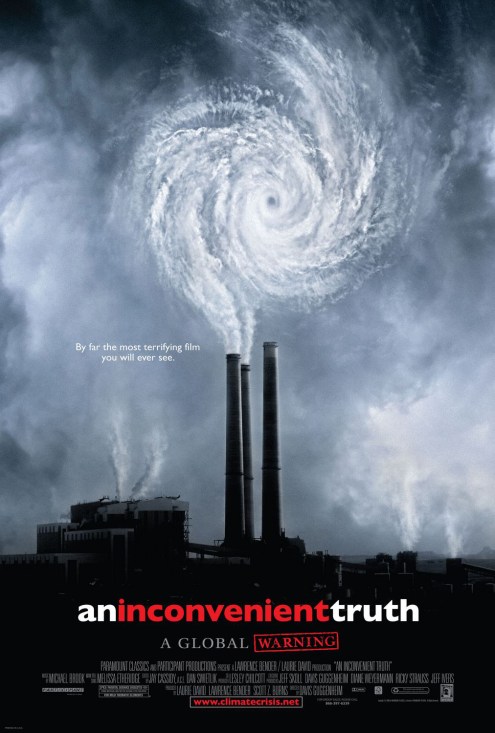

A decade ago, climate change was a huge problem with a small audience. Unless you were among a handful of brave policymakers, concerned scientists, or loyal Grist readers, it’s fair to say the threat of a rapidly warming world took a back seat to High School Musical, MySpace, and whether or not Pluto was a planet (yes, those were all a thing in 2006).

Then, An Inconvenient Truth happened.

Somehow, a film starring a failed presidential candidate and his traveling slideshow triggered a seismic shift in public understanding of climate change. It won Oscars and helped earn Al Gore a share of the Nobel Peace Prize. It injected the issue into policy debates and dinner-table conversations alike.

Did any of this actually “save the world?” OK, you got us. Ten years after the movie’s release, climate change is still a growing threat and a polarizing issue, with record-breaking heat unable to stop skeptics from tossing snowballs on the Senate floor. But we’re also seeing corporate, political, and societal mobilization against the crisis on a scale that would have been hard to imagine 10 years ago, and there’s no question the film played a big part in getting us there.

So how did the movie-makers turn a science-heavy slideshow and unlikely leading man (sorry, Al) into a global force for change? What follows is a behind-the-scenes look at An Inconvenient Truth. As for whether there’s a happy ending, we’re afraid that’s still a bit TBD.

Interviews by Jennifer Keishin Armstrong,

Amelia Urry, Eve Andrews, and Melissa Cronin

With Melissa Etheridge, Lonnie Thompson, and others

Reuters

Al Gore: In April of 1989, I went through a personal epiphany. One of my children had a serious accident. During the darkest days, I re-examined everything that I was doing in my life, how I was spending my time, and what issues I was working on in the U.S. Senate. I had been holding hearings about the climate crisis, but during that spring of 1989, I very much deepened my emotional commitment. I started putting together a slideshow and doing research for my book, Earth in the Balance. I had previously made presentations on the subject, and I had used some visual aids with fold-up charts. But I began collecting pictures. I worked with National Geographic and some others and put together a slideshow that involved three Kodak carousels and three Kodak projectors. The slides would fade in and fade out, and the three projectors did their thing in sequence. I thought it was pretty cool.

Long before anybody talked to me about a movie, I got to the point where I could tell the slideshow was beginning to get some real traction. Probably the most important moment for me was one Saturday night on Center Hill Lake in Middle Tennessee, near where I live. A whole big gang of my rowdy friends were on the front of the houseboat drinking beer. One thing led to another, and I started giving the slideshow about midnight. I mean they’re friends, but I would say they were a tough crowd in that they were not the audience you would necessarily pick for a presentation on the climate crisis. But they had reactions that were strong, positive, very sincere, and they were moved by it. I thought to myself then, I really need to figure out a way to get this in front of more people.

