Long-suffering environmental activists cheered last month when an organized investor revolt forced ExxonMobil to add three climate-conscious directors to its corporate board. Despite nearly a generation of shareholder activism, nothing like it had ever happened. It seemed like a historic comeuppance for the petroleum powerhouse.

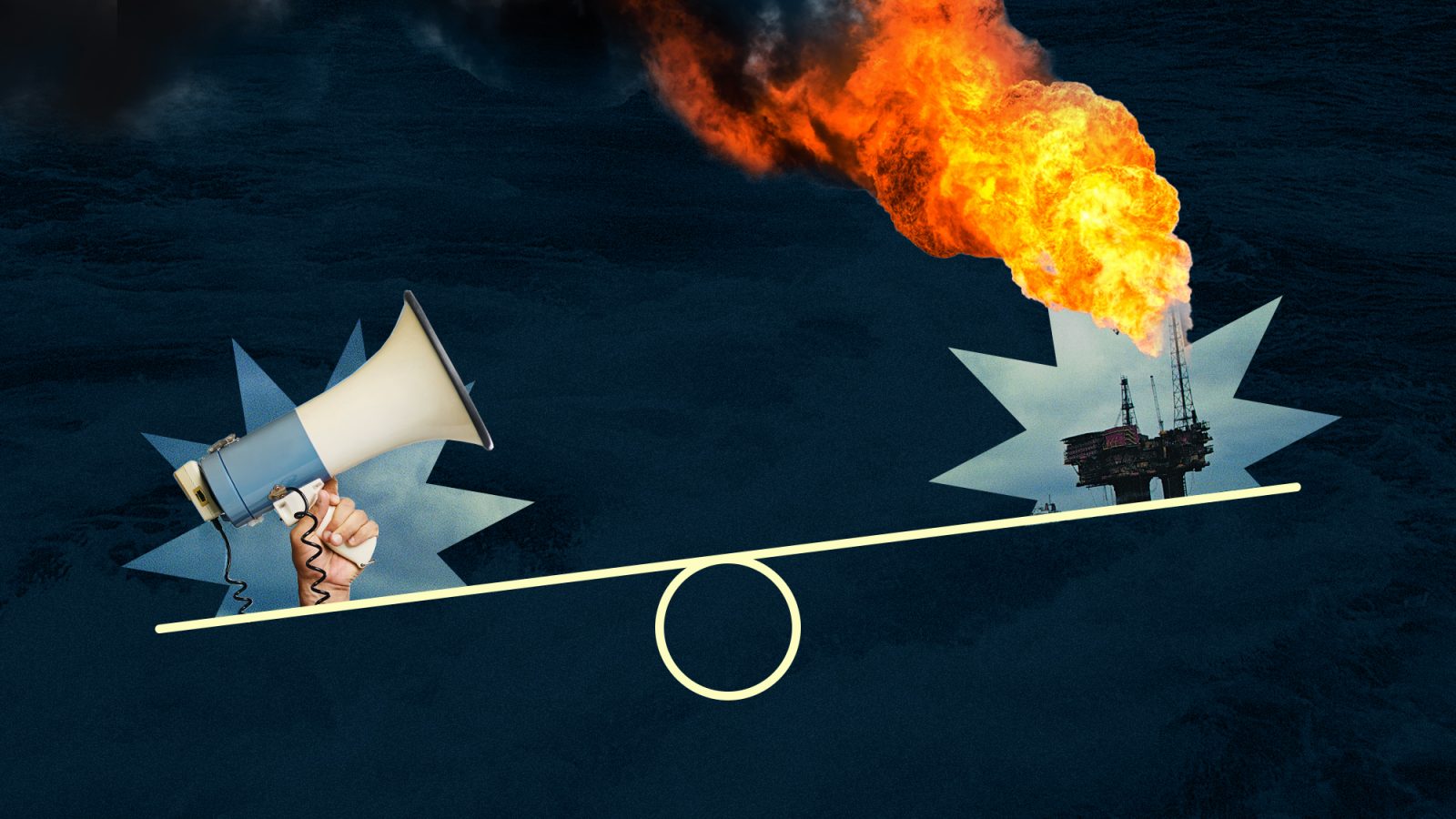

But those who pay close attention to the tension between fossil fuel companies and their investors offer a more nuanced take. Don’t expect the Exxon oil tanker to turn around overnight, they say. Instead, consider the move the beginning of a cultural shift, one of those fuzzy, hard-to-recognize but essential-in-retrospect moments when everything starts to change. In coming years, similar tactics could be leveraged against other stubborn, carbon-loving corporations. And, in a page from the Big Tobacco playbook, investors could join forces with legislators, plaintiff’s attorneys, and others to finally put the whole industry on its heels.

