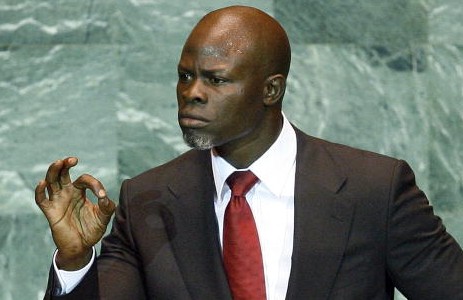

Djimon Hounsou at the U.N. Climate SummitPhoto: United NationsActor Djimon Hounsou is just as snacky in real life as he was on the big screen in Blood Diamond, The Island, and Gladiator. Better yet, he’s also a climate activist and humanitarian.

Djimon Hounsou at the U.N. Climate SummitPhoto: United NationsActor Djimon Hounsou is just as snacky in real life as he was on the big screen in Blood Diamond, The Island, and Gladiator. Better yet, he’s also a climate activist and humanitarian.

As a global ambassador for the aid and development group Oxfam, Hounsou has traveled in sub-Saharan Africa and seen the direct links between climate change and human suffering. “I’ve witnessed firsthand devastation with drought,” the Benin-born actor told reporters after he helped to kick off the U.N. Summit on Climate Change. “Year after year, [local farmers are] still expecting the rain to come pretty much as it used to. It’s not coming. So they have to adapt, with their crops and plantings.”

Not an easy proposition in a country like Mali, which Hounsou visited on a humanitarian mission. The average income in this Western African nation is about $3.29 a day.

Often the communities Hounsou travels to know that something has gone wrong, says Oxfam America President Ray Offenheiser. “We held a climate hearing in Ethiopia a week or so ago. One comment was … ‘For many many years, there were all varieties of birds here. And now the birds are gone.'”

Signs like this are signals of a “profound change” for these communities, Offenheiser says, even if “they don’t have all the information about what’s happening, why it’s happening, and what it means.”

“This is where the climate change story and the adaptation story become the human story,” he continued. “It’s about people, their lives, their livelihoods, and how they are going to change.”

One of the major points of gridlock in this year’s international climate-treaty negotiations is how the rich, industrialized nations are going to help the poorer developing nations adapt to and mitigate climate change — while also continuing to send over the aid and development dollars they already provide for a host of other reasons.

It is widely accepted now that the wealthy countries bear this responsibility; after all, they got fat and happy by creating the greenhouse-gas pollution that’s now slow-cooking the Earth. But how much help should developed nations offer? This is just one of the many contentious open questions to be addressed at December’s climate-treaty talks in Copenhagen.

Oxfam estimates that wealthy nations need to come up with around $50 billion a year to help poorer nations adapt to global warming, and about another $100 billion a year to finance low-carbon development, so that these countries can ameliorate poverty without taking a coal-and-oil-fueled path to prosperity.

Hounsou hopes that if the citizens of wealthy nations better grasp the human costs of climate change, they will pressure their leaders to ante up.

“We haven’t engaged the world population into this issue yet,” Hounsou says, noting that Western media in particular have not paid attention to the human component of global warming.

Still, “no matter how you look at it, developing nations have to initiate the discussion at Copenhagen,” he said.

Watch Hounsou at the U.N. Climate Summit: