This story was originally published by LAist and is republished with permission.

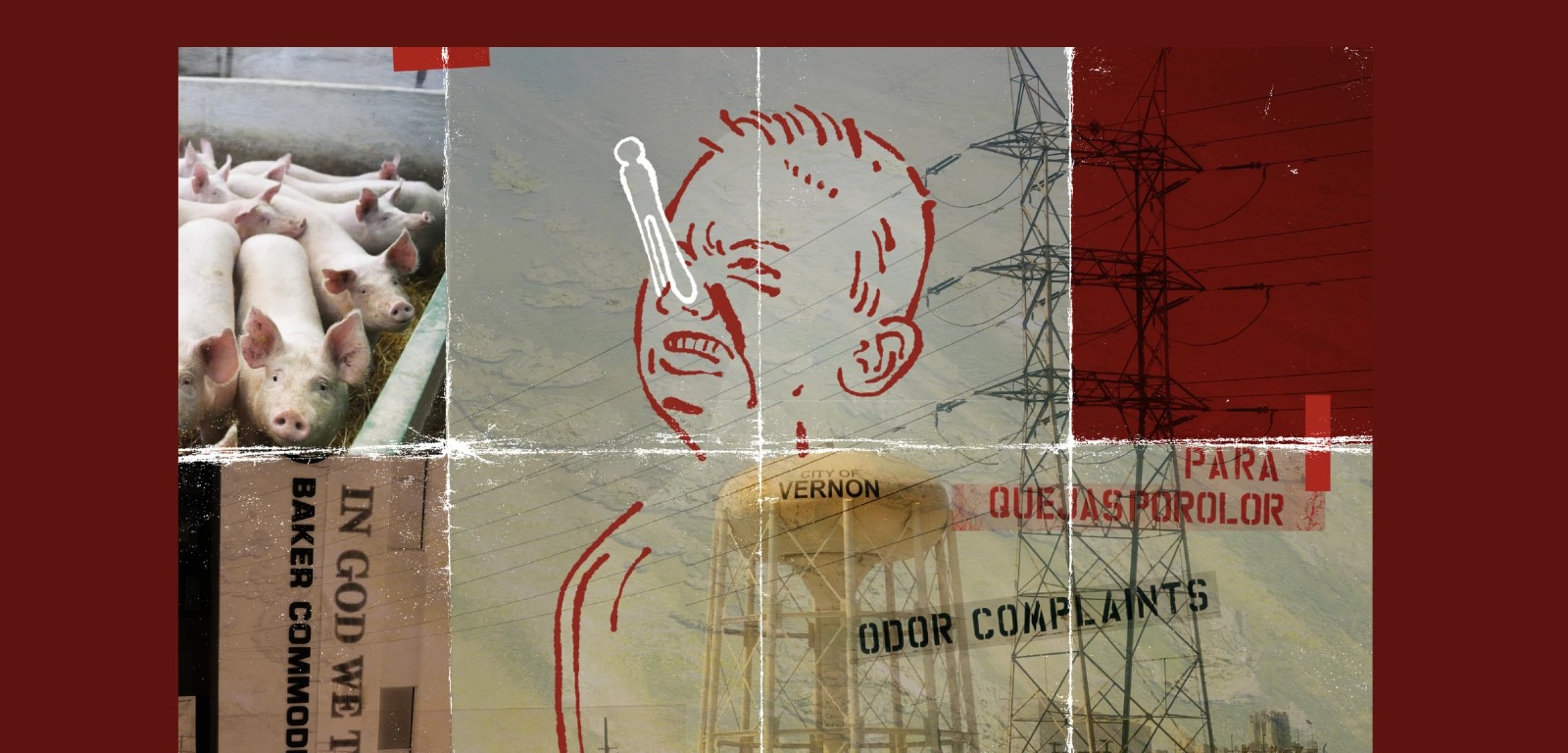

Tucked along Bandini Boulevard in the city of Vernon are the headquarters for Baker Commodities Inc., a company that employs 900 workers across the U.S. and is home base for some of the grisliest industrial work in the country.

