I’ve written before (more than once) that energy reformers should pay more attention to behavior. Instead there is an almost universal obsession with technology and economic cost, narrowly construed. If you think of people as rational interest maximizers, as per reigning economic folk theory, price is all that matters. You want to change behavior, you change prices. Want to change prices, make technology better. Thus the techno-obsessed American energy discussion.

No one behaves in their day-to-day life as though they or those around them are rational interest maximizers. We all recognize one another as flawed and complex, but for some reason when we talk economics or policy, we assume greedy robots. It’s baffling.

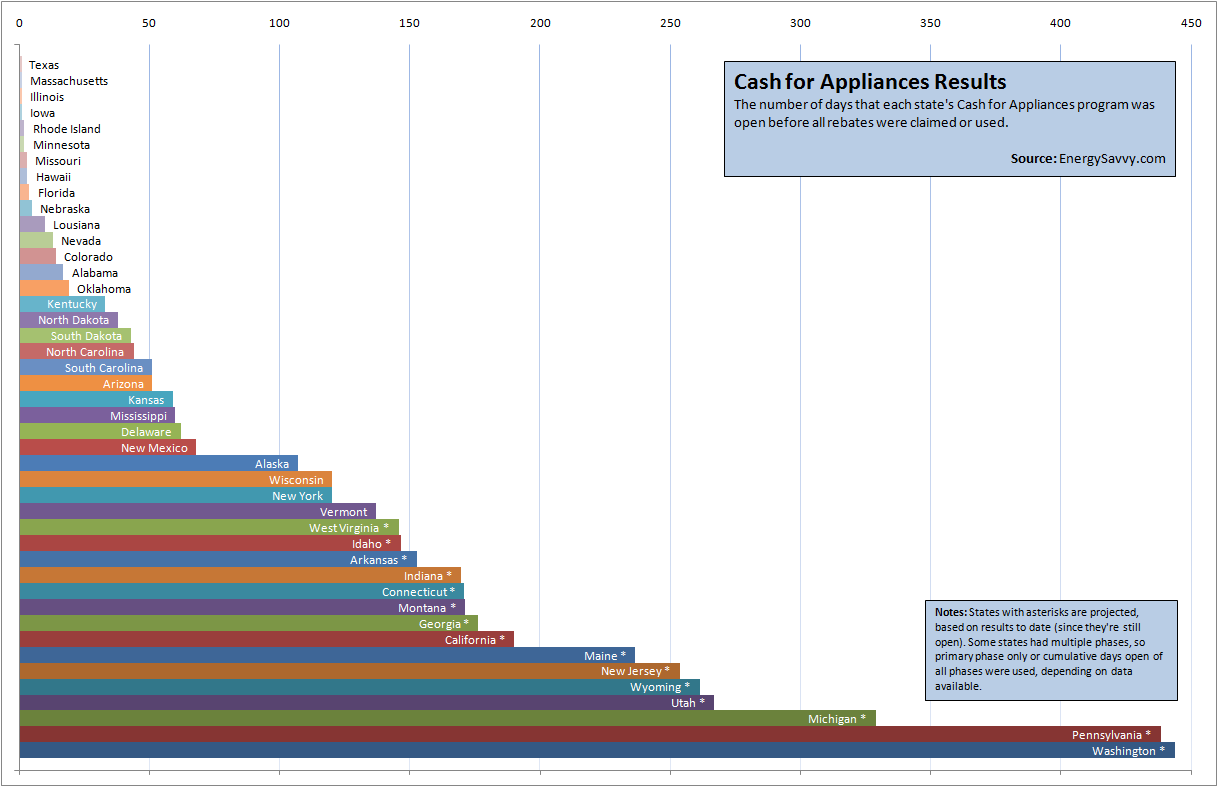

Anyway, today brings yet more evidence that Behavior Matters, from the smart folks over at Energy Savvy. Background: all 50 states have what are called “Cash for Appliances” programs, which offer rebates to people who buy energy efficient appliances. Each state had a roughly similar level of funding, around $1 per resident. Yet some states ran through their money quickly, while others took much longer, as this chart illustrates (click for larger version):

What’s up with that? Why were some state programs so much more in demand than others? Energy Savvy crunches the numbers, looking for variables that determine whether programs work. You might think the obvious answer is energy prices — maybe people who pay more for power want more rebates — but that turns out to yield almost no correlation. Nor did the size of the rebates. What predicts success?

The number one predictor of whether a state rebate program sold out quickly didn’t have anything to do with how generous the rebates were. It actually turned out to hinge on the program’s design. Virtually all the “fast” states required consumers to pre-reserve a rebate application before making a purchase. These states set up websites and call centers that “opened” at a certain date and time, creating an “event” that turned into a feeding frenzy of activity, before closing down within days, or even hours.

In his book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, Robert Cialdini lists six “weapons of influence.” Two are relevant here.

The first, commitment and consistency, has to do with …

… our nearly obsessive desire to be (and to appear) consistent with what we have already done. Once we have made a choice or taken a stand, we will encounter personal and interpersonal pressures to behave consistently with that commitment. Those pressures will cause us to respond in ways that justify our earlier decisions.

Having pre-reserved rebate applications — a formal, if non-binding, commitment — people will subsequently be much more likely to actually apply for the rebates.

The second is scarcity: the more rare something is (or is seen to be becoming), the more valuable it will appear. As Cialdini notes, “people seem to be more motivated by the thought of losing something than by the thought of gaining something of equal value.” That’s why retailers try all sorts of tricks to give the impression of scarcity, from limited-time sales to “fewer than 100 left!” electronics deals.

When rebates are offered at “events” or available only at certain prescribed times, it creates the impression of scarcity, that there are a limited number and the opportunity to get them will soon pass by. That creates a powerful incentive to act.

Two things to note:

1. The more efficacious program designs do not cost more. They advertise and distribute rebates differently, but use the same level of funding. These kinds of boosts in performance require only one thing: an understanding of human behavior. In that sense they are free, since a better understanding of human behavior can be gained for very little and shared at no cost.

2. There are four more weapons of influence (reciprocity, social proof, authority, and liking) that could be deployed to drive even faster adoption of clean energy and efficiency. Properly brought to bear, they can achieve further low- or no-cost performance improvements in energy programs. All that’s necessary is for policymakers and analysts to learn the rudiments of social psychology; it needs to become part of the policy vocabulary, just like technology and economics.