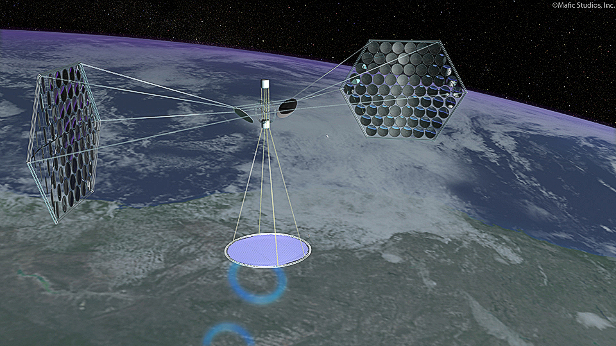

A conceptual image of what a space-based solar power plant would look like. The image was commissioned by the National Space SocietyMafic Studios, Inc.

A conceptual image of what a space-based solar power plant would look like. The image was commissioned by the National Space SocietyMafic Studios, Inc.

Space… the Final Frontier. These are the voyages of PG&E. Its five-year mission: to explore strange new technologies, to seek out new sources of renewable energy and new revenues, to boldly go where no regulated utility has gone before.

Captain Kirk’s voice keeps popping into my head as I read through utility PG&E’s 24-page application seeking regulators’ approval for the world’s first space-based solar power plant. Yep, a flying a solar farm. It’s to be built by Solaren, a stealthy Southern California startup founded by veterans of key players in the military-industrial complex — Hughes Aircraft, Boeing, Lockheed Martin and the U.S. Air Force.

By 2016 the Solaren power station is to be lofted into geosynchronous orbit and begin collecting 200 megawatts of sunlight under a 15-year contract with San Francisco-based PG&E. The solar energy will be converted into radio frequency waves and beamed to a ground station in Fresno to be transformed back into electricity and fed into PG&E’s grid. All very Dr. No.

“Solaren is using an innovative space-based solar technology, which, if successful, would represent a break-through in the renewable power industry,” Brian Cherry, PG&E’s vice present of regulatory relations, wrote to the California Public Utilities Commission on April 10.

That’s putting it mildly. The sun never sets in space and if Solaren technology works — and that’s a Star Wars-sized if — space-based solar could supply electricity 24/7 to just about anywhere in the world, including regions without access to abundant sources of renewable energy. A 2007 study by the Pentagon’s National Security Space Office found that just a one-kilometer-wide band of space in earth orbit receives enough solar energy in just one year nearly equal to “the amount of energy contained within all known recoverable conventional oil reserves on Earth today.”

No surprise that solar in space has long been a dream of scientists and military strategists but deemed technologically and economically impracticable without Manhattan Project-sized government funding and the cooperation of, well, the military-industrial complex. The technological challenge has not been so much converting solar energy into radio frequencies – that’s been done though not on Solaren’s scale – but getting a supersized solar array into space and making it work.

PG&E in recent years has transformed itself under CEO Peter Darbee from a stodgy government-regulated utility Northern Californians love to hate into one of the most environmentally progressive members of the Fortune 500. The utility has placed bets on a number of untried green technologies but it’s willingness to do a deal to put a power plant in space had some wondering if PG&E had, as Earth2Tech’s Katie Fehrenbacher put it, jumped the shark on solar, cracking under the pressure of California’s mandates to obtain 20 percent of its electricity from renewable sources by 2010 and 33 percent by 2020.

But after perusing Solaren’s patents and chatting with CEO Gary Spirnak, it doesn’t seem so sci-fi in the sky as it at sounds. Sharky, yes, insane, no.

Search online for information about space-based solar and the images that pop up are of kilometers-long structures of solar arrays connected to satellites. And therein lies a big reason space-solar hasn’t gotten off the ground — launching thousands of tons of heavy metal into orbit is exorbitantly expensive.

Solaren says it has a solution. “We want to take the weight out of these systems,” says Spirnak, talking a mile a minute. “We came up with this design concept to break these things into pieces instead of trying to construct many, many kilometers of structures in orbit, which would essentially be unbuildable.”

