Amanda and Drew Heyen spent 16 years in their small ranch home on Chantilly Lane in Houston’s Central Northwest neighborhood. In that period, their house flooded nine times — more than once every two years. At first, they tried to live with the frequent inundations. They raised their furniture on cinder blocks and installed an industrial kitchen sink with no cabinetry.

After the eighth flood, in early August 2017, they decided to make plans to move.

A storm had passed, leaving a couple inches of water in their home. Amanda was hauling debris to the front lawn the next day when she turned to her husband. “I don’t want to live here anymore,” she said.

But they couldn’t get out before flood nine, Hurricane Harvey, arrived two weeks later. The Heyens bounced between motel rooms and friends’ houses for weeks. They returned home more than a month later to find that mold was growing on parts of the walls and that sections of the roof had caved in. “The computer room didn’t have a ceiling,” Drew said.

The Heyens eventually repaired the house and moved back in, but the two were determined to unload the house as soon as possible. When Drew talked to prospective buyers, he recalls fielding some offers in the $50,000 range — nearly half of the roughly $90,000 he and his wife had spent on the house sixteen years earlier.

When Amanda and Drew Heyen returned to their Houston home after Hurricane Harvey, they found extensive flooding (right) and part of their ceiling caved in. Courtesy Amanda and Drew Heyen

The Heyens found themselves with a difficult choice: They could take a major loss on the home. Or they could file flood-insurance paperwork, repair the house for the ninth time and hope for a higher appraisal later, knowing full well that their home was likely to take on more water than more value.

Floods cause more deaths and property damage in the United States than any other type of natural disaster. As climate change accelerates, they are getting worse and a growing number of Americans are signing up to have local governments “buy out” their disaster-prone houses, often with money from grants awarded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Among cities with populations over 500,000, Houston leads the pack on buyouts made possible with FEMA funds. Harris County, home to the Houston metro area, has bought nearly 2,400 homes as of this past June. Next on the list were Nashville, Charlotte, and Louisville — but Houston has bought thousands more houses than each of the runners up. FEMA calls these transactions a “win-win” because they rescue distressed homeowners and allow oft-waterlogged residences to be knocked down and converted into wetlands, prairies, and other rain-absorbing infrastructure.

But buyouts come with problems. Local officials are primarily reliant on FEMA disaster payouts that arrive after events like big storms. However, to get federal funding, buyout programs need to be 100-percent voluntary, meaning homeowners must want out. But not everyone is so eager to sell as the Heyens, which means counties often acquire a patchwork of homes, as opposed to blocks at a time. Critics, including real-estate agents, accuse local officials of doling out cash haphazardly. And a study released earlier this this year by The Nature Conservancy and Texas A&M University zeroed in on Houston’s buyouts, pointing out risks inherent in Harris County’s uncoordinated pattern of home acquisitions.

The Heyens’ story captures many of the problems with Houston’s current system. The family first considered signing up for the voluntary home buyout program administered by Harris County Flood Control District after their house flooded for the fourth time in 2007. But for years, the money just wasn’t there; there were too many other Houstonians with homes in deep floodplains who faced more dangerous risks from inundations.

But it doesn’t take a flood of Biblical proportions to make people want out of their houses. Home like the Heyens’ exist in a soggy in-between — too flood-prone to accrue value but not dangerous enough to merit immediate rescue. But as a growing body of research shows, keeping these homes around doesn’t just subject families to a frequent aquatic nuisance, it can increase flood risks for the entire city.

It wasn’t until Houston voters overwhelmingly passed a roughly $2.5 billion bond for flood improvements after Harvey that the Heyens finally got an offer on their house from the Flood Control District. But by that point, it was too late. The family had already joined the roughly 5,500 homeowners who sold their Harvey-flooded houses to private real-estate companies, according to an investigation published last year by the Houston Chronicle. Harris County Flood Control District has bought out two out of 25 homes on the Heyen’s old block, whereas real-estate speculators — including some based as far away as Nevada and California — now own at least four.

If the Heyens had their druthers, they say they would have taken a buyout. Doing so would have meant the house would have been torn down — and no one would ever have to suffer through another flood in their house. Instead, they sold their house to Houstonian Investment Group, a company run by Jason Morris, who lives next door to their now former home.

Morris bought the Heyens’ house for around $85,000. After repairing plumbing and electrical issues and making cosmetic renovations, according to notices posted outside the home, he later had it appraised $256,000. As a resident of Chantilly Lane, he knows about the street’s flooding issues. But the investment, he told Grist, was just too good to pass up.

