This story was co-published with Fast Company.

David Peters’s nightmare began on a Monday in the spring of 2016, just before the end of the work day. Peters was the assistant public works director for the city of Stuart, a community of 18,000 on southeast Florida’s tranquil Treasure Coast. One of his many duties was to help oversee the municipal drinking water supply, a responsibility he took seriously. That afternoon, Peters was told that an administrative aide for the U.S. representative from Stuart’s district had left a message with the city asking someone to call her back.

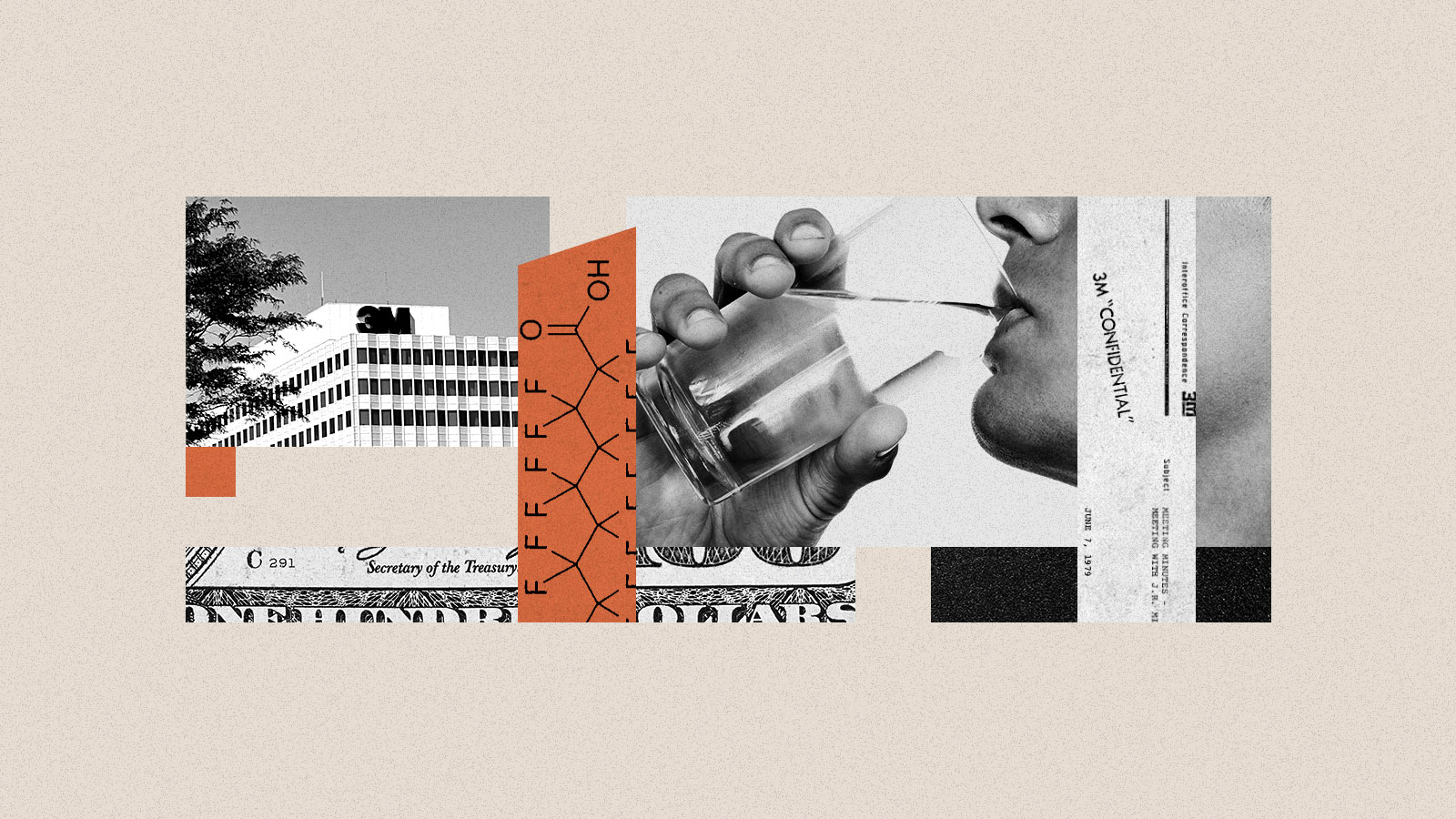

“Are you prepared for this?” the aide asked when Peters returned her call. The rest came very quickly. The state had identified a class of chemicals linked to cancer called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as PFAS or “forever chemicals,” in Stuart’s drinking water supply. The chemicals were at dangerously high levels.

