This story was produced in partnership with Osage News.

The sun wasn’t quite high in the Oklahoma sky when Nona and Wayne Roach piled into their old pickup truck, their teenage granddaughter Shaylee perched in the back. It was a hot September morning, but Osage County is known for searing summer temperatures that stretch into the fall. The heat and the hot air swirled around the two-lane road to their horses and cattle.

The Roaches have about 160 acres just outside the tiny town of Avant — population 320 — in the eastern part of Osage County, land that Wayne has worked since the mid-1970s and that his family has owned since the 1930s. He’s a former steer roper who lost two fingers trying to rope a calf on a bet in nearby Nelagoney. His grandfather gave him a calf a year, which is how he got his start.

The terrain is rock-ribbed and full of bluestem prairie, long grasses that are good for grazing livestock. The landscape is graced by bois d’arc trees, sometimes known as Osage orange or horse apple trees.

Then there are the oil wells, both active and abandoned. It’s Osage County, after all, and stories often lead back to oil. For a time in the early 20th century, oil made citizens of the Osage Nation some of the wealthiest people in the world. Martin Scorsese’s recent film Killers of the Flower Moon unravels one thread of that story.

But Nona is more concerned with the present. Why wasn’t she informed when an oil company filed for bankruptcy and just left their equipment on the Roach acreage? Why did it have to sit on her property for so long? Why did no one answer her calls? She’s not alone in her concerns. The Osage Nation is full of “orphan wells,” wells that are done producing and should be capped but often aren’t, left to sicken the land and people around them.

Vast oil reserves were discovered beneath the Osage Nation reservation more than a century ago. Since then, the tribe’s roughly 2,300 square miles in northeastern Oklahoma have become pockmarked with abandoned oil and gas wells.

The companies that drill and operate these wells are legally obligated to close drill holes and clean up sites once they finish extraction, but when they go bankrupt or abdicate their responsibilities, tribal citizens and landowners are left to deal with the fallout.

Left unplugged, these wells become legacy sources of pollution. They can emit methane, a potent greenhouse gas, as well as leak saltwater, oil, and other toxic materials into the surrounding earth, posing an environmental and public health threat. Tribal officials have identified numerous abandoned wells releasing dangerous liquids and gases near schools, playgrounds, and homes.

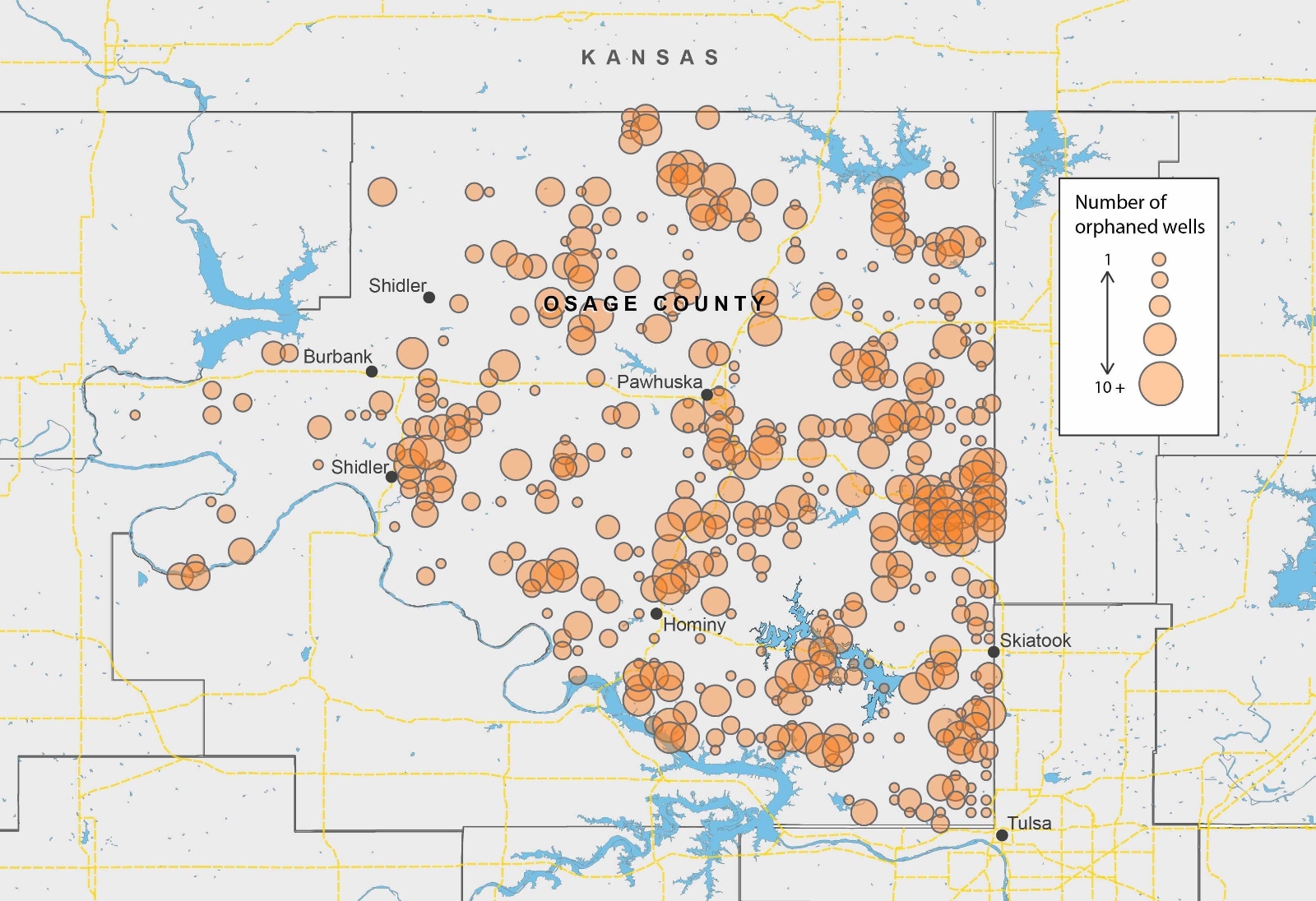

Grist and Osage News analyzed Interior Department data and found that there are roughly 2,300 orphaned wells across the Osage Nation — a higher concentration per square mile than any state, including oil-rich Texas and Pennsylvania. Due to poor record-keeping by federal agencies and officials, the true number could be as high as 16,000. In recent years, the federal government has been stepping in to help clean up the mess, announcing $19 million in funds earlier this year. But with the cost of plugging wells in Osage running anywhere between $40,000 and $500,000 per well, it won’t be nearly enough to fix the problem.

The challenges go beyond funding. Interviews with tribal officials, landowners, and Osage citizens revealed that a slew of bureaucratic hurdles and political challenges threaten to derail the cleanup. What’s more, new rules proposed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA, the federal agency that oversees oil and gas drilling in Osage, continue to do little to hold companies accountable when they walk away from their environmental responsibilities. The regulations fail to address the underlying problem — unscrupulous oil and gas operators — ultimately ensuring the Nation may be dealing with ballooning orphan well counts for decades to come.

To complicate matters, about one-fifth of Osage Nation’s more than 25,000 citizens are shareholders of the tribe’s mineral estate and have a vested interest in seeing oil production increase. The Osage Minerals Council, however, which represents these shareholders, is wary of stricter federal regulations that might scare oil companies away and diminish the tribe’s already waning profits.

There are several reasons for the high concentration of orphan wells on Osage land. For one, oil and gas production in Osage County has been steadily declining since the 1970s. The Exxons and Chevrons of the world left Osage long ago, and a slew of mostly mom-and-pop operators are now squeezing every last drop of oil from wells that are at the end of their lives. Margins are slim, business is tough, and operators frequently go belly-up or leave the county. According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, many of the wells in Osage were orphaned more than a half-century ago, making it impossible to locate the operators responsible for their cleanup. Some were plugged through crude methods long since deemed inadequate.

In Osage County, property owners have a claim to only the surface of their land; the subsurface mineral estate, and the oil within it, belongs to the Osage Nation and is held in trust by the BIA. This arrangement was codified in the 1906 Osage Allotment Act, which relegated all matters pertaining to the Osage Mineral Estate to the federal government.