“It was a really good deal,” he said.

In 2001, Amanda and Drew were newlyweds looking to start a family. They thought they had found just the place to raise theirs on Chantilly Lane.

At just over 1,300 square feet, the single-story house was small by Houston standards. But it was cheap and in a good area — filled with verdant parks and decent schools and relatively close to the trendy Heights neighborhood, known for its historic homes and hip eateries. Behind the house, the property line spilled back onto a bayou called Brickhouse Gully. The backyard was enormous, Drew said, “easily as big as the house.”

According to county flood maps, the home was built in the 100-year floodplain — meaning the Heyens’ new place had a one percent chance of taking on water each year. Problem was, the house, built in 1965, had flooded at least twice in the 1980s and 1990s, as well as the year before, during Tropical Storm Allison.

The Heyens knew this history. But weighing the risks against the price, they took the plunge (literally, they’d eventually learn) and bought the house. “We get flood insurance, we repair the house, we move on with our lives,” Drew said, describing their thinking at the time. “It seemed like a reasonable trade-off.”

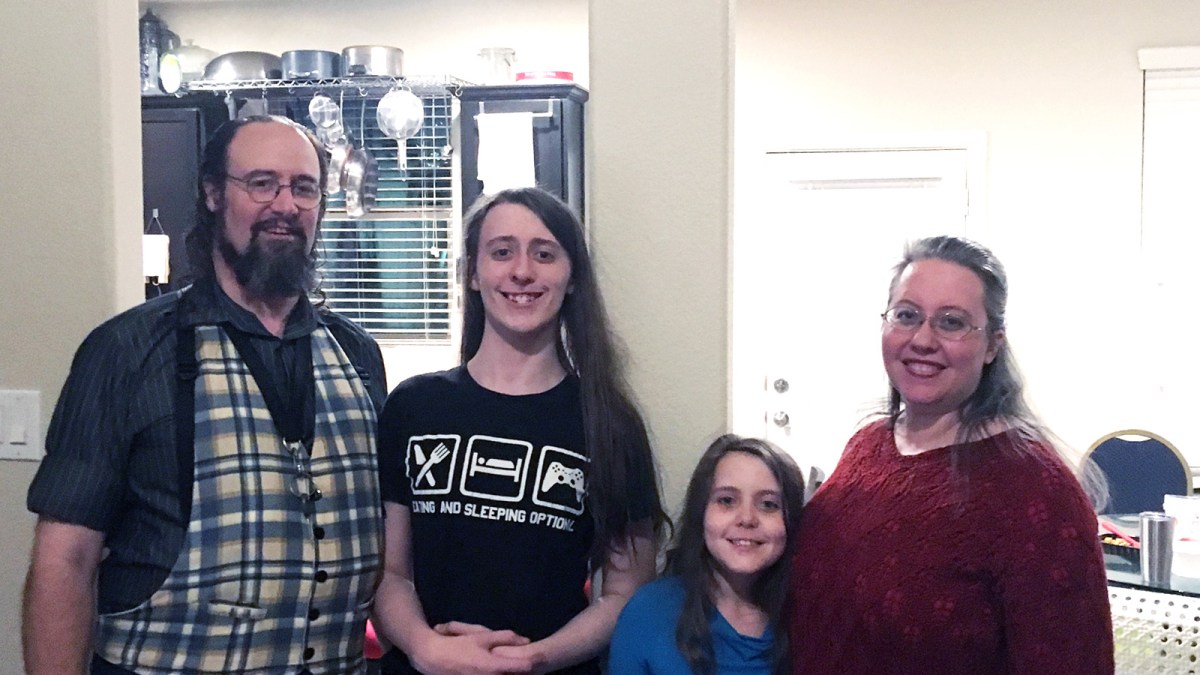

Amanda and Drew Heyen in their new home along with their children, Paul (second from the left) and Helen. Stephen Paulsen

The first flood arrived about a year after they moved in. A rainstorm ushered in four to five inches of water. A second flood, in 2003, was minor enough that it didn’t ruin the Heyen’s carpet. But then the house flooded again in 2004.

The Heyens started rebuilding their house in preparation for future floods. In addition to raising their furniture and installing an industrial sink, they tore out the carpet and parts of the wall. Drew joked that their kids, unlike many other children, actually picked their toys off the floor.