Peters, who had never even heard of PFAS before, emailed Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection for more information. The department explained that in 2012, the federal Environmental Protection Agency had added, for the first time, two types of PFAS — pronounced PEA’-fass — to its list of “unregulated contaminants” that public water systems must test for. Stuart had run tests in 2014 and 2015 and found both chemicals, PFOS and PFOA, in its water supply. But the city and the state environmental agency hadn’t thought much of it, since the contamination, at a combined 200 parts per trillion, or ppt, was not thought to be at a level that was harmful to human health.

But in May 2016, days before the legislative aide called Peters, the U.S. EPA issued a new policy: Levels of the two PFAS in drinking water, the agency said in a national health advisory, should not exceed 70 ppt.

What this meant was that Stuart’s public water utility — winner of multiple awards, including a statewide “best-tasting water” competition — had been unintentionally poisoning its constituents. Subsequent testing showed some of the city’s individual wells had levels of PFAS higher than 1,000 ppt. There was no way to turn back the clock. People had been drinking the poisoned water, and no one knew for how long.

Thus began, Peters told lawyers in a 2021 deposition, a “week in hell.”

Peters collected himself and began to devise a plan. By the end of the week, the city had discovered that levels of PFAS in water from all of the city’s municipal wells averaged out to 65 ppt, just 5 ppt below the EPA’s new standard, and had pulled its three most contaminated wells offline. Peters and other officials weren’t satisfied. They had been caught off guard once, and they weren’t willing to let it happen again.

“We weren’t about to take a chance on getting caught with a system that wouldn’t treat down to below detection levels under any circumstance,” Peters said in the deposition. The city’s goal since 2016 has been to get PFAS contamination in its drinking water supply to “non-detect,” or as close to zero ppt as possible.

But achieving non-detect status has proved to be wildly expensive and, ultimately, out of reach for a city of Stuart’s size and means. Conventional water-purification techniques, such as the use of chlorine, don’t work on tiny and persistent forever chemicals. So the city implemented a new water scrubbing system in order to rid its 30 wells of PFAS. The system, which is called an ion-exchange treatment, relies on magnetlike resins to attract PFAS molecules. The resins, once loaded up with contaminants, have to be incinerated to destroy the chemicals. The city has spent roughly $20 million keeping its PFAS levels below 30 ppt — a maximum limit Stuart set for itself — thus far. It estimates that the cost of replacing the resin, which cannot be reused, is approximately $2 million per year. That cost will increase incrementally as the city strives to get its contamination level down to zero.

“We can’t afford to spend that kind of money every year,” Peters said in his deposition. “We’re a small utility, a small municipality.”

Stuart’s efforts to clean up its water are at the heart of a lawsuit of epic proportions that could have wide-ranging financial repercussions for more than 100 million Americans in the years to come. The trial, which was set to begin in early June, has been delayed as the defendants mull a settlement. If the case goes to trial as planned, Stuart’s lawyers plan to argue in federal court that the companies that manufactured and distributed PFAS not only contaminated Stuart’s water supply, but did so knowingly for decades. They will make the case that those companies, not the city or its residents, should cover the cost of cleanup for Stuart — and for any other city with similarly contaminated drinking water.

The question underpinning the case is one that has consumed Peters’s professional life since 2016: Once you know there’s poison in the well, who’s responsible for getting rid of it?

PFAS do not naturally break down in the environment over time. Their resistance to decay is what makes them useful. It’s also what makes them dangerous.

In 1938, a scientist at DuPont De Nemours and Company, commonly known as DuPont, discovered the first PFAS chemical that would be widely used by Americans in the home — Teflon, the patented name for the type of forever chemical that makes certain cookware nonstick. But the multinational chemical conglomerate 3M quickly became the nation’s chief producer of PFAS. The company manufactured the chemicals for use in its own products and sold them to other chemical companies, like DuPont, for their products, too. PFOA, PFOS, and the thousands of other obscurely named acronymic chemicals under the PFAS umbrella were added to millions of products Americans used — and still use — on a regular basis: pizza boxes, seltzer cans, contact lenses, dental floss, mascara, rugs, sofas.