On average, Osage County produces less than five million barrels of oil annually — a small fraction of Oklahoma’s and the nation’s production. The BIA estimates that almost all of the nearly 300 oil and gas companies operating in Osage today are small businesses, with just two firms responsible for almost 40 percent of production in the county. Approximately 100 producers extract less than 1,000 barrels of oil a year — which roughly equates to less than a barrel a day per well.

“The smaller operators are out there managing and dealing with the wells themselves,” said Trevor Henson, an Oklahoma-based oil and gas attorney who has represented the Osage Producers Association, a trade group. “Those guys can’t survive when the prices go down.”

The BIA has failed for a century in its role of protecting and preserving the mineral estate for tribal members, and the amount that the agency requires operators to set aside for well cleanup is inadequate. Whatever cleanup funds it has collected from operators prior to drilling have also been mismanaged. In recent years, the BIA has had little to no funds to turn over to the Nation for orphan well cleanup. The result of these divergent interests and historical mismanagement is that many Osage citizens, including those without shares in the mineral estate, live on land poisoned with oil.

In response to questions from Grist and Osage News, a BIA spokesperson said that the agency “fully complies” with all federal laws and that the agency is currently revising its oil and gas rules for Osage to “bring them in line with the regulations governing oil and gas leasing and development throughout the rest of Indian Country.”

“The extent of this unmitigated problem is a monumental failure of the BIA to fulfill its trust responsibility for oil and gas development in our mineral estate over the past 100 years,” Paul Revard, a member of the Osage Minerals Council, told a congressional appropriations committee earlier this year. “No other Indian tribe in the United States has an orphaned-well problem like the problem impacting our lands. It is not even close.”

Nona Roach is petite with short, neat blond hair and the no-nonsense demeanor that usually accompanies people adept at navigating federal officials and oil wildcatters doing business on her family’s land. One thing you learn about Nona right away: She can recite the Code of Federal Regulations, or CFRs, in her sleep. The CFRs are the rules that govern oil production and leasing on the Osage Mineral’s estate. According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, these rules require that the agency inform landowners in writing when it approves drilling and plugging permits, and that operators pay commencement fees. But when an operator files for bankruptcy, there are few safeguards in place.

Nearly 20 years ago, Nona noticed a company called McKee stopped operating on her land. Its equipment was idle. No oil was being pumped.

“I kept asking the BIA about it,” Nona said. She called and called. She found out later the company had filed for bankruptcy and that the BIA had terminated its leases. And despite Nona’s many calls, the BIA didn’t tell her. For months, pump jacks and other equipment remained on her land and the wells remained uncapped.

While McKee’s disappearance happened nearly two decades ago, it’s left an indelible mark on the Roaches and their land. In the family truck, Nona cited — from memory — CFR Title 25 Chapter 1 Part 226, which dictates what happens to the equipment when a lease is terminated.

“‘That when lease terminates, all such personal property shall be removed within 90 days or such reasonable extension of time as may be granted by the superintendent,’” she recited. “‘Otherwise, the ownership of all castings shall revert to the lessor and all other personal property.’”

She also points out in that same code the land must be restored “as nearly as practicable to the original state.”

Nona, who has worked for both sides in the oil production business — as an advocate for landowners and to help oil companies navigate regulations in Indian Country — felt like the BIA “did everything they could to make sure we didn’t even know the lease was terminated.”

A BIA spokesperson said that landowners may file complaints regarding operators at any time. “The BIA Osage Agency conducts an inspection and determines what action, if any, is needed,” the spokesperson said.

Wayne Roach says one attempt by a McKee employee to plug a well included cutting down a tree and then sticking its branches into a pipe that juts up from the ground. Then there are the wells, still active on the Roaches’ land, run by the current owner of the lease, a company called Grand Resources. Some of the wells they operate have what is known as a REDA cable that connects the motor to a nearby electrical box. Nona said Grand Resources didn’t use trained electricians and instead used field hands who, in her words, “did a poor job. Those lines have electrocuted and killed cows and horses.”