[pullquote class=”pullquote–ait” share=”true” hashtag=”#ait10″ tweet=’“I did not see how in the world a slideshow could become a movie.” An oral history of ‘An Inconvenient Truth’’]”I thought that was a bad idea, if not a crazy idea. I did not see how in the world a slideshow could become a movie.”[/pullquote]

Laurie David, producer: I was working on this issue myself, largely with the Natural Resources Defense Council. When the movie The Day After Tomorrow came out, I was asked to moderate a panel the night before the premiere in New York City. I think the scientist Michael Oppenheimer was on the panel, Al Gore was on the panel, and a few other people. As the Hollywood person, I was the moderator. It was a really great marketing idea for this film. They had a packed house. I knew Al Gore from the elections and meeting him at people’s houses out here in Los Angeles. But I didn’t know him very well. I introduced him at the panel, and he did, like, an eight-minute version of his presentation, which I had never seen before. My jaw dropped. I had been killing myself trying to find the language to explain this issue to people in a way that they could digest. Here Al Gore had it. I was just floored.

Al Gore: She came up to me afterward and said, “This has to be made into a movie.” And I thought that was a bad idea, if not a crazy idea. I did not see how in the world a slideshow could become a movie.

Davis Guggenheim, director: I was working at Participant Media at the time. I was the guy in charge of documentaries, and I had only been there for four months. By all accounts, including my own, I was the worst executive at Participant. I’d given my notice. It was my last week or two. And Lawrence [Bender] and Laurie came in and they said, “We’re doing this documentary about climate change with Al Gore.” I was like, “I’m not sure that’s a good idea.” A movie about climate change was very timely, but one based around a slideshow? I thought, maybe these are the wrong elements for a good film. And I think a lot of people felt that way throughout. A movie about a slideshow? With Al Gore and all the baggage that came with the 2000 election? This makes no sense.

Laurie David: At the time, everybody was mad at Al. Blamed him for giving up on the election too soon. It was not easy to get people to come hear him speak. I had to literally call people personally and beg them to come to a presentation in New York. They were like, “A slideshow with Al Gore, are you kidding me?” I worked my ass off. I put my reputation and friendships on the line, and they came. He got a standing ovation. People were floored. Then I did the same thing in Los Angeles. I got the rooms donated and invited all my Hollywood friends and producers and actors and actresses.