3M started winding down PFAS production in the 2000s under pressure from the EPA. The company recently announced that it will cease production of forever chemicals entirely by 2025. But the hundreds of millions of pounds of the chemicals the company produced for more than half a century still persist, indefinitely, in the environment. They’re also lingering inside of us: in our blood and our excrement, primarily via the foods we eat and the water we drink.

A growing body of research on the health ramifications of years of sustained exposure to PFAS paints a frightening picture: The chemicals have a disturbing affinity for blood. Once they find their way to the bloodstream, they stick to blood cells as they course through every organ in the body. Studies show PFAS can weaken immune systems and contribute to long-term illnesses like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer — specifically, testicular, kidney, and prostate cancers. A recent study linked PFAS in drinking water and household products such as food packaging to startling decreases in fertility in women. Studies on prenatal and childhood exposure to PFAS show adverse developmental effects, including low birth weight and accelerated puberty.

Since Stuart’s water crisis in 2016, the body of research illuminating the harmful health effects of PFAS has become more robust, prompting the EPA to take more forceful steps to limit consumer exposure to these chemicals. Earlier this year, the EPA proposed a set of new guidelines for six PFAS, including PFOA and PFOS. Unlike its 2016 health advisory standards, these limits — 4 parts per trillion, down from 70 ppt — are enforceable, meaning that water-supply managers must adhere to them or face fines. It’s the first time the agency has taken such a step, a move that underscores just how poisonous the EPA believes PFAS to be, even in minuscule amounts. The decision to regulate PFAS represents a huge win for public health. That win will come at a cost.

The new standard, once it becomes official later this year, will trigger a nationwide effort to rid drinking water supplies of forever chemicals. The projected costs of eliminating PFAS from the water supply are astronomical, beyond the scope of what cities, utilities, and the average consumer can afford. Preliminary estimates suggest that the price tag on filtering forever chemicals out of America’s drinking water is more than $3.8 billion per year. That cost will get passed on to consumers, unless the companies responsible for creating the contamination in the first place are forced to pay. That’s where Stuart’s lawsuit against 3M comes in.

The product at the center of the lawsuit, which will be heard in the U.S. District Court for the District of South Carolina, is called aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF, which has been used by the U.S. military and local fire departments, including Stuart’s, across the nation. The foam’s key ingredient — what makes it so effective at putting out fires — is PFAS. Stuart is arguing that 3M and other manufacturers of ingredients used in firefighting foam knowingly pulled off one of the largest mass poisonings in American history and, crucially, that they hid what they knew about PFAS from the government and the general public in order to continue selling their products.

3M and the other defendants in the case maintain that their products can’t be tied to the plaintiff’s PFAS contamination and therefore they are not liable for the cost of cleaning it up. 3M “will vigorously defend its record of environmental stewardship,” the company said in a statement to Grist. “3M will continue to remediate PFAS and address litigation by defending ourselves in court or through negotiated resolutions, all as appropriate.”

3M has settled multiple PFAS-related lawsuits since 2005, including multimillion dollar settlements with Minnesota and Michigan. But the company has never admitted liability for the contamination the lawsuits alleged.

Stuart’s lawsuit is what lawyers call a “bellwether case” — it’s the first of more than 4,000 lawsuits that have been filed by cities, utilities, and individuals against 3M and other manufacturers of AFFF. Lawyers on both sides carefully chose Stuart as the most representative plaintiff out of the thousands of cases after analyzing the city’s water samples, reading through thousands of documents in the legal process known as discovery, and even exploring the city in person. Stuart’s case will serve as a litmus test for the lawsuits in line behind it, determining how lawyers for the other plaintiffs move forward with their respective arguments. If Stuart succeeds, 3M could be on the hook for one of the biggest mass tort payouts in U.S. history. If it fails, everyday Americans could see their water bills balloon in the years to come.

“3M is a corporate giant that was built in no small part on the profits of these PFAS chemicals. They contaminated drinking water supplies and people across the United States,” David Andrews, a senior scientist at the Environmental Working Group, an environmental health nonprofit, told Grist. “Holding them accountable is significant, both in terms of direct cost to consumers but … also as a signal to companies that produce industrial chemicals about the long-term costs of some of these chemistry decisions.”

