This story is part of Fix’s Outdoors Issue, which explores how we build connections to nature, why those connections matter, and how equitable access to outside spaces is a vital climate solution.

“In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” So begins The Repair, the fifth season of the podcast Scene on Radio. It asks, in a nutshell, where the West went wrong and became such a destructive, extractive society. Between clips of news reports describing wildfires, floods, and extinctions, hosts Amy Westervelt and John Biewen read from Genesis 1, recounting God’s creation of the first humans in his image: “God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it; and rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky, and over every living thing that moves on the earth.’”

By opening with these Bible verses, Westervelt and Biewen suggest that Judeo-Christian thought is a major contributor to our climate emergency.

They are far from the only people who feel this way. Such beliefs date to at least the 1960s and the start of the environmental movement. Historian Lynn White argued in 1967 that the roots of our ecological crisis are religious; he traced the problem to the first chapter of Genesis and the idea of dominion contained in verses 26 and 27. They often are understood to mean that humans are separate from, and superior to, nature, which exists solely to serve them. Over the centuries, European Christians have interpreted other passages (such as the idea of a promised land and Jesus’s command to “make disciples of all nations”) to justify appropriating and extracting resources and oppressing Native populations.

But this isn’t the only way to interpret the Bible. The First Nations Version, published in September 2021, presents the New Testament through the cultural sensibilities of the Indigenous peoples of North America. Its prologue sums up the creation story this way: “Creator made the first man and woman and placed them in the Garden of Beauty and Harmony to be caretakers of the earth.”

Such changes infuse the translation. Instead of “subdue,” we get “care.” Instead of “God,” we get “Creator.” Instead of “prayer,” we get “dance upon the earth for the things you seek” (Matthew 6:7). These subtle shifts embed Native understandings of the human–earth relationship into scriptures that too often have been used to justify exploitation and conquest. [Ed note: The publisher of the First Nations Version, InterVarsity Press, also published a book by the author of this article.]

Those behind the translation say they are not radically remaking the New Testament. Rather, some Indigenous Christians believe that the interdependent, relational view of humans and nature suggested in the First Nations Version is deeply embedded in scripture but has been lost as the biblical story was filtered through Western cultural perspectives. Today, even non-Native Christians have many varied interpretations, including ones closer to Indigenous readings. Combined with the surprising popularity of this translation — which has, according to its publisher, been welcomed by non-Natives and sold out its first printing within weeks — such a view could reshape Christian understanding and stewardship of the natural world by placing humans within, rather than above, creation.

“The way we behave affects the way creation responds to us,” says lead translator Terry Wildman. “There is a reciprocal aspect to our relationship to all of creation, and scriptures bring that out.”

* * *

This is not the first translation by and for Indigenous people; parts of the Bible have been translated into a range of First Nations languages. But 90 percent of Native peoples in North America don’t read or speak their tribal language, Wildman says, and this is the first English version to present scripture from an Indigenous perspective.

That said, the First Nations Version isn’t intended to address climate issues. Wildman, a pastor and musician with Yaqui and Ojibwe ancestry, got the idea for the project about 20 years ago while working on a Hopi reservation in Arizona. He was excited to find a Hopi translation of the New Testament, but couldn’t find anyone capable of reading it. Wildman thought he’d try his hand rewording passages in English, in ways Native people would find meaningful.

Wildman kept working on various parts of the Bible until 2015, when the Bible translation group OneBook Canada offered to fund a translation of the New Testament. Working with a council of 11 other Indigenous Christians representing at least 15 North American tribes, Wildman strove to capture the oral storytelling cadences of a tribal elder to convey scripture in a way that didn’t immediately raise barriers for Native readers.

Given the history of missionaries and boarding schools forcing the Christian faith onto many Native people, Wildman wanted to avoid words that might trigger painful memories or associations. Evangelists, for example, used words like “sin” and “kingdom” to strip Indigenous people of their cultures and identities in their quest to assimilate them. “It was a sin for us to have long hair. It was a sin to speak our language,” Wildman says.

