The vision

You sigh at the empty bottles forgotten on your kitchen counter. Your partner was supposed to stop by the refillery after work. You’re about to send a grumpy text when …

Ugh, is all they type.

DON’T buy more bottles, you write. You’ve got bottles galore, all you need is shampoo.

Let’s just go together tomorrow? We need to go food shopping too, we can hit both places. You’re annoyed, but at least now you get to go to the refillery — a favorite weekend stop. You start listing the other things that could use refilling: lotion, toothpaste, sunscreen …

— a drabble by Claire Elise Thompson

The spotlight

You’re probably familiar with the scourge of plastic waste. At the end of its useful life, plastic becomes a nuisance, or even a danger, to marine ecosystems, city infrastructure, and our own bodies. But plastic is also an environmental disaster at the start of its life. Over 99 percent of plastic is produced from chemicals derived from fossil fuels, and the two industries are closely tied. According to the Center for International Environmental Law, the natural gas boom in the United States is driving a ramp up in plastic production, which increases pollution risk to frontline communities and directly counters cities’ efforts to ebb the flow of single-use plastics.

If that’s not sobering enough, according to a new report, greenhouse gas emissions from the plastics industry are on track to surpass coal by the end of this decade.

As we’re preparing for the consumption-centric holiday season, the time is ripe to consider how we can cut back on plastic and its associated emissions. And it’s not all about giving stuff up, although consuming less is certainly good for lightening our footprint on the planet. In this newsletter we’re spotlighting three other emerging solutions moving us toward a less plasticky future.

Creating a refill culture

In 2011, José Manuel Moller was living with some of his university classmates in a low-income neighborhood in Santiago, Chile. On his limited student budget, he was continually buying the smallest sizes of everything — “a quarter-liter of coconut oil, a quarter-kilo of sugar,” he recalls — each in its own throwaway container. After a while, comparing notes with his mom, he realized that he was spending much more than she was on household items. That’s because the smaller sizes, which have a higher packaging-to-product ratio, cost more per ounce. The packaging itself can make up as much as 40 percent of the cost, creating a poverty tax for those who can’t afford to invest in more efficient bulk options.

“It’s absurd that we’re pushing the poorest families to pay for something that they’re going to throw away, that’s also polluting the planet,” Moller says.

With a background in business administration and funding from some local contests, Moller designed a company called Algramo — a tech-enabled refill system that dispenses food and cleaning staples in bulk. The company has over 2,500 stations in Chile, and pilots in New York City and Jakarta, Indonesia. The BYORP (bring your own reusable packaging) model opens up economies of scale to customers at all income levels.

Here’s how it works: The Algramo containers look like standard bottles of Softsoap, Pine-sol, or what have you, and contain the same info, like the ingredient list. But they come with RFID-enabled chips that sync up to an app. You can add money to your account through the app, which then gets transmitted to the chip — making the container itself a kind of wallet. As Moller points out, you may forget to bring your reusable shopping bags to the store on occasion; you never forget your wallet. [Read more about Moller and Algramo in this feature.]

Algramo is far from the only company trying out a high-tech approach to to the refill economy. Refilleries are popping up all over — there may already be one near you. But if you bring your own bags to the grocery store, your own thermos to Starbucks, or your own water bottle to the … wherever, then congrats! You’re already part of the refill revolution. Next stop: everything.

Recycling and upcycling

Currently, less than 10 percent of virgin plastic actually gets recycled in the U.S. The vast majority winds up in landfills. And what does get recycled is more commonly “downcycled” — instead of becoming another soda bottle, for example, plastic often goes to composite products, such as faux wood or carpeting, from which it can’t be recycled again.

This is a problem that scientists and engineers have turned their attention to — including a group of labs that make up the BOTTLE consortium (Bio-Optimized Technologies to keep Thermoplastics out of Landfills and the Environment), a multi-organization research partnership supported by the U.S. Department of Energy. And one particularly neat area of exploration is plastic-eating organisms.

There are more than 50 species of known plastivores, including bacteria, fungi, and a caterpillar known as the wax worm. Not only can these critters digest plastic, with a couple of extra chemical steps, they may actually be able to turn it into something better. In a study published earlier this year, scientists from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Colorado demonstrated a process through which the common soil bacteria Pseudomonas putida can can help to “upcycle” polyethylene terephthalate (PET, the most common type of polyester) into a replacement for nylon (a type of silklike plastic with many applications beyond pantyhose).