Grist spoke with the plaintiffs’ lawyers and reviewed hundreds of documents filed in court to build a narrative account of the years leading up to Stuart’s discovery in 2016, including details about what 3M knew in the 1970s about the dangers its products posed to the general public. Some of the information in this article, including testimony in which a former 3M toxicologist admits that global PFAS contamination can be linked to 3M, has never been reported before.

“We’re dealing with something that is unprecedented in scope and scale,” Rob Bilott, the environmental attorney whose work investigating the chemical industry’s role in manufacturing forever chemicals was instrumental in bringing public attention to PFAS in the early 2000s, told Grist. Bilott, who initially sued DuPont for poisoning communities in West Virginia, is also involved in this new round of litigation.

“It’s going to be incredibly expensive to deal with this,” Bilott said. “I think it’s important for the public to know how much this company knew about the hazards of these materials.”

The USS Forrestal, the Navy’s first “supercarrier” ship, was gearing up for an attack off the coast of Vietnam on the morning of July 29, 1967, when a rocket accidentally slipped loose from a fighter plane idling on the ship’s huge deck. The rocket fired across the runway and pierced another jet. Hundreds of gallons of fuel flowed from the damaged plane, spreading quickly across a deck that had been stocked with aircraft, artillery, and bombs in preparation for the attack. When the fuel encountered a lingering rocket spark, it started a fire that raged for 24 hours, killing 134 people and injuring 161.

The conflagration was one of the deadliest naval disasters on record since World War II.

The Navy convened two separate panels to investigate what happened aboard the Forrestal. The resulting reports, aimed at improving “warship survivability,” recommended ships carry larger quantities of more effective firefighting foams.

In the 1960s, when the company was best known to the public for its masking tape and abrasive sponges, 3M began working on a new type of firefighting foam in collaboration with the Navy. They called the foam “light water,” but it’s now better known by its technical name, aqueous film-forming foam. The foam worked better than conventional firefighting foams and had a virtually unlimited shelf life.

In short order, light water became the firefighting foam of choice by the American military at home and abroad. By the 1970s, it had become a staple — not just on Navy ships, but also at military bases, commercial airports, and, ultimately, local fire departments across the country.

AFFF’s active ingredient, what makes the foam so good at smothering blazes, is “fluorinated surfactant,” otherwise known as perfluorooctane sulfonic acid, or PFOS. For decades, the foam, which was sprayed on real fires and just as often used by fire departments to conduct firefighting drills, was routinely dumped over the sides of ships and onto bare earth, where it leached into the environment and migrated into local drinking water supplies. 3M started winding down production of AFFF in 2000 as the EPA ramped up pressure on the chemical giant to disclose information about its products. But other companies stepped in to fill the void.

Stuart’s fire department began purchasing drums of AFFF from 3M in 1989, according to its lawyers — a decision that would later haunt the city. Court documents show the fire department often used AFFF to conduct training exercises in the field behind the firehouse. Once the city started analyzing water samples from the city’s 30 interconnected drinking water wells, it didn’t take long to discover that the samples with the highest levels of PFAS were located near the fire house.

On May 31, 2016, days after Peters’s call with the administrative aide, all personnel in Stuart’s fire department received a terse email from the city’s fire chief. AFFF was not to be used anymore except for in emergencies, it said, “effective immediately.” The PFAS firehose had finally been shut off, 27 years after it had been inadvertently turned on.

“At no time during the relevant period did the Defendants warn Stuart Fire Rescue that the ingredients in the AFFF were persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic,” Stuart’s legal complaint reads. 3M, as well as Dynax Corporation, Tyco Fire Products LP, Buckeye Fire Equipment Company, Chemguard, and National Foam Inc. — the other defendants in the case — exposed “thousands of innocent residents to water contaminated with dangerous chemicals,” the complaint alleges.

Though the Pentagon recently began to transition to PFAS-free firefighting foam — leading state and local firefighting agencies to do the same — the chemicals are still where fire departments left them for half a century.