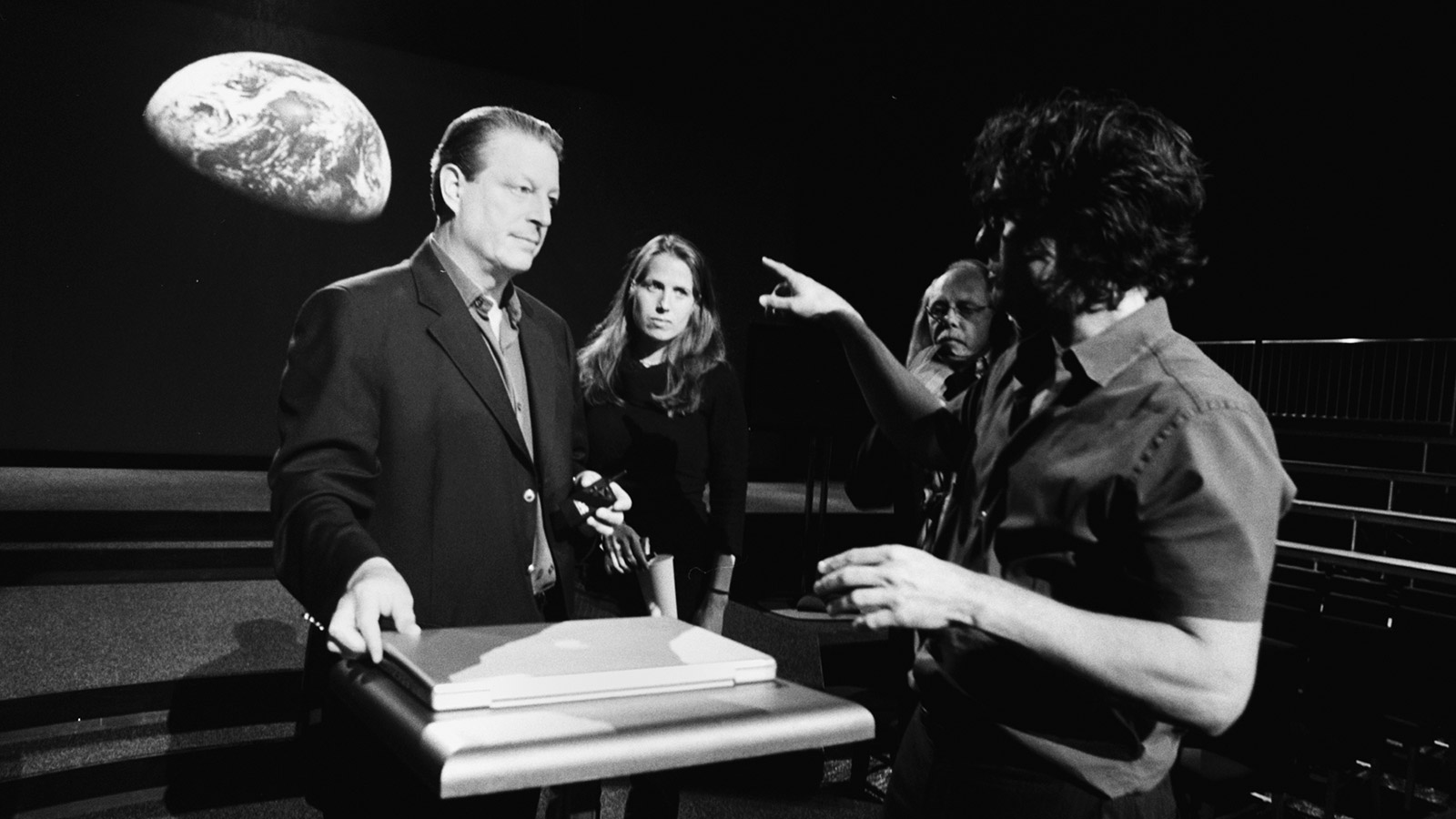

Davis Guggenheim: One of Laurie’s gifts is that she is very unrelenting. She said, “You have to come to this presentation. Al Gore is going to give the presentation at the Beverly Hilton in a couple of weeks.” So I went to the presentation against my will. And Al got up, and I was like, OK, here he goes. I don’t see this.

And then there is a certain point in the middle of his slideshow where everything sorta clicks. It was towards the end, when the slideshow becomes very existential and very challenging, and you start to think about life on this planet. I think all of us just looked at each other and said, “We have to make this movie.”

Lawrence Bender, producer: Imagine, we wanna make a movie about a slideshow from an ex-politician, and we want a million dollars. Who’s gonna give us that? Who in their right mind would do that?

Davis Guggenheim: We set up another slideshow at CAA, the talent agency. I remember in the middle of it, there was an earthquake.

Jeff Skoll, executive producer: I was front and center, right next to Tipper, when the building started to shake.

Davis Guggenheim: All of us were like, “Oh my gosh, is this going to screw up the slideshow? Everyone’s gonna go running.” But the people who hadn’t seen the slideshow, including Jeff, I don’t think even felt the earthquake because it was so engrossing.

Jeff Skoll: Afterward, my team at Participant came up to this small conference room at CAA. There were other people in the room, I don’t remember exactly who they were, but it was definitely Laurie and Lawrence and me, and Davis, and Al. And we had a conversation.

Two important things happened in that room: I decided to fund the whole film on the spot, and Davis agreed to leave Participant and go direct the film immediately.

Al Gore: They just convinced me that they had the skill to do things I couldn’t imagine doing. I decided: Well, they seem to know what they’re talking about, and maybe this could reach more people. Little did I know.