“I have to separate the colonial Jesus from the real Jesus,” he adds.

The First Nations Version conveys the deep resonance Wildman and other Indigenous Christians feel between Native perspectives and the teachings of Jesus Christ. “The more that I have studied our own people, the more I see that our whole system is Christlike,” says Adrian Jacobs, Keeper of the Circle at the Sandy-Salteaux Indigenous ministry training center for the United Church of Canada in Manitoba, Canada. “Christ gave his life for us to live. The spirit of our [Haudenosaunee] creation story and Thanksgiving address is all about how creation lays down its life so that others could live.”

[Read: How the Indigenous landback movement is poised to change conservation.]

While the opening chapters of Genesis often are understood as separating humans from nature, other parts of scripture clearly affirm nature’s own relationship with God, says Danny Zacharias, an assistant professor of New Testament studies at Acadia Divinity College. Zacharias, who is of Cree and Anishinaabe descent on his mother’s side, says books like Job and the Psalms state that God breathes life into other created things beyond humans.

“He commands them, talks with them, and gives them roles,” Zacharias says. “They’re not just objects.” The first two lines of Psalm 19, for instance, read “The heavens declare the glory of God, the skies proclaim the works of his hands. Day after day they pour forth speech; night after night they reveal knowledge.” (The Psalms are next on Wildman’s list for translation, along with Proverbs and Genesis. They are books in the Old Testament, the portion of the Bible that chronicles ancient Isrealite interactions with the God of Abraham from creation until about 400 years before Christ’s birth.)

If objectifying nature led Western societies down the road toward global climate crisis, then healing might come through articulating the interdependencies between humans and nature. The First Nations Version takes small steps toward this by emphasizing those relationships. For example, Matthew 5:5 is commonly translated as “Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.” That line becomes much more poignant in this new translation, which reads, “Creator’s blessing rests on the ones who walk softly and in a humble manner. The earth, land, and sky will welcome them and always be their home.”

That difference appears subtle, but it shifts agency from people, who do the inheriting, to the earth, land, and sky, which does the welcoming. For Zacharias, these language shifts matter. “They imply relationships between things, as opposed to objects that sit on their own,” he says.

The First Nations Version further captures the relationship between humanity and the natural world by translating names into their active meanings. Jesus is called Creator Sets Free. Peter is Stands on the Rock. Moses is Drawn from the Water. These changes are important, Zacharias says, because they show “you’re defined by your relationship to other things.” The kingdom of God is translated as “Creator’s good road.” “It’s not a place somewhere, but a way of life,” Wildman says. “On Creator’s good road, everything is related. When Natives talk about ‘all my relatives,’ they’re talking about the animals, people, the earth, the rivers.”

Zacharias often calls the earth “mother” when he speaks, to the dismay of many non-Native Christians not used to hearing such language. “I always get so many questions and have to point out that maternal language for creation is actually in Romans 8,” he says. “Is it really that surprising? What would it do if you started thinking about creation in that way? Hopefully our actions will flow from the way we speak and think.”

If objectifying nature led Western societies down the road toward global climate crisis, then healing might come through articulating the interdependencies between humans and nature.

Some Christians believe the Bible always contained these meanings. But when early followers of Jesus ventured beyond Israel, some of the relationships embedded in scripture were lost as they translated their message from Hebrew and Aramaic, two verb-based languages, into Greek and, later, the Romance languages, which are noun-based. The dynamic implications of Jesus’s name as Creator Sets Free, for instance, get lost in a static, stand-alone proper noun.

For Mark Charles, an activist and pastor of Navajo and Dutch descent, this loss of relationship-based understanding is apparent in the way Western Christians handle the biblical creation story. “Creation stories are very context-specific. They help you understand your relationship with your creator and your surroundings,” Charles says. The Genesis story, for instance, mentions the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in modern-day Iraq. Indigenous stories often explain the origins of Turtle Island, or what is now known as North America. Western Christians, Charles said, often feel strong attachment to lands mentioned in the Bible because they’ve lost, or never had, spiritual connection to the lands on which they reside.

