Nearly two dozen lawsuits filed by cities and states aim to put fossil fuel companies on trial for deceiving the public about climate change. But they’ve been stuck in legal limbo for half a decade, with companies deploying several maneuvers to block them. Now a surprising source has unleashed those lawsuits: the conservative-dominated Supreme Court.

On Monday, the justices rejected petitions from Chevron, Shell, BP, and other oil companies to move these cases from the state courts where they were filed to federal courts, an arena considered more friendly to the industry. The Supreme Court’s rejection brings an end to a long jurisdictional battle, meaning that cases in Colorado, Maryland, California, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and more can finally proceed — potentially toward jury trials.

“It’s the industry’s worst nightmare to have to explain their lies in front of a jury,” said Richard Wiles, president of The Center for Climate Integrity, an environmental advocacy organization.

The wave of lawsuits began in 2017, when cities and counties in California sued an array of oil, gas, and coal companies using state consumer protection laws that prohibit deceptive advertising. The lawsuits were set in motion by revelations that ExxonMobil had known about the dangers of burning fossil fuels since 1977, but publicly cast doubt on the science and worked to block legislation to restrict carbon pollution.

Oil companies have tried to shuffle these lawsuits to federal courts for years, arguing that they weren’t really about consumer protection laws, but the broader matter of climate change, a federal concern. Judge after judge dismissed this line of reasoning, until it went all the way to the Supreme Court. Last month, the Biden administration urged the court to leave these lawsuits to the states — exactly what it ended up doing.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh wanted to hear an argument from ExxonMobil and Suncor Energy, according to the order list the court released on Monday, but there weren’t enough justices on his side. Justice Samuel Alito recused himself from the decision for unstated reasons, though some have noted he owns stock in Phillips 66 and ConocoPhillips, among the fossil fuel companies pushing to move these cases to federal courts.

“After almost six years, things are finally about to get interesting,” said Karen Sokol, a law professor at Loyola University in New Orleans. These procedural battles weren’t just time-consuming — they were also kind of boring. The media and the public simply aren’t captivated by the esoteric debate over whether a case belongs in federal or state courts, Sokol said.

Industry groups lamented the Supreme Court’s decision. An attorney for Chevron told Reuters he was still confident that the cases would ultimately be dismissed in state court because the magnitude of the issue required a federal response. A lawyer with the National Association of Manufacturers’ legal arm said that the Supreme Court’s move risks creating a “patchwork of state court approaches to important public policy matters that are inherently federal and global in nature.”

If anything, the long waiting period has strengthened the case against oil companies, with recent revelations bolstering the argument that they understood the science behind climate change but told the public something else. A study earlier this year found that Exxon’s internal scientists predicted climate change with startling accuracy 40 years ago by quantifying how their projections matched up with real-world temperature changes. In recent months, a congressional investigation into the fossil fuel industry’s role in misleading the public about climate change released hundreds of pages of subpoenaed documents. An internal email from a Shell employee in 2020, for example, said that the company’s public promotion of a path toward zeroing out its carbon emissions “has nothing to do with our business plans.”

And now that the court cases can finally proceed, more evidence is likely to be uncovered. The next major step before a trial is “discovery,” in which both sides try to uncover evidence that could help make their case in court. It could unearth new documents related to what oil companies learned from their in-house scientists and to what extent executives suppressed that information or misrepresented it publicly. Industry employees could also be called in to answer questions.

“The discovery system is quite powerful in terms of unveiling hidden information,” more powerful than some federal agencies, Sokol said. A lot of what the public learned about the tobacco industry’s effort to cover up the link between lung cancer and smoking, for example, came out of the discovery process. Tobacco companies paid hundreds of billions of dollars in settlements.

It’s not a guarantee that the public will be able to see these documents or transcripts from witnesses in the climate cases, however. The industry might argue that the information is a “trade secret,” Wiles said. Judges get to decide what evidence gets released.