Instead, Solaren’s solar power station will consist of two to four components that will float free in space, kept in alignment by software controls and small booster rockets rather than heavy wires, cables and struts. “We’re moving around sunlight so we said let’s design the damn things out,” says Spirnak.

According to Solaren’s patent, an inflatable Mylar mirror a kilometer in diameter — a gigantic solar balloon, in other words — will collect and concentrate sunlight on a smaller mirror that will focus the rays on the solar array. By concentrating the sunlight on highly efficient solar cells, a smaller and thus lighter — array can be deployed.

Solaren isn’t the only company pursuing space-based solar. Space Solar boasts in impressive team of advisers, including Terry Tamminen, a former environmental adviser to California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. The company boasts an impressive Web site, but is still raising money to finance a demonstration satellite.

Meanwhile, Solaren’s Spirnak is not your typical green energy entrepreneur. He spent nearly a decade with the U.S. Air Force, running Department of Defense space shuttle flights, before joining defense contractor Hughes Aircraft. “I worked on a lot of defense projects, which I can’t talk about, satellites and things like that,” he says. (Google this guy and you’d get a blank page but for news of the PG&E deal. Solaren’s website — offline as this article went to press — offers a single page that contains no information on the company other than the slogan, “Energy for Tomorrow with Technology of Today.”)

He says he also can’t talk about who is financing Solaren, which he started in Manhattan Beach in 2001. The startup has raised several rounds of funding but acknowledges that the price tag for the 200-megawatt solar power station for PG&E will be “in the several billion dollar range” — or several times the cost of an earthbound solar farm.

“We’ve talked to investment bankers, venture people,” says Spirnak. “We’re talking to organizations that have very philanthropic and long-term views on things. These organizations are interested in green energy.”

The 2007 National Security Space Office report concluded that space-based solar posed no insurmountable technological obstacles but offers huge logistical and engineering challenges, not to mention economic ones, that would require government funding to overcome. (And lapsing into Dr. Strangelove mode, the report’s authors noted that space-based solar “has the potential to be a disruptive game changer on the battlefield … [enabling] entirely new force structures and capabilities such as ultra long?endurance airborne or terrestrial surveillance or combat systems.”)

But let’s return to earth. For PG&E, there’s little financial risk in this gambit as the utility only pays when electricity begins to fall from the sky. (What its customers will pay, though, is confidential as California puts the details of power purchase contracts in a black box. Also being kept under wraps is the utility’s own assessment of the viability of Solaren’s technology.) Whether California regulators will be willing to count a contract for such bleeding edge technology toward PG&E’s renewable energy targets is another matter.

For Solaren, it’s all about getting it right the first time. Those rocket launches are expensive and it’ll take four or five to put the power station in orbit, according to Spirnak. And if something goes wrong, you can’t exactly just pop out and fix the glitch. (“There will be a tremendous amount of redundancy built in,” Spirnak assures me.)

He says Solaren will begin launching components into space around 2012 for testing. The plan is to subcontract the actual construction of the plant to the aerospace industry.

In the meantime, the Solaren will have to navigate the brave new world of outer space power regulation. On one hand, the company won’t have to deal with the environmental issues that have dogged developers of terrestrial solar power plants — no endangered desert tortoises in space! On the other hand, the idea of beaming megawatts of radio waves through the atmosphere will doubtless raise other environmental issues – Solaren claims there’s no danger – not to mention bring out the tinfoil hat brigade.

The 200-megawatt PG&E space power station, though, is just “a pilot plant,” according to Spirnak. The real economies of scale will come from getting big – real big – which will require a new generation of big rockets.

“Our follow-on plants will be 1,000 megawatts, like a nuclear plant in space,” he says. “The more we can generate, the better our margins are.”

Below, a short video produced for the National Space Society that depicts what a space-based solar power plant might look like:

Read more:

- California’s new power source a solar farm (San Francisco Chronicle, April 14)

- Satellite may send energy to Valley (Fresno Bee, April 14)

- Startup to Beam Power from Space (MIT Technology Review, April 15)