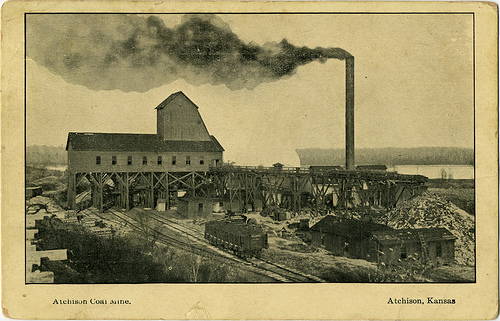

Bring in the chimney sweep!Photo: Thiophene GuyDearest readers,

Bring in the chimney sweep!Photo: Thiophene GuyDearest readers,

In our last book club conversation about Bill Bryson’s At Home: A Short History of Private Life, we discussed some of the sordid history of the food we eat. Now let’s turn our attention to the way we heat.

Back in the Middle Ages, people were in desperate need of heat sources. In those days, houses were typically warmed in winter via an “open hearth” in the middle of the house’s main and only room. Bryson compares it to “having a permanent bonfire in the middle of the living room.” Chimneys were unknown.

Bryson writes, “What you did was you had an open fire, and all the smoke just kind of leaked out a hole in the roof. A fire in the middle of the room radiates heat much better than a fireplace does, but it also meant that there was a lot of smoke and sparks and things drifting about.” At any given moment, smoke might waft into the face of anyone inside the home. The average abode was permeated by a constant campfire smell.

When the chimney was finally introduced in the 14th century, it permanently revolutionized the Western house, and the more efficient ventilation system meant a revolution in what could be burned.

Bryson writes: “Chimneys also permitted a change in fuel to coal — which was timely because Britain’s wood supplies were rapidly dwindling. Because coal smoke was acrid and poisonous, it needed to be contained within a fireplace.”

As Bryson notes, there were unintended consequences to the new system: “This made for a cleaner house but a filthier world outside.” People pined for the old times, when wood smoke hit them in the face instead of coal soot. “As late as 1577, a William Harrison insisted that in the days of open fires ‘our heads never did ake.'”

This headache was just a hint of all the pain that burning coal would bring to the planet in the generations and centuries to come. But people needed power. So power from coal went to the people. The chimney was like the first “clean coal scrubber,” of sorts.

Homes were not only hard to keep warm — until the last 150 years or so, they were also extremely hard to keep lit. In his chapter “Fuse Box,” Bryson attempts to convey what the pre-industrial world actually looked like once the sun went down:

We forget just how painfully dim the world was before electricity. A candle, a good candle, provides barely a hundredth of the illumination of a single 100-watt lightbulb. Open your refrigerator door, and you summon forth more light than the total amount enjoyed by most households in the 18th century. The world at night, for much of history, was a very dark place indeed.

In an interview on The Colbert Report, Bryson says, “We’ve spent huge amounts of energy since the Industrial Revolution. Of all the energy that’s been produced since the Industrial Revolution began, half of it has been consumed in just the last 20 years.”

Do you think knowing about the past helps us better plan the future? What did you think of the book overall? Please share your thoughts in the comments.

If you have any suggestions for our next big read, feel free to add those to the comments below too. We’ll announce the book for March next week.

Warmly,

Umbra