This story is part of Fix’s What’s Next Issue, which looks ahead to the ideas and innovations that will shape the climate conversation in 2022, and asks what it means to have hope now. Check out the full issue here.

The nation’s conservation movement often gets traced back to 19th-century naturalists like John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and Henry David Thoreau — white men who favored protecting nature from human interference. Their work contributed to the creation of the first national parks, the U.S. Forest Service, and many policy legacies that persist today. But their exaltation of “pristine wilderness” is now seen by many as fundamentally racist, because it ignores, and in some cases erases, the fact that the First Peoples of this continent managed ecosystems for thousands of years before white settlers arrived. And, much like development, the conservation that they espoused often led to the seizure of Indigenous lands.

That racist legacy endures and has influenced conservation in other parts of the world. “For so long Indigenous stewardship really wasn’t recognized,” says Beth Rose Middleton, a professor of Native American Studies at the University of California, Davis. “People didn’t want to acknowledge the fact that humans have played a role in landscape stewardship since time immemorial, and that humans and landscapes have co-evolved.”

[Read: What is the Indigenous landback movement?]

That’s beginning to change amid growing awareness of Indigenous justice and the crucial role Native peoples play in protecting natural resources. Research in 2018 revealed that Indigenous people make up less than 5 percent of the world’s population but support 80 percent of its biodiversity. The Standing Rock movement of 2016 and 2017 illuminated the fact that Indigenous land and water protectors have long led resistance to fossil fuel projects. Land acknowledgements — statements or plaques that recognize the tribes whose land we stand on — have become common practice at universities and cultural institutions like museums, as well as in cities like Denver; Portland, Oregon; and Tempe, Arizona. As recognition of the original stewards of this continent has grown, so too has recognition of a longstanding movement to give that land back.

Simply put, landback is a reparations movement that has existed since colonization. Its goal is the physical return of land to Indigenous peoples — and the return of all things that depend on connection to the land. “We were fully thriving economies and societies and communities pre-colonization,” says Krystal Two Bulls, director of the landback campaign launched a little over a year ago by the Indigenous advocacy organization NDN Collective. “We had trade networks, we had food and housing, education, healthcare. We had kinship, we had governance models, our languages, our ceremonies, our culture.”

NDN Collective’s campaign is a centralized effort to coordinate, amplify, and provide resources for landback initiatives throughout Turtle Island, though Two Bulls notes that landback is a global concept that no one owns. The pillar of the campaign is a battle to close Mount Rushmore and return the Black Hills to the stewardship of local tribes — a move that advocates believe would galvanize the broader movement. Symbols are important in any movement, and Mount Rushmore, with the faces of colonizers and slaveholders carved into a mountain that tribes consider sacred, is nothing short of symbolic.

[Read: How Indigenous leaders are reclaiming and spreading cultural knowledge]

“When we get our Black Hills back and when we shut down Mount Rushmore, that changes what is possible for Indigenous peoples globally. That changes what is possible for all peoples who are fighting to dismantle white supremacy,” says Two Bulls.

“We are getting more organized now than we’ve ever been in history,” says Nick Tilsen, the president and CEO of NDN Collective, and a 2019 Grist 50 honoree. “I think that landback was less of a conversation a year and a half ago, and I think that we played a fundamental role in putting it center stage,” he says.

The Black Hills — Paha Sapa in Lakota — is the geographical heart of the United States and also the site of one of the nation’s oldest land disputes. The federal government granted the land to the Sioux under the Fort Laramie Treaty in 1868 as part of their reservation, “set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation of the Indians.” (“Sioux” is a French misnomer that refers to the Oceti Sakowin, a group of tribes in the plains region of North America.) But the discovery of gold in the 1870s led the U.S. Army to move in, along with miners. This sparked The Great Sioux War of 1876 — a conflict that included the famed Battle of Little Bighorn — and the government’s confiscation of the land in 1877.

Still, the fight over the Black Hills continued and eventually reached the Supreme Court, which ruled in 1980 that the seizure constituted a gross violation of the U.S. Constitution. “Yet they didn’t return lands back to our people,” Tilsen, a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation, says. Instead, the court awarded $105 million to compensate the Sioux for the land. That award has now matured to over $1 billion — because the tribes have refused to accept it. “The Sioux tribes have always maintained that that confiscation is illegal and that the tribes must have some of their ancestral lands returned to them,” tribal attorney Mario Gonzalez said in an interview with PBS in 2011. If the money were accepted, it would amount to accepting the broken treaty — and, if the sum were to be distributed to the thousands of Sioux people who have a claim to the Black Hills, it would be gone within years or even months.

Instead, multiple approaches have been tried over the years to negotiate the land’s return. In 1985, U.S. Senator Bill Bradley of New Jersey introduced an unsuccessful bill that would have transferred 1.3 million acres of forest in the Black Hills to the Great Sioux Nation. More than two decades later, advocates hoped President Obama would return the land through an executive order, after his campaign suggested he was open to “government-to-government negotiations to explore innovative solutions to this long-standing issue.”

