Cars aren’t what they used to be. Sure, they have more horsepower, more features, and require less fuel — but they are losing their power over humanity.

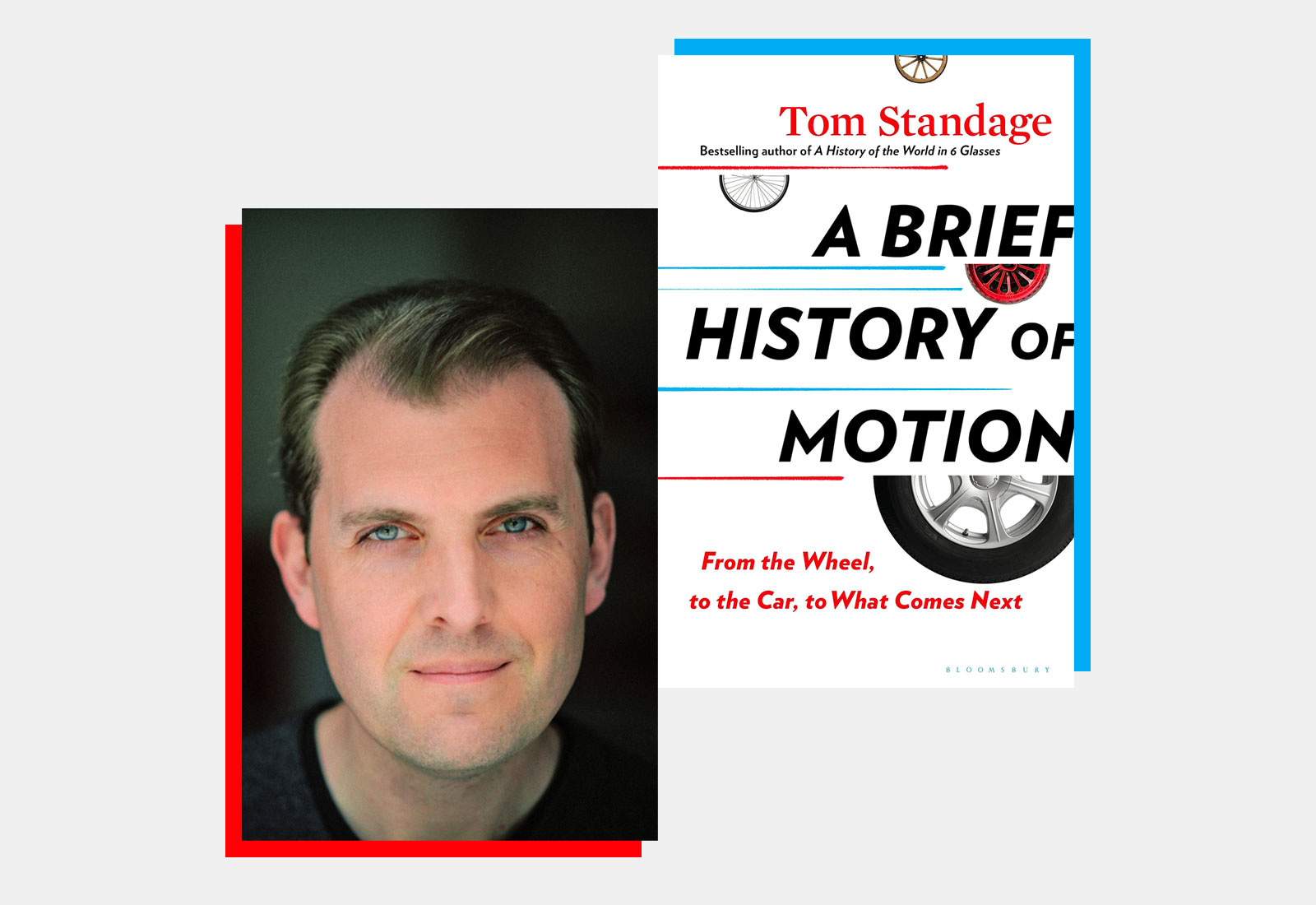

At least that’s the argument in a new book on the history of transportation by journalist Tom Standage, deputy editor of The Economist. In A Brief History of Motion: From the Wheel, to the Car, to What Comes Next, Standage argues the world may have already passed what he calls “peak car” — the point at which car ownership and use level off and start to decline. It can be seen in a drop in the number of automobiles that factories produce each year, the number of miles the average person drives, and the importance of cars in our lives.