Behind the nondescript walls of its campus along the L.A. River sit machines used to grind, cook, and press leftover pieces of cows, pigs, and chickens. These remains — and, sometimes, entire carcasses — are delivered on semitrucks from butcher shops, grocery stores, restaurants, slaughterhouses and livestock farms. A worker then pushes them into a pit with a tractor and, through a process called rendering, they’re turned into fats, meat and bone meal, and hides.

These materials are recycled to make scores of everyday products, including soap, pet food, makeup, and leather goods. The long-running industry plays important roles in reducing food waste.

For decades, residents in surrounding neighborhoods have complained of putrid dead animal smells. In 2017, community pressure compelled the local agency that oversees air emissions, the South Coast Air Quality Management District (AQMD), to adopt a rule to mitigate odors from Baker and a handful of other rendering plants. Among other requirements, the rule forces these companies to post signs indicating where residents can report odor issues — a demand some plants lobbied against. Then, in September 2022, the agency shut down Baker, citing repeat violations of its odor mitigation rule.

At the time, community members and elected officials celebrated the closure as a win. But what many don’t know is that the company has partially reopened and is waging an intense legal battle against AQMD. After AQMD shut it down, Baker filed a lawsuit against the AQMD in L.A. County Superior Court. Baker claims the company was not in violation of the odor mitigation rule and that it was treated unfairly. Baker also demands that the shutdown order be tossed out and aims to bar air regulators from shutting it down in the future.

LAist spoke with dozens of local residents and reviewed odor complaint records, violation records, notices to comply, and inspection reports to piece together how the rendering of dead animals at Baker has impacted surrounding communities.

We found that since the odor mitigation rule went into effect in 2017, AQMD has issued 12 violations and five notices to comply to Baker. Eight of them were for violating the odor mitigation rule. The rest were for failing to comply with permit conditions and other requirements. Three of the violations are still pending.

LAist also found 111 odor complaints identified by the person reporting the smell or by AQMD as being tied to Baker between August 2019 and late last week. These complaints came from homes, local schools, and businesses near Baker’s headquarters.

In addition, Baker failed to store animal remains within four hours of delivery, leaving them out to fester and violating AQMD’s rules, according to the agency’s attorneys — and it did so six times between August 2019 and January 2022. An AQMD inspector reported Baker violated AQMD rules that require surfaces exposed to animal matter to be washed down at least once per working day, according to his sworn written statement filed in Baker’s court case. The inspector said he saw strings of animal matter dangling on grates at the company’s headquarters.

Plus, in Baker’s unloading zone for animal remains, broken concrete or asphalt was present in March and April 2022, according to AQMD’s attorneys — a problem that officials at the agency say can cause water to pool and smells to fester.

We should note that Baker has disputed AQMD findings in the latter three items in court filings.

In the year since AQMD ordered Baker to shut down, residents say the odors are less intense and less frequent — and AQMD complaint records associated with the company show a dramatic drop in reported smell problems. The shutdown lasted nearly nine months, until the company petitioned the hearing board and was granted permission to work in a limited capacity, doing trap grease and wastewater treatment — but not rendering animals.

Many community members were worried to learn from LAist that the court may allow the company to fully reopen and return to rendering livestock and poultry without making long-term changes to the way they operate.

A long track record of problems, a fierce fight to stay in business

A review by LAist also uncovered details of the steps Baker has taken to try to get back to running at full scale in Vernon. The rendering company submitted 125 legal filings in its battle against AQMD over a 12-month period, arguing that it’s in compliance with the odor mitigation rule. In that time, it’s had two law firms working the case, which calls for $200 million in damages from the government agency for lost revenue, the disclosure of trade secrets and other items. Its current legal team at DLA Piper — a top-ranking, multinational law firm — includes Angela Agrusa, who specializes in brand-crisis litigation and has represented comedian and actor Bill Cosby and Chipotle, among others.

“The fact that Baker Commodities would come at an agency that is really intended to protect the public’s health is not just unfortunate, but it is despicable,” said Angelo Logan, who grew up in the nearby city of Commerce and returns weekly to visit his mother. Logan currently serves on the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council and learned of the litigation from LAist.

Cudahy Councilmember Elizabeth Alcantar, who lives about 3 miles away from Baker, was also unaware of the legal fight until LAist’s reporting.

“It’s absolutely concerning to see that happen,” she said.