* * *

Despite being written by and for Native people, not all Native readers appreciate the translation, or feel it is needed. “It sounds gimmicky,” says Fern Cloud, a member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate tribe who leads the Dakota Presbytery of the Presbyterian Church U.S.A. (Her group has read portions of the translation.) “Jesus is Jesus. He was in the Hebrew culture. We understand that. Don’t try to make him Indian.”

Critiques from people like Cloud, whose congregations use a Bible translated into their tribal language, are part of an ongoing conversation among Native Christians about whether, and how, it is appropriate to blend traditional spiritual elements with Christian practice. In the 1980s, Indigenous Christians who reclaimed their tribal heritages as God-given kicked off what became known as the Native contextualization movement. It asserts that God, or Creator, has been with Native peoples all along.

“Our elders understood that Christ had been with them already before the Europeans came,” says Ray Aldred, a member of the Cree Swan River Band, Treaty 8, who teaches at the Vancouver School of Theology. For example, he says, the Nisga’a people in modern-day British Columbia recognize that “Christ is here among us in our law, which comes from Creator, who gives it to us through creation.”

For tribes using Bibles translated into their languages, these connections between land and faith are clear. One Canadian tribe translated the word “sea” in Psalm 95:5 (“The sea is his for he made it”) as their word for Lake Winnipeg, notes Aldred. In the Cree bible, the word “world” in John 3:16 (“For God so loved the world that he gave his only son…”) is translated as “askiy,” meaning land. “For God so loved the land…” has a markedly different feel.

According to Aldred, every translation has its pros and cons. A potential drawback of the First Nations Version, Aldred points out, is that it might reify various phrases “and get it into non-Indigenous people’s minds that this is the way we talk.”

With sales nearly tripling what the publisher expected, the popularity of the First Nations Version beyond its original audience of Native readers signals growing interest in Indigenous perspectives among North American Christians. But Randy Woodley, a Cherokee descendant who teaches at Portland Seminary, worries that it may be a fad.

“It used to be, ‘Oh, I have Native friends’ or, ‘I have Native objects in my home,’” Woodley says. “Reading an Indigenous paraphrase is not going to change people’s worldview. We need a drastic change, and we need it fairly quickly. I don’t think substituting names is going to make a lot of difference. We need to substitute theologies.” Woodley advocates for giving the earth human rights, while others bring up honoring the original treaties or returning land sovereignty to tribes.

The First Nations Version may not get all readers on board with that vision, but its fresh language could jolt non-Natives to reassess their responsibilities and relationship to the natural world, especially as human-induced climate change threatens fragile ecological balances. As Charles sees it, Western Christianity has co-opted and misused the creation story in the Bible because it lost touch with its own land-based roots and creation stories.

“By referring over and over again to Creator — and to Jesus as Creator Sets Free — the First Nations bible reminds Western Christians, ‘There’s something you’re missing, something you’ve forgotten that is incredibly central,’” Charles says. That missing piece, he and others argue, is a place-based, land-based spirituality. “This bible reminds our uninvited guests of who Creator is,” Charles says, adding that the entire trajectory of the Bible is about restoring relationships. “This not only includes being on friendly terms with God again, but is dependent upon walking in beauty, as my Navajo people would say, within the land.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misidentified the Church of Canada as the Church of Christ. This post has been updated.

Some reporting for this story was made possible by a grant from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.