Reuters

Davis Guggenheim: This movie was made in five and a half months. Most of my movies take a year and a half, if not two and a half. We all felt like we were on a mission from God just to make it as fast as we could. We just felt like it was urgent. The clock was ticking, and people had to see it.

Lesley Chilcott, co-producer: All the logic of, take your time making the film, do it the correct way, travel to a million film festivals, get feedback, revise — that was all out the window.

Davis Guggenheim: When people look back, they start to write a narrative in their head about why it was so successful. And in many ways, it makes no sense. It’s a huge tribute to Al and the slideshow, which he had built for 30 years. It wasn’t something he had just come up with. He had perfected it and perfected it and perfected it.

Al Gore: I’m driven by a real passionate sense of mission on this. I hope that doesn’t sound like a pretentious word. I really feel driven to communicate this as effectively as I can. I think I’m obsessed with trying to make each slide the best, most persuasive image it can be, while also keeping the full integrity of the data it represents. You just develop a sense over time of what connects with people and how you can connect even better. I guess there’s a touch of OCD somewhere. But I did become obsessed, and still am, with trying to really craft each slide to be as eye-catching and communicative as it can possibly be. And it turns out, after you get into the innards of the process, you get to the point where — this will sound ridiculous — but it makes a difference whether a transition is two-tenths of a second or three-tenths of a second. And I’ll go to 0.15 or 0.175. That is silly, but I do it anyway.

I showed Steve Jobs early versions of the slideshow several years before the movie came out. He recommended Keynote. Let me insert my own recommendation to anyone who’s putting together slideshows: It is by far and away the best such program. Of course, I’m on the board of Apple, so I’m biased. But early on Steve actually asked one of the Keynote specialists at Apple to help me learn all of the ins and outs of the program. So this guy volunteered his time, but I was so ravenous for more and more help that eventually Steve had to say, “Al, I think we’re going to have to get you a contractor.” It got to the point of: OK, we’re not going to create a new division of Apple for Al Gore’s slideshow.

Davis Guggenheim: I would guess at that point he was giving it 50 to 100 times a year. I remember being on a plane to China with him, and he was changing the slides on his laptop from English to Mandarin. Every show, he would be changing it. But you can’t just film a slideshow. When you’re in the room with Al, you’re sort of blown away, because there’s the man in front of you. But it’s like a rock concert: You’re there and you’re blown away, but when you watch it on TV, it’s just not the same. It doesn’t sound the same, and you don’t have that personal intense feeling, like you’re in the moment. So I immediately felt that we needed to add a personal narrative and had many long discussions about how to do this.

Al Gore: I didn’t like that, either. I really did not. I just felt like: What is it about my personal story that has any relevance to this?

Davis Guggenheim: There are stories in there about his sister dying of cancer, of his son being injured in a car accident, of him losing the 2000 election. Those are all very raw moments, and you could say, “What do those have to do with climate change? How does this fit?” I honestly didn’t have the answer to that.

Lesley Chilcott: Because he was this public figure that had always been heavily edited, people didn’t know his real voice. It took us several months of following Al, I think, before we earned his trust to tell the election story, of what had happened. Initially, he didn’t want to talk about it. Why would he?

Davis Guggenheim: I remember going to get a drink with Scott Burns, who was one of the producers. He’s great, and he’s very smart. And he was saying, why don’t you look at the movie The Last Waltz, this film by Martin Scorsese about the last concert by The Band? It intercuts between The Band performing these songs and then backstage in other places to these little vignettes. It has a wonderful structure to it.

I remember going home and looking at it and saying, “Oh, this could be.” You can just leave completely from a live moment to a non-live moment. And that’s true in An Inconvenient Truth. You go from him presenting this thing to him as a college student. You go back to the live show, and then there’s him as a senator. The Last Waltz was a breakthrough for me.