Alcantar grew up in Cudahy and says she and her family have endured the stench of rotting flesh for as long as she can remember. She was shocked to hear Baker is pursuing legal action that will cost taxpayers money, instead of addressing community concerns.

“It’s going to take AQMD’s time and funds away from what they should be doing, which is enforcement,” Alcantar said of the litigation, explaining that the community has been under duress for years due to foul odors. “[W]e are here, simply wanting to breathe clean air.”

Baker’s assistant vice president of public relations and legislative affairs, Jimmy Andreoli II, declined multiple interview requests. Agrusa, Baker’s lead attorney, did not respond to our requests for comment.

In an emailed statement Andreoli said, “While we cannot comment on active litigation, we are dedicated to finding sustainable ways to support California’s food production and restaurant industries with continued strict adherence to local, state, and federal environmental laws.”

“Some of our business operations have been approved to resume,” said Andreoli, who is the grandson of Baker’s 96-year-old CEO, James Andreoli. Jimmy Andreoli II added that they look forward to finding long-term solutions with AQMD.

Baker’s lawsuit against AQMD is still pending. Later this month, if a settlement isn’t reached beforehand, an L.A. Superior Court judge is scheduled to decide whether the rendering company can reopen at full capacity. The judge will also rule on the $200 million in damages Baker is seeking, as well as its call to keep AQMD from shutting it down in the future.

If Baker succeeds in court, interviews with community members suggest it could further erode the relationship between the city of Vernon and local residents across Southeast L.A., many of whom are grappling with odors on top of other environmental issues.

A company with big problems

Many people who live in or near Vernon have no idea that they live close to four rendering plants that process everything from fat, to livestock, to the remains of cats and dogs. The city, which is just 5 square miles in size, is also home to at least 40 meat processors, which buy meat from slaughterhouses to prepare items found at grocery stores, like sausages and steaks. There are also six slaughterhouses within 1 mile of Vernon’s city limits.

At some places, silos and smokestacks hint at what’s happening inside, along with flocks of seagulls hovering far from shore. But, for the most part, these businesses are tucked behind bland metal sheets and concrete walls.

Baker itself is sandwiched between the L.A. River and several train tracks. The rendering company has been in Vernon since the 1940s. But after AQMD determined that Baker blew a deadline to seal off its rendering operations to keep potential odors from escaping in spring 2022, the agency’s legal counsel moved to shut it down.

AQMD’s hearing board, which enforces the agency’s regulations, gathered to vote on the shutdown in September of 2022. Before reaching a decision, the board held a hearing, which LAist found little media coverage of at the time. It provided a rare look inside Baker’s headquarters.

Over a span of three days via Zoom, attorneys for both parties peppered an AQMD inspector with questions.

In 2022 inspector Dillon Harris testified that he visited Baker nine times. He documented hooves and other animal bones strewn across the floor, overflowing from a large trash bin. He spotted a trough with built up blood, animal fat, and wastewater. He said he saw staff dumping sludge — a thick, pancake batter-like mix of liquid and solid animal remains — from trucks into open-air pits. Baker, he said, also left equipment doors and panels open, which are supposed to be kept shut to trap possible smells, and employees dumped expired clams, shrimp and ground beef into an exposed container.

During the hearing, dozens of photographs capture Baker’s facility.

[Caution: these links go to images of the photos displayed on video in hearings]

In them, rib cages can be seen among a heap of animal parts, pools of blood-colored liquid are shown in multiple locations, a drain is backed up and surrounded by dead animal debris. Harris, the inspector, also captured images of raw animal material leaking out of the rendering equipment. Baker has argued that photos shown during the hearing should be sealed from the public’s view because they contain trade secrets that competitors can now access.

The Andreoli family, which has owned Baker since the 1980s, spoke at the hearing and disputed Harris’ findings. Jimmy Andreoli II said he visited the Vernon facility a week earlier and saw “a wash truck that was moving throughout the facility and washing down various roadway surfaces.”

Baker attributed some of the inspector’s findings to human error. Jason Andreoli, who was identified at the hearing as Baker’s general manager, said the company put up signs reminding staff to keep the doors closed. “And we also put a policy in place that if they are left open, there’s gonna be disciplinary action,” he said.

Several hearing board members appeared mystified by Baker’s claims that the company was in compliance with AQMD rules.