The Roaches’ property in Osage County has a number of inactive and active wells. Left unplugged, abandoned wells become legacy sources of pollution. Shane Brown / Grist / Osage News

“Our granddaughters could have been fried just as easy as those cows were, because they were here the day before,” Nona said, noting her granddaughters like to ride their horses around the property.

Active wells have leaked saltwater into nearby ponds where their cattle graze, and even more oozed into their bluestem prairie pasture, turning it brown. At one point, Nona recalls, Grand Resources had contaminated two of their ponds with saltwater at least three times each.

In an email, Scott Robinowitz, president of Grand Resources, disputes the Roaches’ allegations, adding that saltwater spills were cleaned up in conjunction with the Environmental Protection Agency and BIA according to their standards. Robinowitz also disputes Nona’s claims about the REDA cable, saying that all work was done by certified electricians.

Robonowitz characterized the relationship with the Roaches as “relatively cooperative but always at odds about something.”

The rules that govern mineral rights on other tribal lands and across the country don’t apply in Osage County, where a patchwork of tribal and federal bodies regulate oil production and the ensuing environmental fallout.

The 1906 Osage Allotment Act is unique to the Osage Nation and was negotiated as part of the Nation’s agreement to allot their surface lands into parcels so long as the tribal nation controlled the subsurface rights. No other tribal nation in the United States has this arrangement.

Since the United States holds the title to the Osage Mineral Estate in trust for the tribe, it gives the federal government sweeping authority over fossil fuel extraction in the county, from issuing companies’ permits for drilling to calculating and distributing profits to shareholders, also referred to as “headright owners.” The BIA carries out these duties as a trustee of the tribe’s energy resources, a legal title that the Secretary of the Interior once described as one of “the highest moral obligations that the United States must meet.”

It plays out like this: Whereas an oil company hoping to drill in West Texas would lease land directly from the owner of a property’s mineral estate, operators in the Osage Nation get permission to drill from the BIA. The Osage Minerals Council, the mineral management agency for the Osage Nation, has the authority to accept bids for leases and works closely with the BIA to represent shareholder interests. According to the BIA, landowners “do not have a say in whether their land is leased for oil and gas mining, who the lessee is, or how long the lessee operates the lease on their land.”

“It’s unique,” said Henson, the oil and gas attorney. “I’m not aware of any individual group that owns all of their mineral estate in America.”

Over the past decade, headright payments have plunged and orphaned wells have endured as a county-wide public health threat. In a 2014 report, the Office of Inspector General, the oversight division within the Department of the Interior, blasted the BIA for policies that led to these conditions. The document, which was published after the Nation reached a settlement with the federal government for mismanaging its energy resources, identified dozens of systemic flaws with the agency’s program, including poorly defined environmental regulations, an antiquated data system, and inadequate protections to ensure oil and gas companies plug wells at the end of their lives.

It wasn’t the first time that the department identified issues with the BIA’s program. In 1990, officials identified many of the same problems, but nearly two decades later, the BIA had failed to carry out most of that report’s recommendations. Correcting these deficiencies, the 2014 report stated, was about more than crafting sounder regulations: It was a matter of fulfilling its trustee duty to the tribe.

“Not only does BIA have the authority, but it also has the obligation to manage the Osage Nation’s oil and gas resources effectively so that headright holders receive the best value for their oil and gas,” the report read.

In an email, the BIA said that it has taken steps to implement the report’s recommendations, and added that the agency fully complies with the National Environmental Policy Act and is working on modernizing existing regulations governing oil and gas leasing on Osage land.

Active wells on the Roaches’ property have leaked saltwater into nearby ponds where their cattle graze. At one point, Nona recalls, the oil operator Grand Resources had contaminated two of their ponds with saltwater at least three times each. Shane Brown / Grist / Osage News

The BIA has rules in place to protect the Nation and landowners from the environmental fallout that might result from a company filing for bankruptcy. But those rules were written in 1974 when the cost of plugging and the number of orphaned wells were lower. Today, those costs are higher in part due to hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, and a limited pool of pluggers.

