In 1989, just as leaders around the world were starting to think seriously about tackling global warming, the National Association of Manufacturers assembled a group of corporations — utilities, oil companies, automakers, and more — united by one thing: They wanted to stop climate action. It was called, in Orwellian fashion, the Global Climate Coalition.

With 79 members at its height in 1991, the coalition helped lay the groundwork for efforts to delay action on climate change for decades to come. It would not just deny the science, but also argue that shifting away from fossil fuels would hurt the economy and the American way of life. The coalition lobbied key politicians, developed a robust public relations campaign, and gave industry a voice in international climate negotiations, all to derail efforts to limit carbon emissions. Its arguments were so successful that they’re still employed today, or, more perniciously, simply taken for granted.

“This was all developed in the 1990s, and we can prove it,” said Robert Brulle, a sociologist at Brown University. In a new paper published in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Politics, Brulle details the untold history of corporate America’s earliest efforts to block climate legislation, supported by recently uncovered documents.

Based on conversations with lawyers, Brulle believes his report could be helpful in lawsuits to hold corporations responsible for heating up the planet. “It would be used to basically document that this has been a long-term, corporate objective and that they should be held liable for the damages — that their political actions resulted in the fact that we didn’t deal with climate change,” he said.

Before the Global Climate Coalition formed in 1989, chemical companies had been ordered to phase out substances that were damaging the ozone layer under the Montreal Protocol, signed by the United States in 1987. They hoped to avoid a repeat with carbon dioxide. In the summer of 1988, James Hansen, then the NASA Administrator, had testified before Congress, raising the alarm that the “greenhouse effect” was already having discernible effects, with much worse to come.

The Global Climate Coalition wasn’t the only organization trying to thwart climate action in the late 1980s. There was the similarly named Global Climate Council and the International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association led by Exxon — but it was the first and largest to do so. The coalition included oil giants like Shell and Chevron as well as other companies that had a stake in keeping fossil fuels alive, such as the railroads that transported coal and the steelmakers that used it in production. Utilities like Duke Power Company were heavily dependent on coal and made up the biggest share of members. General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler manufactured internal combustion engines that ran on petroleum, so they joined the coalition, too. The roster also included the National Mining Association, Dow Chemical Company, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

A newly unearthed, undated document from E. Bruce Harrison — a public relations expert who helped the coalition tailor its messages to avoid environmental regulations — describes how the Global Climate Coalition’s “aggressive campaign” influenced the debate and watered down policies. Brulle calls it a “brag sheet.”

“GCC has successfully turned the tide on press coverage of global climate change science, effectively countering the ecocatastrophe message and asserting the lack of scientific consensus on global warming,” Harrison wrote.