“Every picture virtually that we see is of equipment that is absolutely filthy,” said the late Dr. Allan Bernstein, one of the hearing board’s voting members who died last spring.

“It’s mind-boggling to sit here and see anyone try to defend this position when we’re all looking at these pictures with our eyes,” he added.

During closing statements, AQMD attorney Daphne Hsu said she understood the magnitude of shutting down the company. “We don’t ask a facility to stop operating lightly,” she said, noting Baker could have proposed a timeline to come into compliance. Instead, she said, the company chose to dispute the agency’s findings.

“Baker must be in compliance before it restarts,” Hsu added. “The community has waited long enough.”

The hearing board voted 4 to 1 to shut down Baker. That’s when the court battle began.

‘I had to step away because I almost vomited’

When AQMD implemented the odor mitigation rule in November 2017, rendering facilities that had to comply were given 90 days to meet basic standards. The goal of the rule was straightforward: to keep potential odor sources contained and protect people living nearby. The rule requires steps like washing down surfaces at least once a day and repairing cracks in the asphalt to keep pools of odorous bacteria from forming.

“As they’re bulldozing and pushing all these raw carcasses, [the animal remains get] smeared across asphalt and concrete, and odors start developing,” explained Wayne Nastri, AQMD’s executive officer, in an interview with LAist. “What the rule actually intended to do was to control the process the whole way, to minimize [animal remains’] exposure to the air that would generate those kinds of odors.”

AQMD gave renderers subject to the rule up to three and a half years to install enclosures, or bring all their operations into a closed system indoors, to keep odors from drifting off site. Some asked for extensions before they finished the work, but, according to AQMD, Baker is the only one that has not complied. In its lawsuit, Baker repeatedly argues it is in compliance.

When Harris, the AQMD inspector, checked out Baker for the first time after the rule went into effect in 2018, he remembers being disgusted.

“I had to step away because I almost vomited,” he said in a sworn written statement filed with AQMD’s response to Baker’s lawsuit.

Recalling the inspections he conducted at Baker in 2022, Harris added that: “The odor at the facility smells intensely of rotting animals.”

His work boots, he explained, were so soaked through with the smell of rendering that he couldn’t use them at non-rendering facilities. In one of Baker’s rendering plants at its Vernon campus, he said “rotting odor emanates from all sides.”

L.A. County Supervisor Janice Hahn’s district includes Vernon — she advocated last year for Baker’s shutdown.

“It was clear that Baker Commodities had long violated air quality rules and had done little to nothing to come into compliance,” she said in an emailed response to questions from LAist. “It was time for [AQMD] to uphold the rules they had on the books and protect the community from this company.”

Nastri, AQMD’s executive officer, declined to speak on Baker’s lawsuit, citing pending litigation. Court filings show AQMD has hired two outside law firms to work the case, in addition to the agency’s in-house attorneys. They’ve filed a cross-complaint against Baker, demanding that the rendering company pay $10,000 per day for each of its violations.

Nastri confirmed to LAist that Baker has committed the most violations out of any of the rendering plants in its jurisdiction.

The air pollution agency’s rules “are there to ensure that we have a level playing field,” Nastri said. “And to all those companies that are making the investments, that are operating in conditions that they’re supposed to operate, it’s unfair if we were to let others who do not make those investments and seek to profit off of the lack of compliance — that’s just wrong.”

“We are very consistent and very strong in our enforcement approach,” he added. “And so long as those companies continue to violate those rules or regulations, we will go after them. Period.”

How odors impact community members’ daily lives

Residents of Southeast L.A. County, as well as Boyle Heights and unincorporated East L.A., have put up with rendering plant odors for years. And Baker is not alone — odor complaint records reviewed by LAist show the three other nearby rendering plants have also generated concerns.

So have other businesses. The city of Vernon is home to just 222 residents and is almost exclusively industrial — nearly 600 of its businesses handle or store hazardous chemicals, according to a city report. Local residents have lodged complaints with AQMD about strong garbage odors from trash collection companies, as well as nauseatingly sweet smells from flavor and fragrance suppliers. One resident complained their neighborhood reeked of “melting Jolly Ranchers.”

Shifting wind patterns near Vernon add to the challenges. According to Terrence Mann, AQMD’s deputy executive officer of compliance and enforcement, an odor can start off in Monterey Park, “then, just a few minutes later,” pop up in Huntington Park — about 11 miles away.