When an operator applies to drill in Osage, the BIA requires the company to set aside money in the form of bonds in case it’s unable to fulfill its environmental obligations. These financial instruments involve a third-party guarantor. If an operator goes belly-up, the guarantor steps in to provide cleanup funds.

Operators in Osage are required to secure bonds for anywhere between $5,000 to $150,000 depending on the number of acres that they produce on. However, the requirements are wholly inadequate, because a single well can cost anywhere from $40,000 to $500,000 to plug. Collecting $150,000 for dozens of wells means the agency may only have a few thousand dollars — if that — to plug each well.

“Those bonds [were] set back in the 1970s, and it has not been adjusted for inflation,” said Jim Gray, a former principal chief of the Osage Nation. “There’s a justifiable need to update that bond amount just on that reason alone.”

Jim Gray, former chief of the Osage Nation, photographed at Central Park in Skiatook, Oklahoma. “I would think everyone has a shared interest in a successful plugging of a well,” he said, “that no one is in dispute over whether or not it needs to be plugged.” Shane Brown / Grist / Osage News

BIA rules require that companies secure bonds before they can operate in Osage, but historically, the agency has allowed firms to set aside money using a less stringent form of financial assurance called certificates of deposit, or CDs, a type of savings account that generates interest for a defined period of time.

The 2014 Inspector General report found that this type of “promissory note” from the bank doesn’t prevent companies from borrowing the money in the account. That means the operator may have set aside money on paper, but there may not be any tangible funds for cleanup — essentially, an empty promise. The report noted that in addition to allowing certificates of deposit, the agency did not periodically verify the funds to ensure operators weren’t withdrawing from the accounts. In total, the report found the BIA had secured just $5 million in CDs from nearly 400 operators, but because these had been collected as certificates of deposit, the actual money available for plugging was likely lower. The agency stopped accepting CDs in 2014 as a result of the Inspector General’s findings.

By the time the Osage Minerals Council began trying to plug wells in earnest in 2017, most of the money from the bonds and CDs collected had evaporated. In grant application documents submitted to the Department of Interior, the council noted it had been informed by the BIA “that there are no obtainable surety bonds” for the majority of the documented orphaned wells on Osage land. A BIA spokesperson said that there are approximately 300 lessees currently operating in Osage and that the agency has collected bonds from 30 lessees in the last decade. But the spokesperson did not disclose how much the agency holds in bonds or how much it collected from the 30 lessees.

“For more than a century, BIA has had little to no funding to plug abandoned wells on our Mineral Estate and failed to hold oil and gas developers responsible for plugging their wells,” Revard, the Osage Minerals Council member, told a congressional committee in March.

To complicate matters further, no tribal or federal agency seems to know for certain just how many orphaned wells there are in Osage County. In a letter to Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, Everett Waller, the chairman of the Osage Minerals Council, said the BIA had developed a list of approximately 1,600 abandoned wells by 2017. Using money provided by Congress during the past few years, the council has located almost 700 more. Sources in Osage County described the true scope of the problem as uncalculated, and say the current list of documented wells is likely a vast underestimate.

On its website, the Osage Minerals Council hosts a database of more than 40,000 oil and gas wells across Osage County that it says was created by the BIA. In an email, the BIA said they could not vouch for the authenticity of the data as it was maintained by the Osage Nation and not the federal government but would not confirm if they maintained a similar dataset. Approximately 16,000 of the wells in the list are designated as “ABD,” or abandoned.

Revard added that the true number of orphaned wells is unknown, many of the drill holes never registered in tribal or federal data.

“Some wells were drilled without permits,” he said. “So there’s no record of it. It wasn’t an honest thing to do, but it happened.”

Oilfield detritus near an oil well on Nona and Wayne Roach’s land. The true number of abandoned wells in Osage County is unknown, with many of the drill holes never registered in tribal or federal data. Shane Brown / Grist / Osage News

After the BIA failed for years to address Osage County’s orphaned wells, the Minerals Council decided to take matters into its own hands. In 2016, it appealed to Congress for funds to tackle the problem, and was granted $3 million in 2018 and an additional $1.1 million in 2022. The council got to work assembling a well-plugging committee, which involved identifying wells that posed the highest risk to communities and the environment and finding a group of contractors to close them up. The council has plugged more than 80 wells in Osage County using all of those funds.