When new county flood maps came out in 2007, the Heyens realized why flooding was a recurrent problem for them. The maps revealed their home was not actually in a floodplain but rather a “floodway,” a natural path for flood waters. As the Heyens saw it, they lived in a river.

The news came as a disappointment to the Heyens, who make right around Houston’s median household income of $64,00. Amanda Heyen is the breadwinner in the family. She works for a local commercial real-estate company. Drew is a self-described “stay-at-home dad” and the King’s Magician at the Texas Renaissance Festival, a yearly gathering of medieval enthusiasts in the forests north of the city. He also home-schools the kids: Paul, now 14, and Helen, 8.

While the frequent flood-inspired home repairs weren’t bankrupting them — they had flood insurance, after all — their house was proving to be a burden.

Around 2008, Harris County Flood Control District was interested in buying houses on Brickhouse Gully. It sent out fliers. Canvassers with the agency knocked on doors and talked to residents about the buyout program. The Heyens qualified, at least in theory. But the agency didn’t have the money to buy their home just yet, and wouldn’t consider Chantilly Lane a priority until around 2015.

Then Harvey hit. Billions in federal disaster relief dollars started slowly flowing to the city, and Harris County got a fresh influx of flood-mitigation funds. After Harvey, around 4,000 Houston residents applied to the buyout program and around 1,000 were accepted, according to Rice University’s Kinder Institute for Urban Research.

A year after the storm hit, as local officials waited on funding, only around a dozen homes in the accepted into the buyout program had completed the process of being turned over to the county. Around 20 percent of the eligible homeowners had accepted offers from other buyers — the Heyens included.

Every year, when the Harris County Flood Control District acquires new flood-prone houses, it turns them back to nature, tearing down the homes and letting animals, plants, and floodwaters do their thing. It’s possible to imagine a day in the not-so-distant future when every Houston residence is safely elevated above the floodplain, with large buffers of greenspace around the city’s many waterways. Parks would flood instead of houses.

If you look at a chart of voluntary home buyouts in Houston, you’ll notice they spike from 2002 to 2004 — just after Tropical Storm Allison, which resulted in 23 deaths and $5 billion in damages. It was Houston’s worst flood until Harvey. There’s another rise in buyouts after Hurricane Ike, which in 2008 made landfall as a Category 2 storm and piled up nearly $30 billion in damages across Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas. The number of buyouts in Harris County started climbing soon after Harvey, as well. There were 63 in 2017, 102 in 2018, and roughly 200 thus far in 2019. James Wade, who runs the Voluntary Home Buyout program in Harris County, said he expects the number to climb again over the rest of this year and into 2020, as Harvey victims continue to volunteer to leave their homes.

In the days after Hurricane Harvey, more than 1,000 residents called the Harris Flood Control District in to request buyouts of their flood-damaged homes. David J. Phillip / AP

As a method for expanding and reinforcing Houston’s rain-absorbing infrastructure, the Flood Control District’s buyout program has had some real successes. In north Houston, it’s converted (by its estimates) 200 of the 223 homes in the Arbor Oaks community into a park and wetland, which soaks up floods and protects surrounding neighborhoods. Instead of fighting the natural flow of flood waters, the county adapted to it.

The voluntary nature of home buyouts helps explain why their numbers spike after disasters — and also why officials can’t always buy up a whole subdivision, like Arbor Oaks, at once. In the recent study from the Nature Conservancy and Texas A&M University, researchers said Harris County should make buyouts in a more coordinated way. “The more open space you can preserve, the better the benefit you’re going to get,” Lily Verdone, director of freshwater and marine at The Nature Conservancy in Texas and a lead researcher on the study, said. “You can get more bang for your buck by having clustered properties.”

Uncoordinated buyouts result in what experts call “checkerboarding,” because the mishmash of empty lots and standing homes resembles the red-and-black squares of the game board. Checkerboarding makes it harder to ensure the land will “serve the greatest benefit” to residents in the form of a park or flood-abatement project, according to Elyse Zavar, a geographer at the University of North Texas who has studied these issues.

Although a lack of funds and reluctant homeowners hamstring buyout operations, experts say real-estate speculation makes the problem even worse, inserting a profit motive into the already expensive and heart-wrenching process of buying up flood-prone communities. And when companies rent the properties or sell them to a homebuyer, it passes the buck, endangering a new crop of residents rather than reducing risk by taking homes out of rotation, flood officials say. In a statement to Grist, FEMA expressed concern about speculators buying “‘distressed’ properties in flood prone areas.” “The end consumer may not be fully aware of the flood risk to properties that they purchase or rent,” the agency warned.