What 3M knew about the effect its products had on human health comprises the main thrust of Stuart’s lawsuit against 3M and the other companies that manufactured and sold AFFF. The city’s lawyers have obtained millions of pages of official and unofficial internal company correspondence via discovery. If the plaintiffs can marshall the evidence contained in those pages to convince the jury that the PFAS industry knew its chemicals were widespread among the general public and suspected they were harmful to humans, the jurors may find the companies that produced these products liable for damages. Stuart’s argument, which will be echoed by the 4,000-plus plaintiffs waiting for their day in court, hinges on a few crucial moments in the late 1970s.

Company records, produced in discovery and filed in court, show that executives at 3M started to have an inkling their products were harmful to human health in 1975. That year, two independent scientists called 3M — the main mass-manufacturer of PFAS at the time — to inform the company that they had found PFAS compounds in their own blood and other blood samples. 3M pleaded ignorance. But actions taken by executives in 3M’s upper ranks in the months and years after the company was contacted by the scientists show that the company didn’t remain ignorant for long. 3M found out that PFAS were not only in its employees’ blood, but circulating widely in the blood of the general population, and that the chemicals were potentially carcinogenic. The company kept that information from the federal government, its factory workers, consumers, and the general public.

In 1976, 3M found forever chemicals in the blood of its factory workers, and internal laboratory tests on monkeys and rats had produced worrying results. In June 1978, 3M’s commercial chemical division sent a confidential letter to 3M’s general counsel and executives in the company’s medical and research departments. The company’s president of U.S. operations, Lewis Lehr, had “specifically requested” that 3M meet with an outside consultant to see whether its products containing PFAS were toxic. 3M hadn’t reported its tests to the EPA, which legally requires chemical companies to test and report the health impacts of their products, particularly if they appear to be harmful to humans. Lehr, the letter said, wanted “an independent opinion as to whether we are correct in our assumption that we do not have a reportable situation.”

The first outside expert the company spoke to was a renowned toxicologist named Harold C. Hodge. 3M executives flew to San Francisco to meet with Hodge in April 1979. According to the notes that a 3M staffer drafted at that meeting and are included in the cache of lawsuit documents, Hodge recommended that the company reduce its employees’ exposure to forever chemicals. The draft notes also include an addendum Hodge added by phone about a week later, after he had reviewed more study results provided by 3M. The company, he said, should figure out if PFAS were in the general population and, if so, at what levels. “If the levels are high and widespread,” he said, “we could have a serious problem.”

The next day, 3M executives met with another expert, J.R. Mitchell, from the Baylor School of Medicine in Houston. Draft notes from that meeting show that Mitchell told the company that some of the results from its studies on PFAS in animals “are similar to those observed with carcinogens.”

But the official meeting notes from both meetings, disseminated within the company in June 1979, do not include either of those statements by the outside experts. 3M struck them from its official records. Despite accumulating copious evidence that its products were widespread in the general population and posed serious risks to human health, the company neither alerted the EPA nor ceased production of PFAS. In the years that followed, 3M produced approximately 100 million pounds of POSF, the precursor to the chemical used in AFFF. It and other PFAS chemicals brought in $300 million in annual revenue for 3M.

3M has never publicly admitted that any of the forever chemicals found in samples from around the world could be linked to its products. But ahead of the trial, and over 3M’s vehement objection, the judge ruled that a deposition given by John Butenhoff, a former toxicologist at 3M who worked at the company for nearly four decades starting in the 1970s, could be considered as evidence in the case.

In a video of that deposition, one of Stuart’s lawyers asks Butenhoff a series of questions about where PFAS have been found. “You’re aware that PFOS has been detected and reported in rivers and streams?” the lawyer asks.

“Yes, I have awareness of that,” Butenhoff replies.

The lawyer lists off other places PFAS have been found: soil, sediment, the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, drinking water, human blood, umbilical cord blood, breast milk, shellfish, fish, indoor house dust, outdoor air, and polar bear blood. Butenhoff confirms that the chemicals have been found in all of those places.

“In each and every one of these media all around the world,” the lawyer asks, “the source of PFOS is more likely than not 3M, correct?”

“I think that more likely than not the source is 3M, yes,” Butenhoff replies.

While 3M was raking in billions from its PFAS products, cities like Stuart were unknowingly digging themselves into a pit.

The costs Stuart has had to shoulder, and potential long-term health consequences for the Florida city’s residents, could have been avoided if the defendants were upfront about the dangers of PFAS, Stuart’s lawsuit says. “Had Defendants provided adequate instructions and warnings, the contamination of the groundwater and drinking water supply with toxic and carcinogenic chemicals would have been reduced or eliminated,” it says. “Defendants’ conduct was so reckless or wanting in care that it constituted intentional or grossly negligent conduct.”

