It’s been three years since a container ship, the COSCO Busan, spilled 53,500 gallons of bunker fuel into San Francisco Bay, just after my return home to live on the bay by the sea that I love. Remnant oil still sometimes surfaces after it rains and the bay’s herring fishery has yet to recover.

It’s been three years since a container ship, the COSCO Busan, spilled 53,500 gallons of bunker fuel into San Francisco Bay, just after my return home to live on the bay by the sea that I love. Remnant oil still sometimes surfaces after it rains and the bay’s herring fishery has yet to recover.

Ten years ago, during a visit to a BP deep-drilling platform in the Gulf of Mexico, I asked the drill boss what would happen if there were a spill a mile or two down. “Guess we’ll find out when it happens,” was his response. Now we know. Every day something between four and 40 COSCO Busan spills are gushing into the Gulf from a mile below the surface.

The history of offshore drilling is the history of exploring new frontier waters with little expectation, preparation, or planning for the next disaster until it happens. After the deep waters of the Gulf, the next oil-boom frontier will be in the Arctic Ocean unless we make a serious commitment to moving, to quote a discredited oil company, “beyond petroleum.”

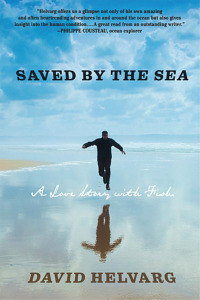

Here’s an account from the time of the COSCO Busan spill, excerpted from my new book, Saved by the Sea: A Love Story with Fish.

—–

The western grebe lies exhausted on a rock in the marina where I now live. Stained black, its red eyes seem to burn at me with anger and reproach. I know that’s anthropomorphic thinking. As humans we understand that we’re killing them, whereas they have no idea what’s killing them. The next day they boom off my neighborhood wetland to keep the oil out, although some has already gotten into the salt marsh where endangered Clapper Rails nest and where I once saw a large salmon heading up our small creek.

A spill of 53,500 gallons isn’t even large compared to dozens of historic disasters like the 8 million gallons released in and around the Gulf of Mexico after Hurricane Katrina or the 11 million gallons from the Exxon Valdez spill in 1989 that devastated the pristine waters and wildlife of Alaska’s Prince William Sound. Shortly after the COSCO Busan spill, the Black Sea and the Korean peninsula are hit by massive oil spills millions of gallons and orders of magnitude larger than this one.

Back home I walk around the marina to Shimada Friendship Park. There’s a couple, early 20s, Amber Kirst and Scott Egan. She’s walking the shoreline, her white pants oil-stained at the ankles, wearing a protective rubber glove and holding a bag full of oiled litter and dead crabs.

“We’ve got a live crab too. He was in a Cheetos bag,” she tells me, climbing up the rocks to the pathway. “We drove down from Lodi to volunteer, but they said they’d get back to us. It’s an hour-and-a-half drive. We needed to do something.”

The Cheetos crab is still alive. She shows me the small critter, with its dark shell. “Should I put it back? Is it too oiled for them to feed on?” She looks at the hundreds of shorebirds hunting in the exposed mud flats and floating just beyond. “It’s all so depressing,” she concludes before climbing back down to pick up more oiled litter.

We build our homes on barrier islands and in flood plains; we move millions of tons of goods and fuel through marine sanctuaries; we continue to burn a product that, used as directed, overheats our planet. Amber and Scott came from Lodi. They needed to do something. We all do.

Under the federal oil spill-response system established in the wake of the Exxon Valdez, a unified command has been set up including the Coast Guard, the state of California, and contractors working for the shipping company Regal Stone, owners of the Cosco Busan (“the responsible party”). If the “responsible party”‘s $61 million liability insurance ($96 million for oil rigs and tankers) is exceeded in the cleanup, then the Coast Guard will take control.

Barry McFarland, the hefty lead contractor for Regal Stone, claims that just two and a half hours after the collision, five skimming vessels were on the scene or on their way. But with just over a dozen people in the Bay Area, the contractor then had to bring in more workers from Los Angeles, Texas, and elsewhere over several days, people who were unfamiliar with the Bay and the Northern California coastline’s treacherous tides, currents, inlets, and at-risk beaches and marshes. In a better scenario, the Coast Guard, local fishermen, and volunteers could have responded in the first 24 hours, laying out protective booms and operating a flotilla of skimmer-equipped vessels in key areas before most of the oil got onto birds and beaches, but that’s not the way the system presently works. Unfortunately, the state of cleanup technology is also such that both state and federal officials consider the contractor’s recovery of 20 percent of the spilled oil a huge success.

I visit the Incident Command Center where the spill is being tracked and go out with the Coast Guard to do beach surveys around Sausalito and Richardson Bay, where I used to live. Luckily the damage here isn’t too bad, though we do run into some more oiled birds. Over 20,000 will die in the coming days.

Nine days after the spill, with 1,500 people now involved in the ongoing cleanup, I fly to Bahrain to report on the U.S. Coast Guard in Iraq for my book Rescue Warriors. I join up with 110-foot cutters protecting Iraq’s two big offshore oil terminals in the northern Persian Gulf. Along with chasing off ships that threaten to enter the security zone around the terminals, boarding Iraqi fishing dhows, and patrolling a disputed maritime line between Iraq and Iran, we do security boardings of supertankers before they fill up at the terminals.

One of the tankers, the red and green BW Noto, weighs 286,000 tons, is 1,100 feet long, and, when fully loaded, can carry 2 million barrels of oil. That’s $200 million worth of product at the time of our boarding, a hellacious amount of planet-warming carbon dioxide soon to be pumped into our atmosphere, or, if it were to spill, the equivalent of eight Exxon Valdez oil disasters.

Two weeks later, I return home to find 20 mostly Mexican contract workers in hazmat suits cleaning oil off the rocky shore behind my home. A month later, an oil barge runs into the nearby Richmond Bridge at the north end of the bay, another case of human error. Luckily no oil spills — this time.

——

But once again our luck’s run out. While I respect the roughnecks and roustabouts I’ve met on rigs off California and Louisiana (if not their corporate bosses), and also regret the lost lives and injuries they’ve suffered, I now believe that, like American whalers of the 19th century, it’s time to recognize their role in our maritime history and move on. After all, when it comes to energy production, no lives, livelihoods, coastal cultures, or marine ecosystems have ever been destroyed by a wind spill or a turning tide.