Biologist Alli Werner, the lead author of the study, and her team used a chemical process to break down PET into its component parts. They then fed those building blocks to specially engineered bacteria, which excreted a compound called β-ketoadipic acid that can be used to make a type of nylon superior to what’s widely used today.

“This is the idea behind plastics upcycling,” says Werner, “turning waste into higher-value materials so that reclaiming plastics can be profitable.” [Read more about plastivores in this feature, and in this work of fiction from Imagine 2200, Fix’s short-story contest.]

Replacing plastic at the source

OK, we’ve covered reuse and recycle. But one of the best things we can do to keep plastic out of our water and emissions out of our lungs is reduce how much of it we make and consume in the first place. That may not be possible in every instance, but plenty of companies are sprouting up to offer alternatives to common plastic products. One such company is Fortuna Cools, which makes a coconut-fiber cooler designed to displace one of the most hated plastics of all: styrofoam.

The company started out as a class project in the Stanford d.school’s Design for Extreme Affordability course. Tamara Mekler and her classmate (who became cofounders) were partnered with Rare, a conservation org in the Philippines. Their challenge was to improve the livelihoods of fisherfolk.

“At the design school, they always tell you, ‘Look for the duct tape,’” Mekler says — meaning the small fixes that people are using to make something last a bit longer, or make something more convenient, that better design could solve in a more permanent way. But what they saw in the Philippines was literal duct tape. Fishers were using it to hold together scores of styrofoam coolers once they started to break apart.

And duct tape doesn’t last forever. “Food suppliers have to replace their entire styrofoam inventory approximately every month,” Mekler says. That adds up to a big cost for the workers, and the environment.

She and her team started looking for locally available materials that could help the workers save money and produce less styrofoam waste. They found their answer on coconut farms, which are everywhere in the Philippines, and which have a waste stream of their own: husks. Piles and piles of coconut husks were being burned by farms that didn’t have an immediate use for them.

“A lot of people have had the experience of drinking fresh water from a coconut,” Mekler says. “At least in my case, I’m always surprised and amazed that it’s so fresh and refreshing. It’s because coconut husk is a great insulator.” The group that became Fortuna Cools took that lesson from nature and designed a more durable and effective cooler made from coconut fiber insulation and 100 percent recycled polyester. Based on feedback from pilot customers, they were also able to make their cooler collapsible — something that helps reduce shipping costs when the coolers are empty.

“Pretty much all of these performance requirements that we look for in plastic materials have been solved one way or another in nature already,” Mekler says. She and her team are particularly excited about opportunities to utilize agricultural waste, which is a double win from the sustainability standpoint and also creates more income for farmers.

And Mekler’s work is just one example of the ways plastics are already being replaced with alternative materials out in the real world. Others are experimenting with algae or fungi that can create plasticlike materials. Meaning if you haven’t encountered plastic alternatives in your own life yet, you likely will soon. And they’ll be way more exciting than canvas grocery bags or (much-maligned) paper straws.

“There’s so much opportunity to be building better products, from a usability point of view, from a performance point of view,” Mekler says. “I think designers are being more creative about that, and understanding that there’s a lot of these technical abilities that we can get from materials that are not petroleum-based.”

More exposure

- Read: An in-depth breakdown of plastic and the ways in which it’s choking our environment, particularly marine ecosystems (Nat Geo)

- Read: A chronicle of the ups and downs of zero-waste businesses during a trash-filled pandemic (Grist)

- Read: A look at reusable packaging service Loop, which partners with beloved brands like Häagen-Dazs and Love Beauty and Planet to supply familiar products in new, returnable containers (Fast Company)

- Listen: The Circular Economy Podcast spotlights innovators (including the folks at Algramo) who are working on better business models for people, planet, and profit

- Watch: Some tips for eliminating single-use plastics from other areas of your life (@queerbrownvegan on IG)

- Explore: This multifaceted gift, travel, and eating guide for the 2021 holiday season (Grist)

See for yourself

How else do you remove plastics from your life? Reply to this email and let us know something you’ve tried to reduce your plastic footprint this holiday season (and beyond).

Something else on your mind?

We want to hear your vision. Email us about the game-changing solution you’re working on or a topic you’d like to see this newsletter cover — or try your hand at writing your own 100-word drabble. Tell us what you see in our climate future (and maybe you’ll see it in the future of this newsletter).

On our horizon

- Sneak peek: Listen now to the trailer for Season Two of Fix’s Temperature Check podcast. Next week we’ll be releasing the full season and our December digital magazine issue, which explore the theme of mentorship in the climate and justice movements. Stay tuned for more!