In his congressional testimonies over the years, Revard has described the monumental challenges associated with plugging some of the trickier abandoned wells. In one case, the council closed a well that was leaking oil onto a school softball field, only to discover that it had begun venting gas from another opening nearby. To plug a different well, contractors had to reroute a creek and move a hill to haul equipment as well as avoid railroad tracks that ran along the site.

Those railroad tracks are “just one example of how our communities have grown up around these wells,” Revard noted. “Oil and gas development in the Osage Mineral Estate occurs in the same place where our families live, work, and play.”

Given its experience with well-plugging over the last several years, the Minerals Council applied for $49 million of additional funding from the Interior Department early this year, but found out a month later that its grant application had been denied. In its rejection letter, the agency explained that “the Osage Minerals Council is not eligible under the definition of a Federally Recognized Tribe as described in the guidance document.” Instead, $19 million of the funds would go to the Osage Nation, which had submitted its own application for $91 million over five years. There was no coordination between the two entities.

The situation raises tensions between the Nation, which represents all Osage citizens, and the Minerals Council, which only represents headright holders.

“After we spent over a year in this effort, it was really disappointing to not have received the requested funds,” Revard said. “We did all the hard work and we didn’t get any. And the chief got twice as much as what we asked for.”

Without a well-plugging program of its own, the Osage government will have to start from scratch, organizing contractors and identifying high-risk wells just as the council has done previously.

Jim Gray, former chief of the Osage Nation, said the Nation’s environmental department would ideally work in tandem with the Minerals Council to get the job done. However, he acknowledged that rival interests between stakeholders complicate the prospects of such a collaboration.

“I would think everyone has a shared interest in a successful plugging of a well,” he said, “that no one is in dispute over whether or not it needs to be plugged. This shouldn’t even be an issue, should be just getting done.”

The history of the U.S. government’s attempt to impede tribal economic development is a long one. From limiting taxing authority to creating bureaucratic hurdles for businesses, federal and elected officials have restricted the ability of many tribes to freely build sustainable economies. Nowhere are those restrictions more apparent than in the federal government’s involvement with the Osage mineral estate.