Today, NDN Collective is trying another approach: coordinating with 16 tribes to establish the Oceti Sakowin Nation Land Trust, which would work with the Department of the Interior to co-manage the land. Tilsen expects the land trust to be formed within the next year, as a type of tribally owned, tax-exempt corporation with the same sovereign rights that tribes hold. “That will be a mechanism to get our people back on lands that we have been removed from,” Tilsen says, “working the land, building back that connection between the land and the people, building our capacity to manage lands in the first place.”

“Your fear is rooted in the fact that you think, when we get our land back, we will treat you the way that you have treated us.”

—Krystal Two Bulls, director of the landback campaign at NDN Collective

A total of 574 federally recognized tribes currently manage around 56 million acres of reservation land throughout the U.S. — though that land isn’t always on a tribe’s original homelands and is often on the least livable, least economically valuable fringes.

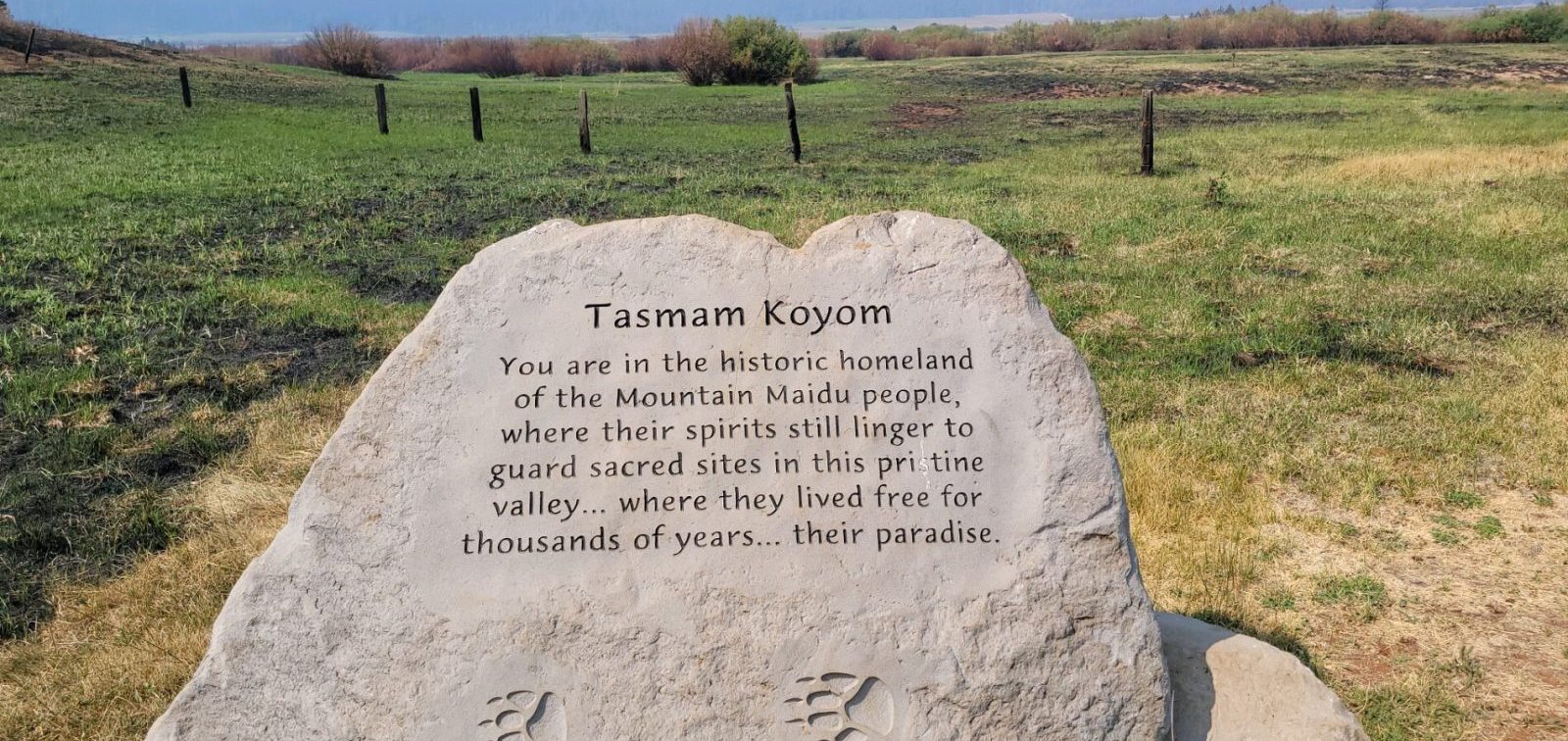

For tribes without federal recognition, it’s extremely rare and difficult to hold land at all. That was the circumstance facing the Mountain Maidu people in Northern California, who historically lived in the higher elevations of the Sierra Nevada mountains. “We were never allowed a process of having our own land base,” says Allen Lowry, a board member of the nonprofit Maidu Summit Consortium. “It just didn’t happen, because of the gold and the mining and the timber and all of these things.” But for generations, Maidu people in California retained a connection to their lands and sacred sites.

