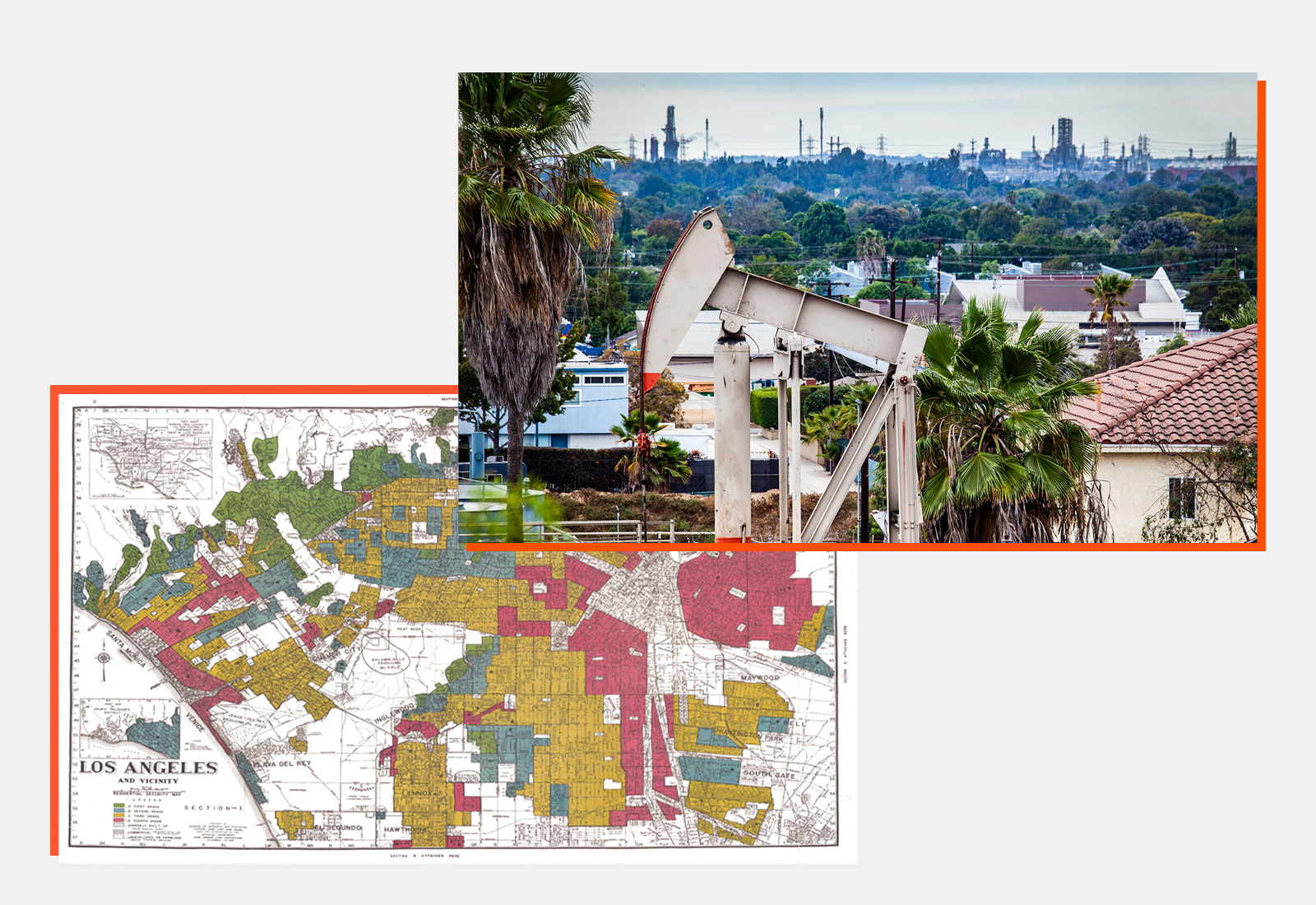

Neighborhoods that were redlined have nearly twice as many oil and gas wells as neighborhoods that were historically considered “desirable,” a new study has found. The findings underscore the connection between structural racism and polluting oil and gas infrastructure.

The analysis is the first of its kind, the work of researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, the University of California, San Francisco, and Columbia University. They compared data on the location of plugged and active oil and gas wells to data from maps generated by the Home Owners Loan Corporation, the federal lending program created to prevent home foreclosures during the Great Depression. The program excluded Black people — as well as Jews, other people of color, and immigrants — from opportunities by creating maps which labeled white neighborhoods as “desirable,” shading them green, and labeled Black neighborhoods, in particular, as “hazardous,” shading them red — hence the term “redlining.”

Looking at data for 33 cities where oil and gas wells are drilled and operated in urban neighborhoods across 13 states, researchers discovered the striking correlation between neighborhoods that were redlined and neighborhoods that have a high density of oil and gas wells.

This new analysis “clarifies the role of systemic environmental racism in creating disparities,” said Kyle Ferrar, a program director with FracTracker, a group that provides data on the health effects of oil and gas development.

“We know from other work that marginalized people — especially Black people, Latinx people, and low-income people — are more likely to live near oil and gas wells,” said David J.X. Gonzalez, lead author of the study. “But we don’t know the processes that lead to these disparities, and I think it’s really important that we understand those.”

To better understand those processes, Gonzalez and his colleagues also investigated whether redlining made a community more likely to have new wells drilled and operated near where people live. While they did not have enough data to prove a causal relationship, “we’re seeing a signal that redlining may have been part of why some neighborhoods had more wells compared to similar neighborhoods that weren’t redlined,” said Gonzalez.

Oil and gas wells release a slew of air pollutants, including volatile organic compounds, smog-forming compounds, and fine particulate matter. Numerous studies have found that living near oil and gas wells increases a person’s risk of cardiovascular disease, impaired lung function, anxiety, depression, preterm birth, and impaired fetal growth — serious concerns for the estimated 17 million people in the U.S. who live within a mile of at least one active well.

It’s not news that redlined communities tend to experience worse health outcomes. There are also links between neighborhoods that have undergone disinvestment and neighborhoods where there are higher rates of gun violence and less green space. But, said Gonzalez, “it’s important to consider the historical, racist policies that have led to disparities, and why we’re seeing worse health outcomes in these historically-redlined neighborhoods.”