Scott Z. Burns, producer: We had to tell the story of Al, because he was someone who we hadn’t heard much from since 2000. He was a guy that seemed to have vanished behind a beard, and people didn’t know what he’d been up to. And when we saw that it was something so important and so transformative — I think it made me completely reconsider him. He was no longer a victim of a really unfortunate moment in American history, but a guy who had gotten up off the canvas after a pretty severe blow and turned his attention to something so important, with so much intellect and passion and insight. I felt like it was a great comeback story that we could tell at the same time that we were telling the story of climate change.

Davis Guggenheim: There’s this big moment in the film, this big “aha!” moment, where he shows the CO2 levels rise. So we got to the point where we made this 90-foot-wide screen. The idea was, with that big screen, how great would it be for him to walk the length of that screen. But then you’re kind of stuck, because if you do the math, you’ve got to get him 40 feet up in the air. So we had talked about a ladder, we had talked about a hoist.

Finally, we were like, well, let’s order a scissor lift. And I remember getting the scissor lift and teaching him how to go up. In the first presentation, the audience was there and it was going really well. He did it perfectly, he went up, and the reveal was great. Then it’s time to come down. And he doesn’t know how to come down.

Scott Z. Burns: Al is smart enough to recognize that when you’re talking about something that serious, unless you allow for laughter, you lose the audience inside themselves. Laughter really allows a connection for community.

Al’s line in the movie, “I used to be the next president of the United States,” was such a bold move on his part, because it diffused that whole issue. It made you reconsider the entire guy before he said a word about climate change.

Lonnie Thompson, scientific adviser: I think his depth of understanding is much greater than what you see in the movie. He really tries to seek out the best information possible.

He would have these science breakfasts. I remember being really impressed at one stage when I was talking about these ice cores and the fact that we measure isotopes. Al Gore stopped me and said, “Lonnie, let me tell them what an isotope is.” I was always impressed with how rapidly he could pick up information.

Melissa Etheridge, musician: This was 2005, and I had just recovered from breast cancer. My life was really changed, and I was just looking for new pathways, new meaning in my music. And I got a phone call from Al Gore. Like, “Hello, Melissa, it’s Al Gore.” He started talking about what he’d been doing, this global warming slideshow. He was gonna do it in L.A., and did I want to come see it? I said, “Sure, absolutely.” And I’m thinking it’s a little slideshow, and he said, “Well, they’re filming it, and I was wondering if you wanted to write a song for it.”

Of course, there was absolutely no budget to record it, so I basically called my band in and said, “Hey, we’ve got a couple of hours, can you knock this out?”

Davis Guggenheim: The first location shoot that we scheduled was New Orleans. Al was excited to go there because he was speaking at an insurance industry convention, because insurance adjusters were ahead of most businesses in acknowledging that climate change was happening. They were seeing the effects of hurricanes on insurance claims. We had bought our tickets, we had our crew. And I remember the shoot was on a Friday, and come Tuesday before that, there was talk of this hurricane coming. What do we do? We all felt like we should still go, but we got calls that said, “Don’t come. It’s too severe.” I don’t know if they canceled the convention or not, but we couldn’t shoot. And the flights wouldn’t leave, so we canceled our shoot. And that hurricane became Hurricane Katrina.

It became one of the key moments of the movie. It’s in our opening, where you see Mayor Ray Nagin talk about the horror that’s happening. You see the sea-level rise, you see the levees break. But it also became one of the key moments where just everyone else in the world felt, oh, this climate change thing is real. The interesting thing about climate change is it’s this threat that everyone understands, but it’s so existential. You can’t touch it. You can understand it, but then it’s not in your life every day. With Hurricane Katrina, suddenly it felt real to everybody.

Courtesy of Participant Media

Al Gore: I thought that was a bad idea, too. We had of course batted around a number of possible titles. It’s sort of like picking a URL. Once you start, it’s a cul-de-sac that you can’t escape from. So we’d bat them around for a while and call it quits and go back and do something productive.

Lesley Chilcott: Davis and Al and I had many, many debates about it.