In 2003, Pacific Gas and Electric Company — one of the largest landholders in traditional Maidu territory — agreed to a deal California officials and environmental groups brokered to sign over some of the company’s land to various conservation easements in exchange for a bankruptcy bailout. The Maidu Summit Consortium was formed that year as a legal entity to represent the tribe and provide a vehicle for negotiations for the return of their land.

“The Maidu people from all of our different valleys and ancient village sites and territories were all welcome,” Lowry says. “A lot of them came together, for really one of the first times, with one thing that we could all agree on: to protect our land. We wanted a voice, which we never had.”

It took another 16 years before the first parcel of land was returned. But today, the organization stewards nearly 3,000 acres of traditional Maidu lands, including a public campground. If visitors are interested, they can learn more from the camp’s new managers about Maidu history and culture. The consortium is still finalizing transfer of the final parcel, but with the lands that have been returned to date, it has started fencing around sensitive habitats and plans to reintroduce native plants.

“It was just an all-out battle to get to this point,” says Trina Cunningham, the organization’s executive director. “That transition from [focusing on] that into actually being stewards of our own landscapes again is pretty tremendous.” The consortium is now pivoting to determining its own priorities for the land, and building the capacity to take on those management and restoration projects. The most immediate goal will be studying and recovering from the Dixie Fire, which burned hundreds of acres of the newly returned land last summer.

Restoring knowledge and relationships with traditional lands is something the leaders in the Black Hills also hope to accomplish — which is one reason why co-management with the federal government makes sense as a first step toward sovereignty.

“I see very clearly that we have a unique opportunity right now,” Two Bulls says. With Deb Haaland as the first Indigenous secretary of the interior and appointees like Chuck Sams, the first Native American to lead the National Park Service, Two Bulls and others feel a great urgency in pushing forward landback initiatives before the next presidential election. Just last month, the Interior Department resolved a decades-long fight by the Mashpee Wampanoag, the famed Thanksgiving tribe in New England that the federal government did not recognize until 2007. The ruling gives the tribe control over some 320 acres that had been placed in federal trust by President Obama and subsequently threatened by President Trump. Although it represents just 0.5 percent of their original territory, its return will create revenue and stewardship possibilities for the tribe.

One of the challenges with the landback movement, Tilsen says, is that it’s a narrative that makes people fearful. As Corbin Herman, the former mayor of Custer, South Dakota, told The Guardian, “This whole country is on Indigenous territory, so where does returning land start and where does it end?” But landback is about more than ownership, a word some in the movement find troublesome. It means dismantling white supremacy and challenging not just how natural resources are managed but who has decision-making power over land.

“I think a lot of what we’re talking about with landback is, why are these lands being held in these institutions where they’re apart from stewardship?” Middleton says. “These are places people are still caring for, singing about, talking about, places that are embedded in language.”

Tilsen believes that landback will lead to more fossil fuels being kept in the ground and a fusion of Western science with traditional ecological knowledge that will actually keep so-called wilderness pristine. “At first people are going to be like, ‘Oh, my God, the Indians are getting their land back — run for the hills, everybody!’” he says. “And then they’re going to be like, ‘Oh, my God, they’re doing a pretty good job.’”

Two Bulls says she can drink water directly from springs on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in Montana, where she lives. Despite mining and fracking in the surrounding areas, Northern Cheyenne has maintained some of the highest air and water quality standards in the nation, she says, because it’s not a “checkerboard reservation” but rather 99 percent Cheyenne-owned.

“When we fight pipelines, when we fight oil projects, when we fight all of the extractive development that harms our mother, we don’t do that just for ourselves,” Two Bulls says. “We do that so we can all actually have an earth to live on in the future. So that future generations that aren’t even born yet have an earth to come to.” Ultimately, she believes that opposition to landback and what it will mean for the descendants of settlers comes from a place of guilt. “Your fear is rooted in the fact that you think, when we get our land back, we will treat you the way that you have treated us.”

Replicating systems of oppression has never been part of the plan, and proponents of the movement say they could use some help from white people in dispelling that knee-jerk fear and explaining why this solution will benefit everyone. “A lot of our allies and accomplices could play a really important role in helping lead some of those conversations,” Tilsen says, “so that we, as Indigenous people, can focus on getting our damn land back.”

Explore more from Fix’s What’s Next Issue:

- What Biden’s ‘smart’ border means for climate migration

- Hope is not passive: How activism keeps optimism alive

- Pop culture can no longer ignore our climate reality