to first secure permission from a chief so Vunikura could participate.

“We can’t just come in and say ‘I want to do this.’ We need to respect the custom and culture,” she said. “It was hard for me. But they accepted it … and so I broke the barrier, you know? We need to be working as one.”

Anthony Tareg

Among the biggest challenges to building a pan-Pacific vaka network is navigating cultural differences among Polynesian, Micronesian, and Melanesian communities, Patai said. “You have to find out how people think,” he noted. Another difficulty is getting people to work on the vakas long-term, rather than treating it only as a hobby.

Steven Tawake, operations coordinator, Okeanos Marshall Islands, age 33

“Growing up, our elders would tell us things like, when the spiderwebs are very low to the ground, it means strong winds are coming. Or when the ants are taking food to the trees, it indicates heavy rain is coming. When I started sailing in 2009, I recalled what our elders told us, and said, ‘Oh, this is all part of navigation.’ Sharing the knowledge of sailing and navigation — especially when we teach young ones — is something that will keep our heritage alive.

“In 2017, I was sailing a canoe [to Saipan] from Yap, about 600 miles away. I encountered very strong winds, and I was struggling with my crew. I reached Saipan, and an old lady from the Caroline Islands called me. In the Carolinians, the women are the keepers of navigation knowledge. She sat down beside me, and she started singing chants to me. Other ladies came, and I was in the middle of them. It was something lovely.” Okeanos

For the Okeanos crew, there may be ample opportunity to sail in the coming year. In the Federated States of Micronesia, the health department in Pohnpei has signed a contract for 100 days of sailing charters to bring doctors, medical personnel, and sick patients between the main island and six outer islands. In the Marshall Islands, the government is providing an annual subsidy to partially cover the costs of crews, insurance, and maintenance of the vakas there. Late last month, an Okeanos team helped nurses carry out tuberculosis screenings in remote island communities.

Vunikura said she doesn’t know exactly what her 2020 plans entail. But she’ll undoubtedly be climbing aboard a vaka and promoting sustainable sea transportation in the Pacific.

“This is what I do for a living,” she said. “Somebody asked me, ‘What action would you do towards climate change?’ I just simply pointed at the canoe and said, ‘I’m living my action by sailing this canoe on our oceans.’”