Wade said real-estate speculation in buyout areas is “a public-safety issue” for residents and first-responders, as well as “a drain” on the public dollars used for infrastructure and the National Flood Insurance Program. He admits that the Flood Control District hasn’t always coordinated its buyouts, but he notes that since Houston approved around $2.5 billion expenditure for flood improvements, there’s been more local money on hand. And that’s allowed Wade’s agency to be more proactive. “If there are properties for sale on the open market in those buyout areas, we’ve taken the position to use local money for those properties rather than wait for them to qualify for grant funding,” he explained.

But those early buyouts have created pockets where flooding is a regular occurrence and the Flood Control District will have to spend much more money to acquire large tracts of homes, said Ed Wolff, president of Beth Wolff Realtors in Houston. In the increasingly chic Meyerland neighborhood in southwest Houston, the median house price has climbed to around $400,000 from less than $300,000 in 2009. It’s a recipe for checkerboarding.

“We have brand-new construction above the floodplain,” Wolff said, adding that it sits next to “vacant land that can never be bought without an act of Congress.”

So today, residents of the flood-prone area — including Wolff himself — have been elevating their homes up to six feet or so off the ground knowing that the Meyerland’s rising home prices likely mean the county will spend its buyout funds elsewhere. In lieu of acquiring more properties, there is some work going on in the area that could result in the mitigation of future floods. One block away from Ed Wolff’s home, Flood Control and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are expanding Brays Bayou with the goal of pulling the surrounding area out of the floodplain and making it safe for residents.

Market forces are yet another obstacle standing in the way of a fully coordinated buyout program. Officials can’t just take properties from people or companies— buyouts, after all, are not a form of eminent domain. And records from Harris County show that home buyout money often goes to private companies with real-estate holdings, as well. It’s one way Jason Morris could make good on his investment in the Heyens’ home.

If the Heyens’ flooding problem was so bad, why did they stick it out so long on Chantilly Lane?

A listing on the real-estate website Zillow, posted by the Heyen family before they sold to Jason Morris, says it all. Sure, they warn that the house carries “a repetitive flood risk,” but they also note that it’s in a “great area with great neighbors.”

The Heyens’ former home on Chantilly Lane in 2019. Notices on the door describe work being done to the plumbing and electrical systems. Stephen Paulsen

From his vantage point next door, Morris agreed. He figured one day, someone would buy the house from Houstonian — or else, the company would sell it to the county. With his new appraisal well over $200,000, the county would probably offer him that amount to buy it and tear it down. When Flood Control finally did offer to buy the Heyens’ house, shortly after they agreed to sell to Houstonian, it offered $90,000 — $5,000 more than Morris bought it for. Even if he never sold the house and just waited for a buyout, he could still turn a profit.

Morris bristled at criticisms that by acquiring the house instead of Flood Control he was in some way contributing to continued flooding. From his perspective, the county had plenty of time to buy the house. But they didn’t — and he stepped in.

For now, the Heyen’s former home still sits vacant. On a recent visit, the house was dark. The shades were drawn, and a heavy metal gate covered the front door. A sprinkler watered the front lawn. The front windows were covered with notices, approving repairs to the plumbing, as well as other flood-related issues. Not on the window: A permit to raise the house on piers, as many chronically flooded Houston homeowners, like the residents of Meyerland, are doing. Morris has no plans to raise the home, he said; but if someone buys it, he insists he’ll tell them about the flood risks.

If the flooding returns, he said flat-out that county officials should step in. “If we flood again, they should not let us re-do our houses,” he said, knowing that would apply to his own house, too. No more repairs and renovations: just tear the damn things down.

As for the Heyens, they’re now high and dry in a suburban neighborhood about six miles away from Chantilly Lane. But they can’t shake the feeling that, in their haste to extricate themselves from the only house their family had called home, they’ve doomed another prospective family to a life of frequent flooding.

They remember having one last chance to spare anyone their fate in late-2017. The Flood Control District finally offered the Heyens a buyout, just as they were closing their contract with Morris’ company, Houstonian Investment Group. The Heyens tried to accept the agency’s offer, but Houstonian sued to keep control of the flood-prone house and protect Morris’ investment.

The family decided against a costly legal battle, even though Drew believes they would have won in the end. He sometimes wonders if they should have fought for the buyout. “The idea that no one else would move into that house was very important to me,” he said. “Nothing in the world could make me happier.”

Except maybe avoiding that tenth flood.