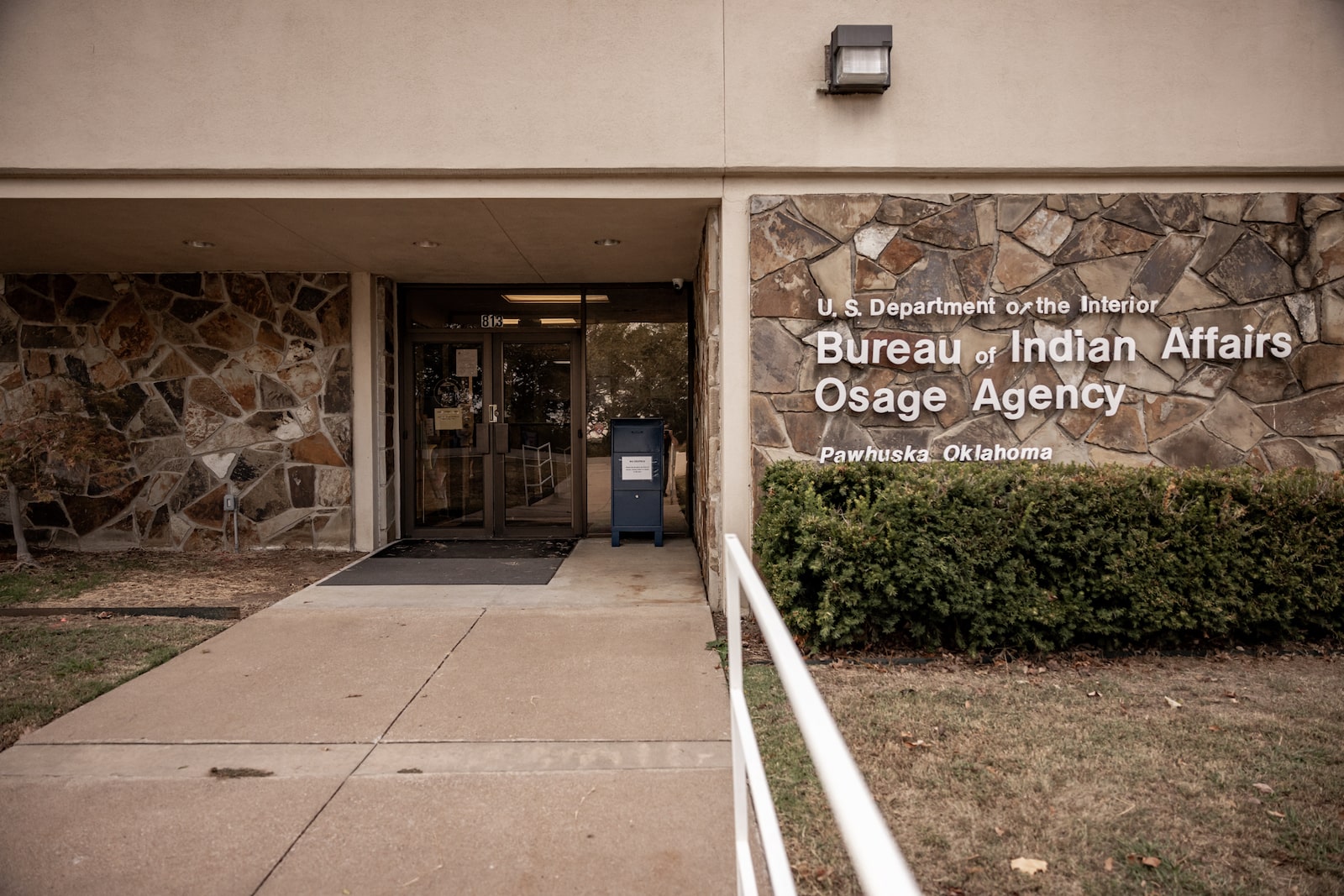

The Osage Nation purchased its own reservation in 1872 following the sale of many of its ancestral lands located in present-day Kansas. It’s the only tribe to buy its own reservation, but the 1906 law made the BIA — not the Osage Nation — manager of the day-to-day operation, use, and development of the oil and gas resources that belong to the tribe.

The Osage Nation purchased its own reservation — the only tribe to do so — but a 1906 law made the Bureau of Indian Affairs, not the Osage Nation, manager of the day-to-day operation, use, and development of the oil and gas resources that belong to the tribe. Shane Brown / Grist / Osage News

For decades, the federal government also only recognized those Osages with a headright. The thousands of headright-owning Osage members could vote in tribal elections and run for office, but Osages without a share in the mineral estate were denied those rights. It was a unique system even among tribal governments. To rectify the issue, the Osage peoples created a new government with executive, legislative, and judicial branches and ratified a constitution. Today, there are more than 25,000 enrolled Osage members.

For the Osage Nation, protecting the mineral estate has been a priority. Quarterly payments can be a lifeline for headright owners, and over the years, shareholders have accused the BIA of mismanaging the estate. Two decades ago, the Osage Nation sued the agency, claiming that it had failed to pay shareholders the highest posted price on oil and gas leases and allowed buyers to purchase oil up to $2.30 less per barrel. Over the decades, it meant shareholders had likely been shorted billions of dollars.

In 2011, the Nation won a historic $380 million settlement from the United States. As part of that settlement, the Department of the Interior and the BIA were required to work with the Minerals Council on new rules for oil and gas leasing in Osage.

But when the BIA began working on rules in 2013, it caused an exodus of oil and gas operators. The agency’s new proposal made turning a profit near impossible, companies claimed, and the uncertainty over the effects the rules would have led to their departure. In the wake of those rules, oil production declined and royalty payments plunged. In 2012, the payout for a headright was $40,800. By 2020, that figure had dropped to $10,400.

“We had clients abandon the entirety of Osage County” when the rules were proposed, said Trevor Henson, the oil and gas attorney. “From an operator standpoint, they were looking at the fact that they were going to have to comply with these new regulations, and they were going to be so costly that most of them couldn’t afford it, and they just said, ‘Look, I’ll go find a place to operate wells elsewhere.’ The end result is that the Osage mineral estate makes less money.”

