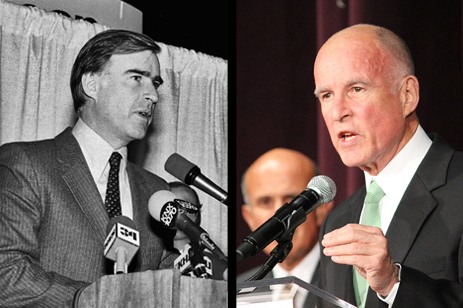

Jerry Brown, then and nowTrivia questions for energy geeks: Which state approved the country’s first energy-efficiency standards for appliances? The first green building codes? The first big wind farms? And who was governor when all those fine things happened?

Jerry Brown, then and nowTrivia questions for energy geeks: Which state approved the country’s first energy-efficiency standards for appliances? The first green building codes? The first big wind farms? And who was governor when all those fine things happened?

The answer is California under Gov. Jerry Brown — aka Governor Moonbeam — who just happens to be running for the office again, some 30 years later. Last week, Brown, the Democratic nominee, unveiled a clean-energy plan to put far more solar panels on California’s rooftops, in addition to appointing a renewable energy czar and strengthening those sexy appliance standards.

Of course, plenty of politicians make lofty promises about ushering in an energy transformation, to little or no result. Like the last eight presidents, for example. But there’s good reason to take Brown seriously.

“He’s done it before. And really if you look across the landscape in American political history, there’s nobody else that can say that,” said John Geesman, who was executive director of the California Energy Commission during part of Jerry Brown’s first stint in the governor’s mansion. “Nobody at all.”

Brown then …

When Brown took office in 1975, energy was high on everyone’s agenda. Just over a year earlier, the Arab oil embargo had driven up energy prices and triggered lines at the gas pumps. California utilities were projecting a 7 percent annual growth in electric demand, and had dreams of building a string of nuclear power plants along the coast.

Brown found another way.

In the mid-1970s, at a faculty club event at the University of California at Berkeley, he sat at the same dinner table as Art Rosenfeld, then at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, who was just beginning a noted career in energy efficiency.

They talked shop, and the conversation turned to a controversial proposed nuclear plant, Sundesert. Rosenfeld told Brown that just by requiring refrigerators to be more efficient, the state could save as much energy as would be produced by the Sundesert plant. Brown left around 9 p.m. to drive back to Sacramento. Twelve hours later, Rosenfeld got a call from Gene Varanini of the California Energy Commission.

“He said, ‘Art, I think you’d be happy to know that Jerry Brown woke me up this morning at 8 a.m. to know if this guy Art Rosenfeld is real,'” Rosenfeld recalls. “And that was the unraveling of Sundesert.”

Under Brown’s leadership, California adopted Rosenfeld’s refrigerator standard in 1978. And the state continues to lead the nation in appliance standards today, having approved the nation’s first efficiency requirement for televisions last fall. As if to underscore Brown’s achievement, several large solar projects are now planned for the old Sundesert site.

Also under Brown’s watch, California became the first state to approve a strong energy-efficiency building code, called Title 24, in 1978.

In 1982, Brown’s final full year in office, California pioneered the idea of “decoupling” electric utilities’ revenues from how much electricity they sold — which means, in a nutshell, that utilities had an incentive to promote energy efficiency rather than simply generating and selling as much power as they could. (A handful of other states have embraced electric decoupling since then.)

Brown’s California also did renewables. In the mid-1970s, the legislature passed tax credits of a whopping 55 percent for wind, solar, geothermal, and some biomass. A 1978 federal law called the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act also helped. So California started building: In the early 1980s, a wind farm at Altamont Pass, east of the Bay Area, began operating, followed shortly by two other large wind farms. The state invested heavily in solar hot-water heaters, and also put in a number of geothermal and biomass plants, according to V. John White, the executive director of the Center for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Technologies.

To be sure, Brown, who is now California’s attorney general, hardly deserves all the credit for such measures. The legislature passed important bills, such as the tax credits. Even Ronald Reagan, who was governor of California before Brown, signed the law in 1974 creating the powerful California Energy Commission, which crafts appliance standards and building codes and licenses large power plants. (According to Rosenfeld and Geesman, Reagan had vetoed a similar bill a year earlier, but then a little thing called the oil embargo came along.)

But Brown was a key advocate for these changes and he made the most of them. One of his big achievements was staffing up the California Energy Commission and turning it into an activist body, and he did the same with the California Public Utilities Commission. Together, those two regulatory entities fast-tracked many of the policy objectives set forth by the legislature, like appliance standards and building codes.

According to Rosenfeld, Brown even tried to recruit a young John Holdren, then a professor of energy and resources at Berkeley, to chair the California Energy Commission, but Holdren, who is now Obama’s science advisor, wouldn’t jump. Brown, Rosenfeld observes, has a knack “for picking future successful people.”

… and Brown now

Three decades on, California remains ahead of the country in energy efficiency. Its per-capita electricity usage has barely budged since Brown’s time despite the proliferation of gadgetry and a fondness for McMansions. California also continues to lead on solar, although without the emphasis on solar hot water that Brown had envisioned.

But on wind, the Golden State has become the Bronze State. Texas leads the nation in wind power production, having passed California for the top spot several years ago — and, embarrassingly, California now also trails Iowa, a state one-third of its size. Very few wind farms — or biomass or geothermal facilities — have been built since Brown’s time. Wind farms or other power plants can no longer be blithely sited on empty land in California — a partial legacy of the many birds that have perished at Altamont Pass.

Brown can be proud of the changes he set in motion, but in today’s California, his job will be harder. He’ll need new approaches — and he seems to get that.

His clean-energy plan [PDF] emphasizes “localized electricity generation” — read: rooftop solar — which doesn’t face siting problems. The plan calls for more than 10 times as much of this small-scale generation as California has on its rooftops now, by 2020. That’s not a cheap proposition, however.

To push through bigger projects, renewable energy advocates say Brown could help out by cutting through some of California’s notorious red tape. “I think Jerry could make a difference [in] execution and planning,” says White. “I think one of the problems in this area is there are so many agencies, so many jurisdictions, so many personalities, that things take longer than they should. They take longer than any other state.” Brown has already called for “dramatically reduced” permitting times for transmission lines.

Brown also wants to:

- build a “solar highway” of panels along state roads

- encourage energy storage systems

- set tougher efficiency standards for new buildings and appliances

- make existing buildings more efficient, in part by helping to finance efficiency upgrades for homeowners and businesses

Meg Whitman, Brown’s Republican opponent, has an energy and environment plan of her own, though it’s less detailed. She also supports further clean-energy development and promises to “work to update the law to ensure that vital infrastructure and energy projects are not stalled due to redundant reviews and overly bureaucratic processes.”

Brown, for his part, claims his clean-energy plan would create 500,000 jobs over 10 years. If he can manage that — and that’s a big “if” — he’ll live up to his campaign slogan: “Let’s get California working again.”

Do you know more about this race? Tell us in comments below. And find out about other races in our Gubernatorial Tutorial special series.