“It’s a real sign that investors are impatient, fed up,” says Kathy Mulvey of the Union of Concerned Scientists. “It’s a strong indication that there’s going to have to be substantive shifts in the company’s direction.”

What makes it more surprising is, among Big Bad Oil Companies, Exxon was once the Biggest and the Baddest. More than a decade ago, it was the largest public company in the world, with a reputation and a hefty dividend that made it a bedrock of many investment portfolios. More recently, as other oil giants pledged to reduce emissions or pivot to renewables, Exxon promised to drill, baby, drill, and planned to ramp up production of fossil fuels.

For a generation, activists of all stripes pushed the company to change, with little impact. But last December, a small San Francisco hedge fund called Engine No. 1 launched a public campaign to replace four corporate board members with directors who acknowledge climate change. Its motivation was money: Exxon’s returns are lagging, its debt is sky-high, and its value has crumbled. The company’s refusal to plan for a low-carbon world is just bad business, they say.

Exxon leadership fought back, and lost. At the company’s annual shareholder meeting, where such things are decided, on May 26, fund managers like BlackRock and massive investors like California’s state employee retirement fund voted with Engine No. 1. Three of the four rebel candidates were elected to the board.

The loss hit the carbon-spewing colossus where it hurts. It’s essentially a vote of no confidence in senior leadership by major investors. By pointing out Exxon’s poor economic performance — and linking that failure to the company’s recalcitrance on climate — Engine No. 1 revealed a weak spot in the oil and gas giant. Though the three new board members can easily be outvoted by the other nine directors, it will be difficult for executives to ignore these new voices.

Besides, the move seems to be part of a trend: During that same week, Chevron shareholders approved deeper cuts to greenhouse gas emissions, and Dutch Shell lost a major climate court case. It’s as if a door that had been sealed shut is now cracked open.

As Engine No. 1 founder Chris James told the Financial Times: “Our ambitions are clearly broader than Exxon.” Here’s what to watch for to see if change is truly coming — and what we might expect next.

Kathy Mulvey, climate accountability campaign director at the Union of Concerned Scientists

“This sent a message that reverberates more broadly, and certainly the other major oil and gas companies are taking note.”

I’ve been going to fossil fuel company shareholder meetings for the last five or six years. The annual meeting is the company’s turf. It’s their show. Anything that creates this much drama is exactly what they don’t want.

I’ve been going to fossil fuel company shareholder meetings for the last five or six years. The annual meeting is the company’s turf. It’s their show. Anything that creates this much drama is exactly what they don’t want.

I was stunned that it got to this level. It’s way out of the norm in terms of how these buttoned-up investors operate. Going after the board [as Engine No. 1 did] is a serious ratcheting up. It’s a real sign that investors are impatient, fed up. It’s a strong indication that there’s going to have to be substantive shifts in the company’s direction.

I don’t expect a magical transformation. Exxon has a corporate culture, a swagger around digging and burning. It’s going to take continued pressure from investors, animated by the youth-led climate movement and the amount of activism in this space. There needs to be continued visibility around what happens: Do these new directors get sidelined, or does the company actually put them into important positions, like on the audit committee or the nominating committee?

But this sent a message that reverberates more broadly, and certainly the other major oil and gas companies are taking note. I think that what Engine No. 1 has done could be a model. One could certainly envision Engine No. 1 taking up issues that are climate- or energy-focused with additional companies, or other investors using this as a model on issues of racial justice, human rights, a whole range of concerns where there’s already groundwork to build upon. A similarly positioned investor would now have a lot of leverage to bring corporate leadership to the table, to avoid this kind of situation. For companies that are digging in their heels on issues related to social justice, racial justice, and democracy, I could see something modeled on this tactic sending a powerful message from the investor community.

I think we can expect investors to up the ante next year if ExxonMobil doesn’t respond in some significant way. I don’t know what that looks like, but I wouldn’t want to be [CEO] Darren Woods if they don’t signal a real shift in direction.

Joseph Majkut, director of policy at the Niskanen Center

“The business model that has allowed Big Oil to be a high performer is likely going to have to change.”