Such a trend may seem improbable here in the United States where, starting in the 1950s, politicians bet the entire pot on cars, spending trillions of dollars on multi-lane highway networks and designing cities expressly for automobiles. For decades, cars have become so useful, easy, and expected that people have been willing to accept a terrible price for them: The cost of car ownership, including fuel, repairs, parking, and insurance for the average American is around $10,000 a year, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Then there are the emissions — transportation is the single biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the country and a major source of other pollution. Also, the direct deaths: Every 100 million miles traveled — the distance Americans drive every 4 hours — exacts a sacrifice of one human life, according to the latest statistics from the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Standage’s new book makes the case that things are changing, that automobiles no longer have such sway. In 2017, world vehicle production reached what may be its high watermark — 97 million new vehicles — before falling 1 percent in 2018 and another 5 percent in 2019. Volkmar Denner, chief executive of Robert Bosch, the world’s largest maker of car parts, speculated that companies may never again reach that 2017 level. “And that was before the coronavirus pandemic whacked car sales,” Standage told Grist.

In a new interview, Standage talks about the evidence that the world has passed “peak car,” and about how transportation will change without an addiction to automobiles.

I remember reading in media coverage, maybe 10 years ago, that along with all the other things they’d put to death, millennials were killing cars — but the total number of miles Americans travel in vehicles has increased since then. How can we both be driving farther and leaving cars behind?

The overall number of miles travelled in road vehicles is still rising in America, but more slowly than the number of vehicles or total population. So each vehicle and each person is doing fewer miles per year on average. In fact, the number of miles driven per vehicle, and per person of driving age, both peaked in 2004 and have since fallen to levels last seen in the 1990s.

There is something of a generational effect here. Since the 1980s, the proportion of Americans with a license has fallen from 46 percent to 25 percent among 16-year-olds, 80 percent to 60 percent among 18-year-olds, and 92 percent to 77 percent among those aged 20 to 24, according to researchers at the University of Michigan.

The U.S. is the home of the highway — so perhaps it’s harder for us to imagine such a shift away from car culture. But are there other places farther along the path to peak car?

Yes, other countries are further along, and America will lag them, because it’s the world’s most car-dependent society, spends less on public transit, and so on. In Australia, Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, and Spain, distance driven per person has been flat or falling since the early 2000s.

People used to love cars. So what has changed?

Most people now live in cities, and the decline in driving is chiefly a decline in urban driving. The cost and hassle of car ownership has increased as traffic congestion has increased. For many urbanites, but particularly the young, cars are no longer regarded as essential. The steady shift toward e-commerce means cars are needed for fewer shopping trips. And when a car is needed, for a weekend away or to help a friend move house, car-sharing and rental services are readily accessible.

Also, restrictions on car use in cities have become more severe in recent years. This has even been the case in car-loving America, as shown by the closures to private cars of Market Street in San Francisco and 14th Street in Manhattan, to make more room for public transport.

Ultimately, I think it comes down to this: Cars used to grant people freedom. And they still do. But the costs of that freedom are going up, which is making car ownership less attractive overall.

The world population is still increasing, and there are billions of people rising out of poverty who could afford a car someday. Won’t that increase the number of cars out there?

The obvious test case is China. And car sales, having boomed, have slowed down there. A survey in 2016 by the consulting firm McKinsey found that 60 percent of Chinese consumers no longer considered owning a car to be a status symbol, and 40 percent said that owning a car seemed less important. The growing Chinese middle class, which has shown itself to be receptive to new services and products, seems happy to skip the hassle of car ownership in favor of on-demand mobility services arranged via smartphone. If that’s the case, then the motor that had been driving global car sales has now been switched off.

Most people reading this probably know someone who moved out of a city during the COVID-19 pandemic. Do you think this exodus could lead to an uptick in driving?

The pandemic caused a drop in driving, and then an uptick as people came out of lockdowns and decided, in some cases, that they would rather drive than use public transit. But the longer-term trend seems clear: driving is becoming less popular, because it’s becoming less convenient, and the alternatives are becoming more convenient. The growing prevalence of remote working may encourage people to move to urban fringes where it’s difficult to live without a car, but overall I don’t think this will be enough to reverse the longer-term trend.

Are we talking about a rapid technological replacement, like cell phones replacing landlines?

This is more like the way that new forms of media, such as audio, movies, and video games now exist alongside books and other text-based media, but have not made them go away. This is good, because in the horse-drawn era we essentially had a horse-drawn transport monoculture, which caused problems, and then we moved to a car-based transport monoculture in many parts of the world, notably in American suburbs. The future of mobility will, I hope, be much more diverse, with all kinds of weird and wonderful forms of transport, from e-scooters to passenger drones, being knitted together by smartphones, what I call “the internet of motion.” And as we move into that sort of environment, and start to unpick the automobile from the fabric of everyday life, we’ll realize just how much the modern world has been shaped by our over-dependence on cars.

This interview has been edited for length.