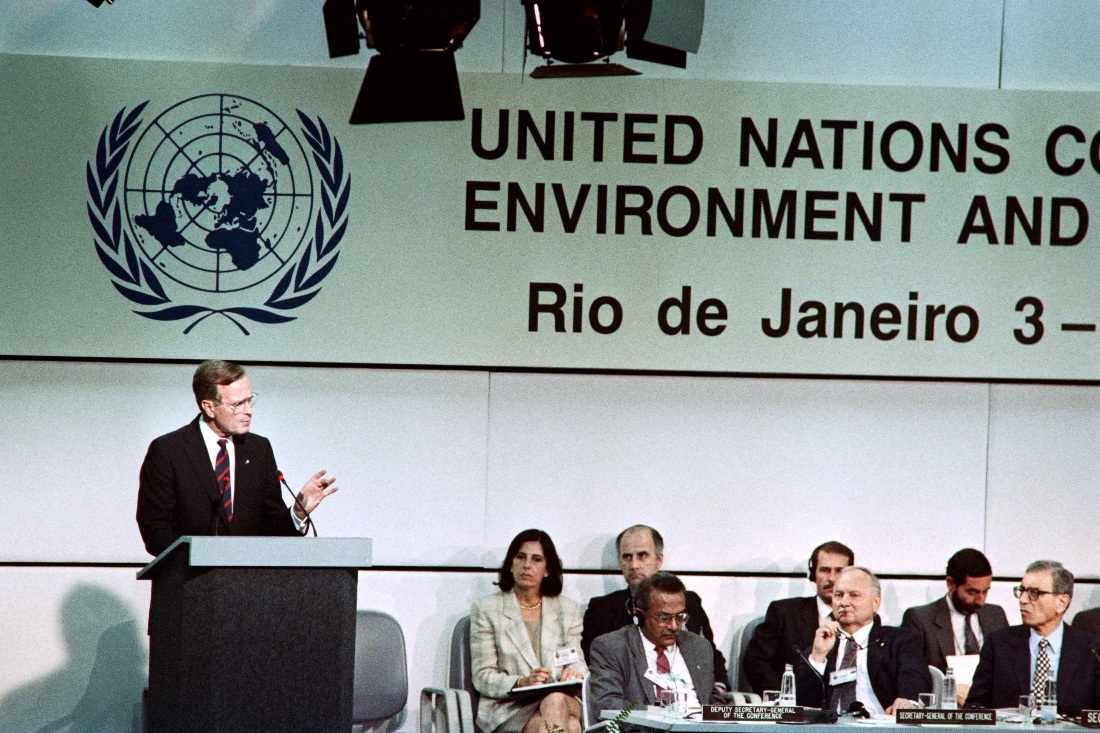

He claimed that the coalition had “actively influenced” congressional debates over carbon taxes to avoid “strict energy taxes,” and had affected the Clinton administration’s decision “to rely on voluntary (rather than mandatory) measures” to reduce emissions in its 1993 National Action Plan, required under an international climate treaty hashed out in Rio de Janeiro the year before. The Global Climate Coalition had influenced the Rio treaty, too — a National Association of Manufacturers business activity report in 1992 congratulated itself on a “strong and effective presence” during the Rio negotiations and celebrated that the final product did not include binding emissions reductions.

The new documents show how close the international community came to regulating carbon emissions. At the first Conference of Parties in Berlin in 1995, for instance, world leaders agreed to institute mandatory emissions requirements in two years. Corporations saw this as an impending disaster. “Dozens of UN agencies, international organizations and environmental special interest groups are driving events — regardless of economic costs and remaining scientific uncertainties — toward a conclusion that is inimical to the interests of the GCC and the U.S. economy,” read the coalition’s communications plan for 1994-1995.

In 1997, the coalition worked with Senators Robert Byrd, a Democrat from West Virginia, and Chuck Hagel, a Republican from Nebraska, to pass an amendment setting strict criteria for an international climate accord. The Senate unanimously supported the resolution, which stipulated that any agreement would need to include emissions reductions from developing countries (a nonstarter for international negotiations) and could not cause serious harm to the U.S. economy. It was essentially a rejection of the Kyoto Protocol, which would have required countries to cut carbon emissions to 5 percent below 1990 levels by 2012. The treaty was signed by President Bill Clinton in 1997, but the Senate refused to ratify it, and President George W. Bush withdrew from the accord after he took office in 2001.

A few months later, White House staff met with the Global Climate Coalition and congratulated the corporate group. “POTUS rejected Kyoto, in part, based on input from you,” said the talking points prepared for Paula Dobriansky, at the time the Under Secretary of State for Global Affairs and the lead negotiator on U.S. climate policy. Its mission accomplished, the Global Climate Coalition disbanded in 2002.

“This is a really skillfully executed public relations and influence campaign that ran a good 12 years, and it achieved enormous success,” Brulle said. “And it set a template for how to do this, and how to win, on climate change.” The coalition accomplished all this on a budget of between $500,000 and $2 million a year.

Part of the strategy was to emphasize the economic cost of acting on climate change without the broader context. In 1989, the first year of its existence, the Global Climate Coalition commissioned an economic analysis that calculated that cutting carbon emissions 20 percent within a decade would push up Americans’ power bills by 15 percent. It was the start of a tried-and-true approach to blocking restrictions on carbon emissions by exaggerating upfront costs: a calculus that ignores the health benefits, as well as the long-term savings of not turning the planet into an oven.

Similar arguments are still stalling climate legislation today. Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, a Democrat, has said he can’t support Build Back Better, President Joe Biden’s package of climate and social policy programs because of the trillion-dollar sticker price. This narrow kind of economic analysis of costs and benefits has become the dominant way politicians assess climate policy. “Only now are we starting to show its historical basis as a kind of a rhetoric to counter environmentalism,” Brulle said.

The Global Climate Coalition was also an early adopter of what has been called the “China excuse” — the idea that the United States, the world’s largest historic emitter of carbon dioxide, shouldn’t cut emissions unless developing countries like China and India did too. The coalition used this argument as far back as 1990, when it argued during a congressional testimony that any global agreement should require developing countries to reduce emissions.

Another element of the Global Climate Coalition’s messaging strategy was to paint fossil fuels as a symbol of abundance, integral to the American way of life. While the coalition was working to derail the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, it put out an advertisement with a large photo of smiling children alongside the line “Don’t risk our economic future.” It warned that signing the global agreement “would force American families to restrict our use of the oil, gasoline, and electricity — that heats and cools homes and schools, gets us to our jobs, and runs our factories and businesses.”

It’s similar to a recent ad from Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind the Dakota Access pipeline. The commercial follows two people getting ready for a date and meeting outside a bar — and then rewinds the whole thing, missing key elements. “That connection was brought to you by petroleum products,” a man says. “But what if we lived in a world without oil and natural gas?” With a poof, hair gel disappears, contacts fade away, and the frame of the car hits the cement without its tires. On the game playing on a screen behind the couple in the restaurant, the football vanishes a second before getting kicked.

Such advertisements could be considered the legacy of the Global Climate Coalition. “When you look at the propaganda and the amount of studies that they put in, yeah, they attack science,” Brulle said, “but I think they did a lot more talking about the economic impacts and the threats to the American way of life that all of this represented.”