As a sign that business as usual is over, as a cultural marker for other investors, I think it’s very significant. It’s ExxonMobil! That’s the big one. It sat atop the oil and gas industry in the United States for decades. The fact that activist investors can come in and effect change in this way is really significant.

As a sign that business as usual is over, as a cultural marker for other investors, I think it’s very significant. It’s ExxonMobil! That’s the big one. It sat atop the oil and gas industry in the United States for decades. The fact that activist investors can come in and effect change in this way is really significant.

The board of directors is really important to the company, and this kind of move is not a vote of confidence in recent decisions. It probably should’ve happened years ago, but here we are. The business model that has allowed Big Oil to be a high performer is likely going to have to change. I think that’s what Engine No 1 was really getting at.

Part of what we’ll be watching as Exxon takes on these new board members is how much they are working within the company: Is the company changing its investment and business practices to reflect that we’ll be living in a carbon-constrained world?

Success breeds success, so I imagine we’ll see other events like this. That said, this doesn’t solve the climate problem.

Geoffrey Supran, research associate at Harvard University; 2020 Grist 50 honoree

“As laudable as this is, if shareholders hope to have a meaningful impact on climate change, they’re going to need to go further.”

I’m excited but skeptical. It truly is a momentous day — a day that offers humanity a glimmer of light. It’s a very clear, decisive message to ExxonMobil and the fossil fuel industry writ large. Shareholders have had enough of business as usual on climate change. It’s seismic in terms of building further activism by shareholders, but the reason it feels seismic is because shareholder activism has yielded nothing for the past 25 years.

I’m excited but skeptical. It truly is a momentous day — a day that offers humanity a glimmer of light. It’s a very clear, decisive message to ExxonMobil and the fossil fuel industry writ large. Shareholders have had enough of business as usual on climate change. It’s seismic in terms of building further activism by shareholders, but the reason it feels seismic is because shareholder activism has yielded nothing for the past 25 years.

That said, we need to be careful in keeping this in perspective. Three rebel board members in and of themselves are unlikely to instantly change things. It’s a cultural and political shift, in the sense that clearly shareholders are ready to change things up a bit. But are they willing to do it at the scale and speed to hold back dangerous warming?

As laudable as this is, if shareholders hope to have a meaningful impact on climate change, they’re going to need to go further, including some combination of the full disclosure of lobbying, or divesting, or firing CEOs. Shareholders and the broader community will need to push for clarity and commitment in terms of the specifics of their pledges and plans.

I think we’ll see pushback from these companies on all fronts — social, political, and legal. This is an industry with 100 years of expertise in the invention and innovation of public affairs, and they will bring all that to bear. But this is the tip of the iceberg when it comes to fossil fuel companies being held accountable by shareholders, lawyers, and the public. It foreshadows what’s to come. I definitely think this would be the first round of aggressive shareholder activism.

David Turnbull, strategic communications director at Oil Change International

“Oil companies are not the strong investments that they once were. The market is starting to understand that.”

Three board members aren’t going to shift that behemoth overnight, even if it were three Naomi Kleins and Bill McKibbens. But it is a big deal because of its unprecedented nature. It might provide some encouragement to other big shareholders out there, that they can be more aggressive on this issue.

Three board members aren’t going to shift that behemoth overnight, even if it were three Naomi Kleins and Bill McKibbens. But it is a big deal because of its unprecedented nature. It might provide some encouragement to other big shareholders out there, that they can be more aggressive on this issue.

The entire industry has got to be on notice that their investments, financial security, and future are really being questioned. I think there’s also some nervousness from investors that they’re going to have some stranded assets on their hands if they don’t align their business with a climate-safe future. The other piece is the volatility of the oil market through the COVID era, which has helped to highlight the fact that this industry is not a sure thing.

I think that recognition is clear across the fossil fuel industry: You need to take climate change seriously or you’re going to be left behind. Oil companies are not the strong investments that they once were. The market is starting to understand that.

The number one thing we’ll look for is whether they’re setting an absolute target of ramping down their extraction. I can’t say I necessarily expect Exxon to announce that in the next year, but that’s what we’d be looking for.

You could imagine different scenarios — one would be the simple recognition that they need to exit the oil and gas extraction business. That would be a visionary approach: In the long term, it would probably provide the highest value for shareholders, because they are planning [for it] now rather than continuing to invest in assets that will have to be abandoned if we’re going to have a livable planet.