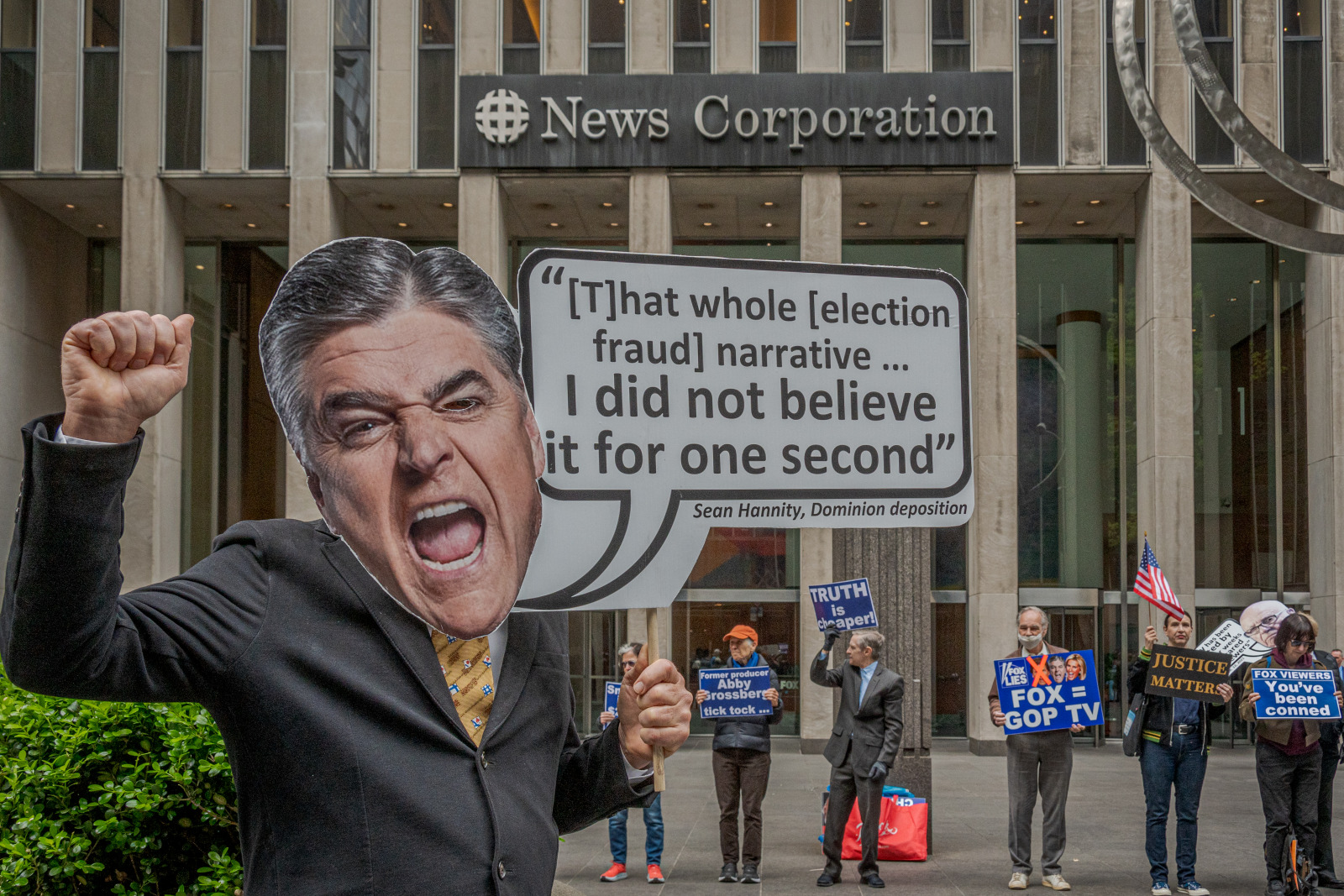

Documents might come out in a slow drip, with lawyers attaching them to their arguments as supporting evidence, Wiles said, but there’s a chance they could be released all at once. In the recent Dominion Voting Systems lawsuit accusing Fox News of defamation, for instance, the judge released hundreds of pages of documents in the public interest, showing that the media company’s staff privately derided conspiracy theories about the 2020 election while promoting them on air. If oil companies decide to settle the consumer protection cases before going to trial, one stipulation might be that documents be made public, as was required by settlements for tobacco and opioid lawsuits.

The discovery process could take a while — and there are still plenty of ways oil companies could draw these cases out — but eventually, they could wind up in front of juries, where oil companies will have to defend a well-documented trail of deception in front of real people. And with these cases all unfolding in different state courts, the industry will have to fight each battle separately. “We only have to win in a couple to really get somewhere,” Wiles said, referring to the cities and states suing oil companies. “They basically have to win everywhere.”