Stuart is not alone in its battle against forever chemicals. The prohibitive cost of getting PFAS out of local water supplies is a reality local officials and water providers across the nation are grappling with as the EPA prepares to codify its enforceable standards in the next several months. Once the standards are enacted, utilities will have three years, until 2026, to comply with them.

The federal government has directed roughly $10 billion to help the nation address its PFAS contamination problem. That pot of money includes $2 billion worth of grants to help alleviate the cost of cleaning out contaminants from drinking water in small or disadvantaged communities. But experts say even $10 billion is a drop in the bucket; some estimates put the total cost of ridding the entire nation’s water supply of PFAS somewhere between $200 billion and $400 billion. An estimated 1 in 20 Americans have forever chemicals in their drinking water, a figure that could increase as smaller utilities that were not required to test for PFAS between 2013 and 2015 start looking for them.

There is no easy solution to this problem; every path forward includes expensive equipment and laborious treatment processes. If Stuart and other cities aren’t successful in getting 3M to pay for the damage, the costs will be shouldered by tens of millions of utility customers, also known as ratepayers.

“The ratepayer is paying for the capital, they’re paying back a loan … and they’re paying for the personnel, the equipment, the replacement parts, the electricity,” Steve Via, director of federal relations for the American Water Works Association, an international coalition of water suppliers, told Grist. “All of it comes back to the ratepayer.”

The American Water Works Association analyzed the cost of PFAS cleanup for utilities and households in a report published in March. The typical American household located in an area where PFAS cleanup must take place is looking at an average annual cost of between $200 and $350 per year, which would be passed on to ratepayers through their water bills, according to Via. But there are disparities depending on the size of the community. The annual cost of PFAS for households in large communities is much lower than it is in small ones, where fewer ratepayers share the financial burden. In those less populated areas, the annual cost tops $1,000 a year — a significant expense for the average family.

“This is going to be expensive,” Via said. “None of these systems have been saving money in advance for this because they didn’t know they were going to be required to treat to 4 ppt.”

Sara Hughes, a professor of water policy at the University of Michigan, said some communities will be able to bear these costs more comfortably than others. In poorer communities, especially smaller ones where the average cost of PFAS remediation is much higher than the projected national average, the burden will be felt more acutely.

“For households that are already living on the edge, one more thing, one more bill, one more increase in the cost of living, can be pretty significant.”

“Even $20 more a month means very different things to some households than others,” Hughes said. “For households that are already living on the edge, one more thing, one more bill, one more increase in the cost of living, can be pretty significant.”

The upfront financial cost of remediating the contamination these companies knowingly put into the environment is one facet of the long-term burden American families will face. But the larger and ultimately more devastating consequence is the impact PFAS has had, and will continue to have, on health. These chemicals have already been linked to various cancers, diabetes, infertility, childhood developmental delays, and other issues scientists are still uncovering. Many victims of PFAS poisoning don’t even know that their ailments may be linked to these chemicals, but their lives and bank accounts will feel the impacts.

To this day, 3M’s position on PFAS, according to its website, is that they are “safe and effective for their intended uses.”

Stuart’s lawsuit will probe the strength of this assertion. The more than 4,000 AFFF lawsuits comprise what’s called “multidistrict litigation,” a type of legal proceeding that’s similar to a class-action lawsuit. They fall into multiple categories: The first, spearheaded by Stuart, is made up of water-supply contamination cases. The next bucket of complaints will be personal injury cases — people who claim that exposure to PFAS in firefighting foam led to cancer diagnoses. Many of those plaintiffs are current or former firefighters. Yet more plaintiffs seek restitution for property damage caused by PFAS contamination.

In the months leading up to the scheduled start of the bellwether trial, 300 cases per month on average were added to the multidistrict litigation. As of April, the total number of plaintiffs was 4,173.

The costs of dealing with PFAS contamination are “just now beginning to be recognized,” Bilott, the environmental attorney, said. “I think you’re going to see efforts now underway all over the planet to try to make sure that the people who created this global contamination are responsible for the global implications of cleaning it up.”

This piece has been updated with new information about a potential settlement and a delayed trial start date.