Interviews with local residents , as well as odor complaint data obtained through public records requests, show that people living in the area encounter the smells at dinner time; on their way to school; at work; on the playground; and during class.

Sometimes the stench comes and goes. But sometimes it persists for hours, or even several days. When it’s especially pungent, it can be stomach-churning. Community members also report getting headaches, as well as an itchy, burning sensation in their eyes and throats.

In interviews with LAist, affected residents often used phrases like “dead animal” or “rotting carcass” to describe these odors. Still, most of them have no idea where the stench comes from. Some local residents who’ve driven in Vernon past the now-shuttered Farmer John slaughterhouse, which is renowned for its pig murals, told LAist they’d always assumed the smell was coming from there.

“It wasn’t just that there was a smell — we all live in cities [that] have smells — it’s that it was a stench,” said Jackie Goldberg, Los Angeles Unified School District’s school board president. She fielded complaints from teachers and parents at schools near Baker and joined other elected officials in a letter demanding that rendering plants take greater accountability for odors in January 2022.

The smell was so bad it made it impossible to get through the day’s lessons, she said. Students were putting their heads down, asking to go home.

“It impacts your body,” she added. “You feel it in your eyes, you feel it in your throat, you smell it, you get headaches, your eyes burn. It’s not good for you, and it’s not good for kids in particular.”

In the months leading up to AQMD’s shutdown action, former state Assemblymember Cristina Garcia wrote her own letter to the agency, detailing her experience teaching math at Huntington Park High School in the ‘90s and early 2000s.

“The smell is so strong, putrid, and nauseating that my students could not focus,” she wrote. “[A]nd now, 20 years later, it is insulting that we are still dealing with the same problem.”

Without working air conditioning in her classroom, Garcia had to choose between shutting the door and windows to keep the odors out, or letting the stench in to get some ventilation. “And the hotter it got, the worse that smell would get,” she told LAist. “It was a constant struggle.”

Baker’s lawsuit was news to Garcia when she found out about it from LAist, but not a surprise. She said communities in Southeast L.A. have long been plagued by environmental justice issues and recalled that the now-shuttered Exide battery recycling plant spewed lead in the area for decades, then had its bankruptcy case settled in federal court.

“[Baker feels] that they could win and they could squeeze the agency on behalf of their bottom line, instead of on behalf of the public,” she said.

Dora Gómez and her two children have lived in the city of Vernon for eight years in an affordable housing complex built on land donated by the city. Gómez said the smells have been a persistent issue. When they occur, she shuts her windows and avoids going outdoors. She also bought an air purifier and has routinely purchased scented wax melts to ward off the stench.

Gómez had no idea four rendering plants circle her home in a 4-mile radius. She said she often thinks about leaving the area, but she pays less than $1,500 per month for a two-bedroom apartment and the rents in surrounding neighborhoods are not within her budget.

“It’s not a great place to raise your kids,” said Gómez, who said she worries about health effects from Exide in addition to the smell problems. Her apartment building has been flagged by the state Department of Toxic Substances Control for soil remediation after contamination from the battery recycling plant. “They’ve already been exposed to lead for all these years, it just makes you think like, you know, what else is in the air?

Maria Monares has lived in East Los Angeles, about 3 miles north of Baker’s pressers and grinders, for over three decades. Her children, who are now grown, attended Eastman Avenue Elementary School, just across the street from their home. Monares’ neighborhood has also been subject to rendering plant odors, a “horrible smell” that she compares to the stench of “death” and “burning bones.”

Aside from being unpleasant, the odors can be embarrassing, she said. Sometimes, the stench rolls in when she has company. Visitors will scrunch their faces in disgust and ask: ‘What is that?’

Over the years, Monares and her husband have lodged multiple complaints to AQMD. In some cases, the agency has sent inspectors out to her home. They’ve come, smelled what she’s smelling, asked questions, and taken notes. Then, the air quality got better. And when the odors returned, she and her husband got back on the phone.

“Us calling and bugging, hopefully it helps,” she said.

Businesses near Baker have also filed odor complaints with AQMD. Public records reviewed by LAist show that one company described a “horrible, putrid smell” that they said was coming from Baker. The “smell penetrates into our facility and many employees complain … Some feel nauseous,” it added.