- Fix also has two live (virtual) events coming up: On December 2, join us and Elemental Excelerator for a conversation on investing in climate tech. This is part of our How We’re Fixin’ It event series, which showcases replicable and expandable climate solutions. Register here.

- On December 6, we’re continuing our exploration of mentorship with an evening of music, art, and live storytelling focused on tales of unlikely inspiration and life-altering relationships. Join Fix and Back Pocket Media for this unique event. Don’t miss it.

A parting shot

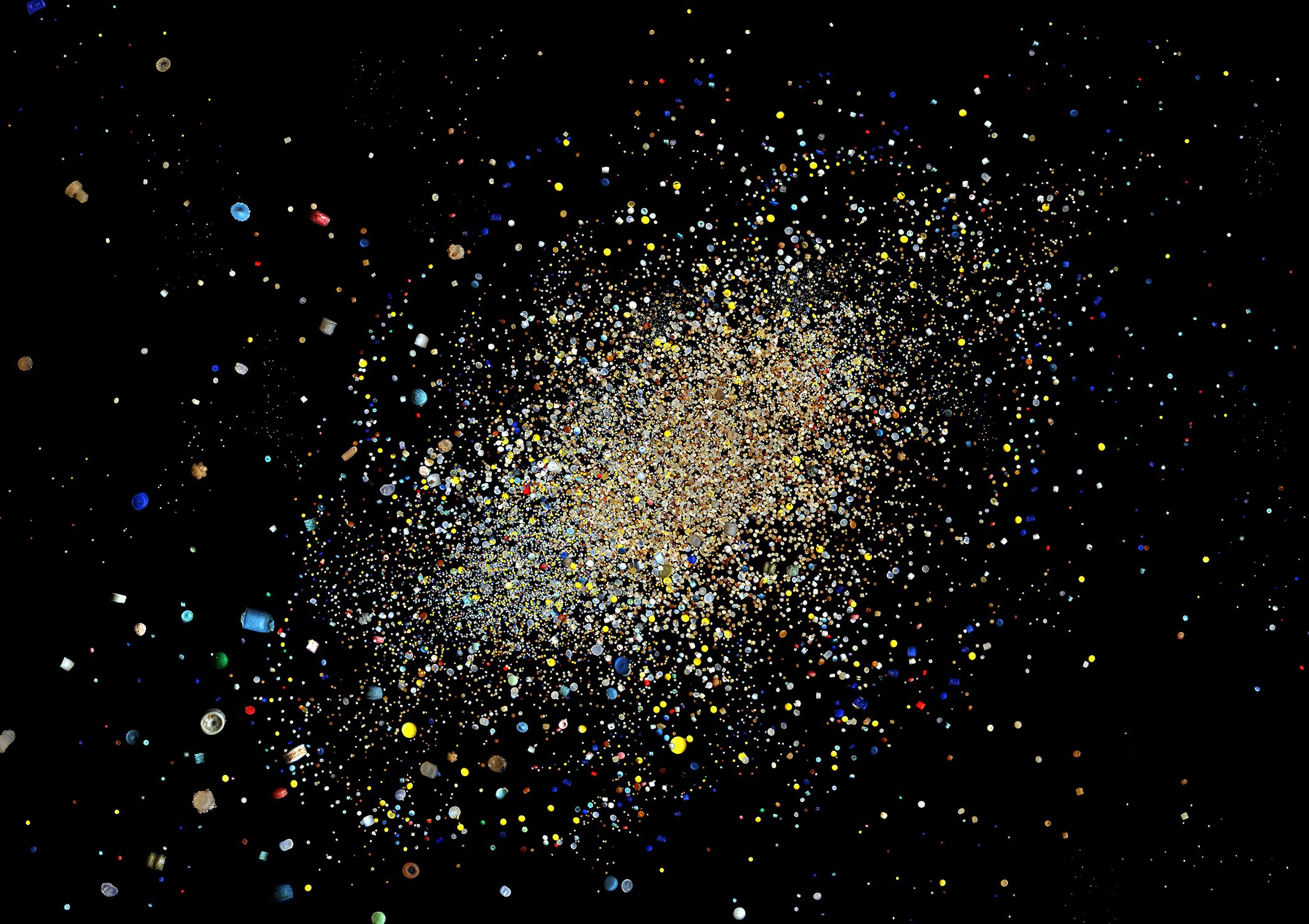

SOUP: Nurdles

This photo, from the SOUP collection by photographer Mandy Barker, shows a constellation of nurdle pellets — the industrial raw materials used to make many plastic products — collected from six beaches around the world. Nurdles are also commonly known as “mermaids’ tears.”