Davis Guggenheim: We had a lot of really bad titles. One was The Rising. I remember Al talking about whether he should give Bruce Springsteen a call, because he had an album out called The Rising. It had a great triple-entendre, because it was like the sea-level rising and the idea of people rising. So we got excited about that for a while.

Lesley Chilcott: On an intellectual level, it makes sense: The Rising! The temperature is rising, everything is rising — everything in the movie, all the graphs, go from the lower left to the upper right. And we’re like, “Technically it makes sense, but it does sound like a horror movie.”

Davis Guggenheim: There were also some really bad ones like Too Hot to Handle. Maybe that’s not right, but it was something with “hot,” ya know? We had a lot of hot puns.

Then I was interviewing Al at his home. I think we had at least 12 interviews, and he would tell you that they were excruciating for him. I kept pushing him and pushing him and pushing him in the way that I do.

Al Gore: Boy, did he ever. I was not fully prepared for what a skillful interviewer Davis was. You don’t hear his voice in the movie at all, but he did a series of taped interviews just with audio tape, not with the camera on, and plumbed the depths of what was going on in my mind and heart when I dealt with this issue. I’m telling you, at times, he would kind of remind you of an exchange you would have with a child, where you give what you think is a pretty good answer, and then the next question is, “Yes, but why?” Then you peel back a layer, and you come up with something that’s a little deeper and more introspective. And then the response is, “Yeah, but why?” He kept on going, and pretty soon I was saying stuff that I understood myself for the first time.

Davis Guggenheim: I generally don’t like people’s first answers to things. And especially someone as polished as him, someone who is crafting his message so carefully. Sometimes a well-crafted answer is not good for a film. It wants to be raw and in the moment, and you want to feel like it’s found as you’re making it, like he thinks of it at the time he’s saying it. So I ask, “Why is this so hard for people? I get the logic of the argument for climate change, but why is it so hard for people to grasp?” And he goes, “Because it’s an inconvenient truth, ya know?” I had never heard him say that. I don’t know if he had before. And he said it in a string of a long answer, but in the back of my head, I go, that’s the title of our movie.

I gotta tell you, it was not a popular title in our discussions. For a while, I was defending it vigorously against other titles, and people thought it was hard to say, people thought it wasn’t fun, it wasn’t sexy. Days before we went to Sundance and had to decide, there was a large group of people who did not like the title.

Al Gore: My immediate reaction was, “Nah, I don’t think so.” And again, I was flat wrong. That’s become a common phrase in popular culture, and you see it over and over in different contexts.

Melissa Etheridge: He was happy that I worked “an inconvenient truth” into the song. I didn’t know how I would do it — it’s not the most singable lyric — but I was able to do it.

Reuters

Davis Guggenheim: Right before Sundance we took the film to a major studio. This studio had everyone there, it had the head of the studio, the head of production, the head of development — every executive who worked at the studio — because Al came. To his credit, he flew in for the meeting ’cause it was too important. We showed it for them, and several of the executives fell asleep in the screening. I remember listening to one of them snore, then waking up awkwardly when the lights came up.

I remember the executives going into another room and huddling, then coming back and the head of the studio saying to us, “We do not believe that anyone will pay to have a babysitter come so that they can go see this movie. Stop dreaming — this movie will never have a theatrical release. But we believe in what you’re doing, we like you, and as a favor to you, we will make, for free, 10,000 DVDs that you can send to science teachers.”

[pullquote class=”pullquote–ait” share=”true” hashtag=”#ait10″ tweet=”“I did not doubt that this was going to change the world.” An oral history of ‘An Inconvenient Truth’”]“I did not have one doubt that this was going to change the world.”[/pullquote]

Lawrence Bender: There were naysayers along the way — a lot of naysayers along the way.

Michael Feldman, Gore political adviser: I immediately went to the dark side, thinking about how it could be mocked, or whether people would think it was a political move.

Jeff Skoll: At one point, Al was doing his presentation to a group of mayors at Sundance — these were all mayors who had come to talk about climate change. But he had to do another presentation that night in Minneapolis. So I flew all of us and our crew and Davis and Lesley and Al to Sundance on a small private plane. We got there and we did the presentations and then we went to Minnesota.