But pinpointing an odor’s source can be difficult.

“The biggest challenge is that all of [the rendering companies] are located in close proximity to each other,” said Mann, with AQMD. “That’s part of the reason why our agency took the lead and created [the odor mitigation rule implemented in 2017],” he said, explaining that the agency now aims to proactively identify violations at rendering companies instead of waiting for complaints to come in before it takes action.

Nastri, AQMD’s executive officer, noted that, in recent years, there’s been an overall drop in odor complaints associated with rendering plants in the region. In 2021, he said, AQMD received nearly 400 complaints. As of Oct. 2, the agency reported 84 complaints so far this year.

Still, he added, “success would be the ultimate elimination of those complaints.”

Rendering’s role in mitigating climate change

Agriculture industry experts agree that rendering plays an important role in reducing waste. Humans don’t eat every part of the animals they consume, so “a tremendous volume of unused animal meat gets left over from our livestock and our poultry operations,” said Christine Birdsong, undersecretary at the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

By repurposing animal remains — like using fats for biodiesel, instead of extracting carbon from fossil fuels — renderers across the country “reclaim the carbon” from 56 billion pounds of unused animal parts each year, Birdsong added. Renderers also minimize waste by transforming those remains into a myriad of “really valuable ingredients” used in everything down to the gelatin casings of medicine capsules, she said.

“I have never seen any other industry that is more involved in recycling,” said Frank Mitloehner, a professor and air quality specialist at UC Davis’ animal science department. “I mean, literally, nothing goes to waste.”

Mitloehner said rendering plants are especially significant when livestock farms experience mass die-offs, often due to the spread of disease or extreme heat. “You’re not allowed to compost [animals], you’re not allowed to burn them. There’s no other way of dealing with that,” he said.

“Thank God we have people to work in [rendering plants],” Mitloehner added. “Because if we didn’t, we would have a serious disposal issue.”

Some community members frustrated with rendering odors don’t dispute the importance of the recycling work that’s done at Baker.

Dilia Ortega grew up in Huntington Park and now lives in South Gate. She works as a youth program coordinator for Communities for A Better Environment, a nonprofit that’s advocated for clean air, soil, and water in California’s working-class neighborhoods since the late 1970s.

Ortega grew up smelling rendering odors. On her way to school, she’d instinctively cover her mouth and nose when her bus drove past Vernon. Today, her role at work puts her in contact with hundreds of students in Southeast L.A. Year after year, she told LAist, they identify dead animal smells as an ongoing issue in their neighborhoods.

When AQMD was weighing whether to shut down Baker last fall, Ortega shared these insights during public comment at the three-day hearing. She underscored that she was not advocating for a permanent closure. She just wants the company to abide by the rules.

“We understand that they provide a necessary service,” she said. “But it cannot be done at the expense of our quality of life.”

Risks to public health

Jill Johnston, associate professor of Population and Public Health Sciences at USC, noted that strong odors don’t just diminish local residents’ quality of life, they can also impact their health.

Rendering plant emissions can contain chemicals like hydrogen sulfide, which smells like rotten egg, as well as chemicals that contain sulfur dioxide, she said. Some of the symptoms community members have reported — including itchy eyes and runny nose — can be caused by these chemicals. Rendering plant emissions can also exacerbate asthma symptoms, making it harder for residents to breathe, and elevate their blood pressure, Johnston said. Chronic exposure to these odor producing chemicals can also affect their cardiovascular systems.

We shared our findings regarding Baker with Johnston, including what we learned through interviews with community members and our review of AQMD’s violation records.

She said they point to “the need for more stringent enforcement of the standards, to ensure that these violations don’t persist.”

Johnston said the density of meat-related facilities in the region is also concerning and could pose a “potential cumulative burden” on nearby communities.

“Even if everyone individually is in compliance,” she explained, “when you’re exposed to so many, the health effects can be greatly amplified.”

Eleni Sazakli, a researcher at the University of Patras’ public health laboratory in Greece, specializes in studying the impact of rendering plants on local communities. She noted that odors can disrupt lives and social relationships. Even hanging laundry out to dry becomes an issue, because the wet cloth picks up the smell, she said.

Odorous chemicals produced by rendering plants can also irritate the throat and nose and “produce headaches, nausea, fatigue and sleep disturbances,” Sazakli added. Some even have the potential to cause cancer.

Pointing to the role rendering plays in reducing waste, Sazakli nevertheless maintained that rendering is “an environmentally friendly industry” that should be sustained.

“But we have to follow very strict guidelines in their operation,” she added, and “adopt the best available technologies that we have in our hands.”

What’s next for Baker’s employees

In its suit against AQMD, and on its company website, Baker warns that the shutdown could impact “about 200 people,” including “more than 100 union-represented employees.”

But when Baker asked AQMD’s hearing board for permission to resume its trap grease and wastewater treatment processes in April 2023, the company’s Jason Andreoli said no staff had been cut.

“[W]e haven’t even let go of any of our employees,” he said at the hearing. “These people are family. ”

Bertha Rodríguez, a spokesperson for United Food and Commercial Workers Local 770, confirmed that none of the 32 union members employed by Baker have lost their jobs.

Martin Perez, who works for Teamsters Local 63 and started a petition to reopen Baker, also told LAist that none of its members have been laid off. During the April hearing he said Baker had been good to its employees.

“Not only did they pay their wages, they paid their health and welfare [and] their pension contributions,” he said at the time.

The International Union of Operating Engineers Local 501, which also has union members who work at Baker, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

LAist posed the question of jobs to Goldberg, Los Angeles Unified’s school board president, and four Southeast L.A. officials who all complained to AQMD about rendering odors. All agreed that jobs are important. All maintained that the plants need to be in compliance.

“We did not want [Baker] to close, because it employed many of the people that I represent,” Goldberg said, referring to her role on the school board. “But we did want them to run their business following the regulations that they’re required to.”

“I would love to see it reopen,” she added, “but I don’t want it to reopen if they’re not going to be closely monitored and closely regulated.”

Rendering companies “need to adhere to the established regulations,” said South Gate mayor Maria del Pilar Avalos, who lives about 6 miles from Baker. When the rendering odors have been especially pungent, they’ve made her eyes burn. They’ve also caused her family members to forgo day-to-day activities, like walking their dog, she said.

Still, Avalos believes the rendering companies and local residents can coexist. “We need to see how we can utilize our 21st century technology to address those quality of life issues, so that it’s a win-win for the companies as well as for our communities,” she said.

In Vernon, plans for a moratorium on rendering plants go nowhere

In response to community concerns, Vernon’s website says the city is considering steps to strengthen local control over rendering. These include plans to enact a moratorium on building new rendering plants, along with increased fines for facilities that are not in compliance with AQMD’s odor mitigation rule.

But Angela Kimmey, deputy city administrator, said the city won’t be enacting the moratorium. The other plans are in “various stages of development,” she said. Vernon aims to encourage business growth and demonstrate that rendering plants and local residents can coexist. To this end, Vernon hosted a tour of a rendering company that’s in compliance with AQMD last summer, inviting regional and southeast L.A. elected officials to come along.

Vernon is also focused on helping facilities come into compliance, Kimmey said.

Vernon Mayor Crystal Larios added in an emailed statement that the city wants “to support our business community,” but recognizes that it has to do its part to shift toward supporting greener commerce, like data centers, green hydrogen, and the electrification of transportation.

“These types of green commerce will not only help existing businesses sustain future growth but heavily reduce the impact on air quality, minimize the number of trucks, and overall decrease the carbon footprint,” Larios said.

LAist requested an interview with Larios multiple times over a four-week period but received no response. Kimmey, who relayed the emailed statement, said the mayor was unavailable.

Hahn, the L.A. County supervisor whose district includes Vernon, told us she was disappointed to see that Baker hasn’t used available state funding to build enclosures that would contain the smells and protect community members from exposure.

Baker “doesn’t seem to think the rules should apply to them,” she said.

“We need the South Coast AQMD to be strong and hold companies accountable,” Hahn added. “I think it is important for residents in Southeast L.A. to know that, unfortunately, this fight isn’t over.”

The Jane and Ron Olson Center for Investigative Reporting helped make this project possible. Ron Olson is an honorary trustee of Southern California Public Radio. The Olsons do not have any editorial input on the stories we cover.