Asked why headright payments have declined so dramatically, the BIA made no mention of its regulatory history or its management of Osage resources.

“As with any mineral estate, revenues from the Osage Mineral Estate are impacted by fluctuating energy prices around the world,” a spokesperson said in an email.

The BIA is now attempting to rewrite those rules for the second time. Earlier this year, the agency released a new proposal that increases royalty payments to the Osage Nation but does little to address the agency’s chronically inadequate bonding requirements for orphan wells. If enacted, the new rule would require operators to post bonds depending on well depth or the number of acres they drill on. This highest bond amount is still $150,000. While the new regulations are a slight improvement from current requirements, the agency’s own analysis of the proposal shows that it expects to collect at most $2.4 million in additional bonds over 20 years — enough to plug perhaps 100 wells.

“These proposed revisions secure this special trust asset of the Osage Nation for generations to come through accountability and best industry practices,” Assistant Secretary of the Interior Bryan Newland wrote in a statement.

The agency is keeping bonding levels low in part because of the new round of pushbacks it has received from oil and gas companies as well as the Osage Minerals Council, according to a member of the council. Similar to the changes that arrived a decade before, for companies operating on the margins more stringent bonding requirements can push their financials into the red. And if operators abandon the county and walk away from their environmental responsibilities, orphan well counts could balloon. Fewer operators and less drilling also mean lower royalty payments to the Osage headright owners.

The new rules have little support from tribal officials. At a meeting about the proposed regulations, Principal Chief Geoffrey Standing Bear told Osage News the federal government is stepping on the Nation’s toes.

“They are issuing regulations that are so inclusive of what I think is the Osage Minerals Council business,” Standing Bear said. “It’s like the federal government is showing everyone they don’t have faith in the capabilities of our Osage Minerals Council. I don’t see the federal government going to ConocoPhillips and telling them how to run their business.”

Gray, the former Osage Nation chief, also emphasized the need for the tribe to take the lead in managing the estate. The blame for the vast problem of abandoned oil wells on Osage land, he said, ultimately rests with the oil and gas operators who came to the county to extract fuel and left gaping holes in the earth. But in their absence, the burden falls on the Osage government to clean things up, he said. Gray described this duty as a kind of test, an opportunity for the Nation to demonstrate that the groups within its governance structure can put aside their disagreements for the betterment of its citizens. It’s easy to be on the same page about buying Osage land back from the federal government or applying for a grant to carry out a needed public service in the community, he said. It’s harder to make the right calls on more contentious issues like energy resources.

“There’s a maturation process that I think has to happen,” Gray said. “And the way to get to the other side is by exercising our responsibility as a sovereign nation, in a good way and responsible way in good times, but especially in bad times.”

The wells on the Roaches’ land are nearly 90 years old.

Nona Roach says that when McKee filed for bankruptcy, the company didn’t notify the Minerals Council and didn’t take steps to assess their wells — a critical step in the code of federal regulations and key to alerting the BIA on whether to keep the well in production or plug it.

The frustration is palpable. The Roaches say the BIA never sides with the landowner.

“That’s been the problem every time something would happen,” said Nona. “They would side with the operator because who’s making them the money: the operator.”

The couple say they know there’s a new regulation code in development, but they’re not optimistic: There are already laws in place that companies like McKee were supposed to follow. They just choose not to.

A representative with McKee could not be located for comment for this story.

“The whole thing comes down to this,” Nona said. “They already have the regulations and refuse to enforce them. They’re not going to enforce them any better if they have more of them. That’s the problem.”

The Roaches say they’ve had good oil producers on their land, people who clean up the mess, notify them when there is a saltwater leak, and maintain the roads. One producer even helped their cow give birth. Whether or not the new regulations will create an environment that encourages that neighborly attitude, however, and protect the land from orphan wells, the Roaches say they’ll wait and see.

“I think they just really need to just treat our land like it’s theirs,” said Nona. “Not come in here and pollute and just destroy everything they touch.”