The plane itself was parked in a farmer’s field and it had filled up with all these mosquitoes from the lights of the plane. Imagine you put eight people in a plane filled with mosquitoes and you shut the door and take off — it was bedlam. We were all slapping mosquitoes, making a mess of the plane. I didn’t really know Al that well at that point, but I saw a mosquito on his upper leg and without thinking, I just slapped it. Al gave me a look of shock. I said, “Oh, I’m sorry, sir.”

Davis Guggenheim: Everything changed when we took it to Sundance. We had an afternoon slot, which is not a great slot. We were not in one of the great theaters. Then we screened the movie with an audience, and I’ll never forget when the lights came up. I think someone said there were three standing ovations. I don’t remember, but the response was unlike any movie I’ve ever been a part of. The applause didn’t stop, and the people just rushed towards Al. We pushed out this side door and went to a friend’s house where there was a small reception. I think it was maybe 50 of us. We all kind of can’t believe it. Then suddenly these calls start coming in, these offers to buy the film. And there were a lot of them.

Jeff Skoll: Participant went to Sundance with two documentaries that year: One that we thought would go straight to PBS, and one that we thought would actually be appealing to a global audience. Well, the one documentary you know; the second one was a film called The World According to Sesame Street. We figured this is the one that would have popular appeal, and Al’s film maybe would go straight to PBS.

In the end Paramount signed up to distribute the film. Our other film, The World According to Sesame Street, went straight to PBS.

Laurie David: I did not have one doubt that this was going to change the world in some way. We had so much passion and were so convinced of it. But then you say, “How do you get the audience to come?” Don’t forget, there was no social media then. There was no Twitter, none of that. I remember going to all the environmental groups to get their base out the first weekend. Once people started seeing it, we knew word of mouth was going to be great. One of the huge successes of the film was that every morning show, every newspaper, every magazine wrote about it. And by writing about the movie, they’re writing about the issue. That was huge.

Megan Colligan, Paramount marketing executive: We did promotional screenings. We were asking people either to pledge to see it again or to bring a friend or to encourage a friend to go. It was almost like a voter registration drive. You’re voting with your $8, and that $8 is going to be the thing that is going to spark awareness.

Diane Weyermann, executive producer: It ended up doing a massive $50 million box office around the world. It’s incredibly unusual for a documentary film to reach that number of people, and climate change wasn’t really a subject that people were talking about.

Lawrence Bender: Thousands of documentaries are made, only a handful get in the movie theater, only a handful break a million dollars at the box office, a small handful every year.

Lesley Chilcott: We came out at exactly the right time. There are so many amazing groups that had been talking about this issue for so many years, and there was finally something that they could all point to.

Jeff Skoll: In 2006, before the film was released, there was a poll that showed about a third of Americans felt that climate change was an important issue. And in 2007, the year after the film was released, that 33 percent went up to something like 85 percent. There was a huge jump in awareness.

Diane Weyermann: I remember going to the Academy Awards that year. Al Gore on the red carpet was like pandemonium, which we didn’t necessarily expect — everybody wanting his attention, taking his picture, yelling out to him. It was really wild to see Al Gore the rock star.

Michael Feldman: People wanted a piece of him again, in a way that was unlike when he was in office. I think in some ways, it almost took being out of office, in political no-man’s-land, to use these other levers to have an even bigger impact on this issue that he really cared about.

Al Gore: Davis got the Academy Award, but I have visiting rights. Before they announced the award, they had asked me and Leo DiCaprio to go out on stage and make a comment about how the Oscars was greening itself. At the time, there was some speculation about me maybe running for president again in ’08. My daughter Kristin, who is a screenwriter in Hollywood, wrote this part of the script where Leo said, “Al, isn’t there something else you’d like to announce?” And I looked at him, and I said, “Well, I really wasn’t planning to, but …” Then I pulled out a prepared statement.