Explore more from Fix’s Outdoors Issue:

- Finding strength, and a calling, in a brood of eaglets

- Foraging New York City’s wild, edible margins with Journei Bimwala

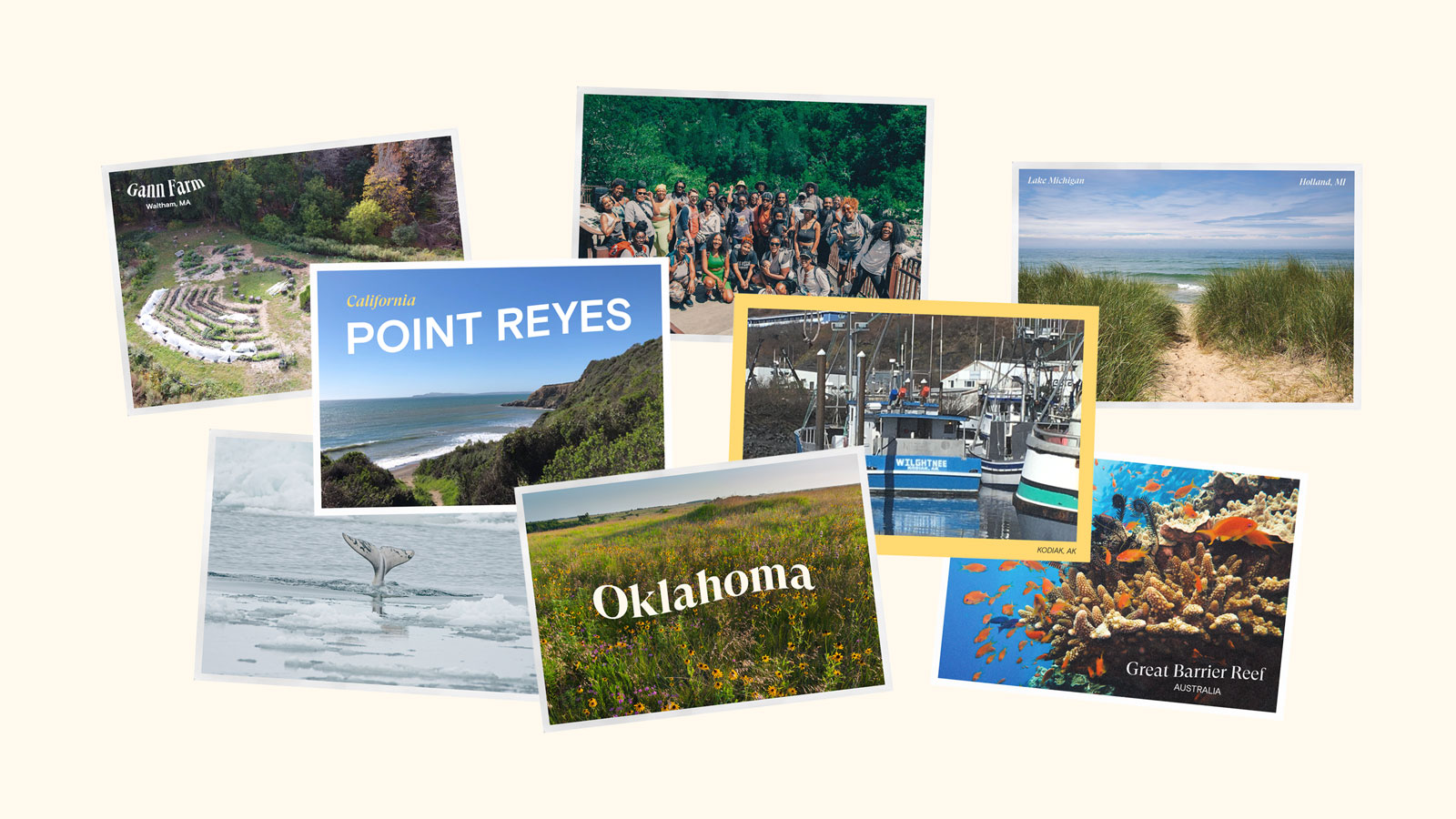

- How outdoor experiences have shaped today’s climate and justice leaders