You know how the orchestra will start playing music when your time’s up? During the rehearsal, I told the conductor, “You come in full blast, you gotta cut me off right away.” That’s how they did it, and it was really fun.

NASA

Al Gore: I don’t want to sound like a nutcase, but I am driven to do this. I’ve got several slideshows in the next several days. I gave several last week. I still work on it every day. I worked on it this morning. There’s so much new science that comes out almost every day now. It doesn’t really change the overall scientific story, but thankfully the solution side has changed significantly. With all of our discussion of the movie, I don’t want to lose sight of the fact that we’re still facing a threat to the future of civilization. We’re making great progress, and we’re now getting close to the point where we can imagine turning the corner and starting to get the upper hand, but we’re not there yet. I could not imagine for a moment slowing down. I ask myself every day, what else can I do to be more effective?

Courtesy of Lonnie Thompson

Laurie David: For a long time, you couldn’t see the impact of global warming. Now you see it every friggin’ day. That’s what was so powerful about that slide where you see the water rising, what it would do to cities. That was using imagination at that point. But you can see it now. You can see what’s happened with the Arctic. You can see what’s happened with glaciers. You can see the sea level rising. And of course the storms and the drought. Every other day there’s a huge, once-in-a-lifetime weather event. I think one of the most amazing things about the film is how much of it was right-on. He was right about everything.

Scott Z. Burns: I was at the climate march a year and a half ago in New York City, and I was blown away that there were millions of people in the streets. I do feel that the film helped tie some shoes and get some people out there.

Al Gore: It sounds like false bravado to say I’m just getting warmed up, and I don’t want to put it that way because I’m getting older. But I feel like I’m just getting warmed up in the sense that I continue every day to try to figure out ways to communicate effectively. I think it’s beginning to have a real impact. I spoke at the United Nations on Earth Day when 175 countries came to sign the Paris agreement. The U.N.’s never seen anything like that before. I’m very excited now that we’ve got a real chance to win this. The only remaining concern is it matters a lot how quickly we win it.

Melissa Etheridge: It’s never all you want it to be, but that’s not the way change happens. Change happens slowly. We’re totally moving in that direction, and we’re not ever going back.

Laurie David: There were millions of dollars spent by corporations to confuse the public about this issue. Millions and millions and millions spent by the coal and oil industries. Where would we be if private-interest money wasn’t spent deceiving the public? How much further along would we be? I think initially we thought there would be more attacks against the film directly. But there wasn’t anything in the film that wasn’t true. They weren’t able to attack the film directly. So the money went into misinformation campaigns in the public: The science isn’t complete, not everybody agrees, there are two sides to this. This is how they confused the public. It was a targeted, organized campaign to spread misinformation on global warming.

It’s a problem that’s only going to be solved if the whole world unites. And I think the whole world did unite in Paris, finally. The drought, the wildfires … everything he talked about is happening, but it’s happening faster. That’s the only thing we maybe were a little off on, how fast everything has happened. We’re not talking about our grandkids’ future now. We’re talking about our future.

Davis Guggenheim: When we ended up doing press for the movie after it came out, we would quote Jim Hansen, the great NASA scientist, who basically modeled the most important predictions of what climate change would do. He said we have 10 years to make significant change or we will do irreversible damage to the Earth. And we are now 10 years from when we made the movie.

I’m hopeful because Al’s new slideshow, which he continues to do, is more hopeful. There’s a lot of reasons to believe. A lot of the progress is exponentially better than we had imagined. Yet I am terrified for my children. The existential acceptance of this issue is still dormant. Even amongst the people who accept that climate change is real, those people are not doing enough. There are moments where I’m up at night worrying, but the rest of the time I sort of glide through my life, pretending it’s not there. I drive an electric car, I have solar panels on my house, I vote the right way. And yet even my response is not up to where it should be.

So I feel like we can blame all the bad guys, but the truth is, all of us who believe it’s real still aren’t doing enough. Maybe the only person in the world who is, is Al Gore.