On a recent spring evening in Seattle, a crowd of nearly 1,000 gathered for a glimpse at one of the Democratic Party’s rising stars. When Washington Governor Jay Inslee bounded on stage, the audience let out a gasp, and collectively rose to its feet to offer a standing ovation.

Inslee was actually there to introduce Stacey Abrams, the Georgia Democrat who narrowly missed becoming the first black woman to be elected governor of a state. “I speak on behalf of 7 million Washingtonians in welcoming Stacey Abrams to the great state of Washington,” Inslee proclaimed, inviting his colleague from the South to join him at the lectern.

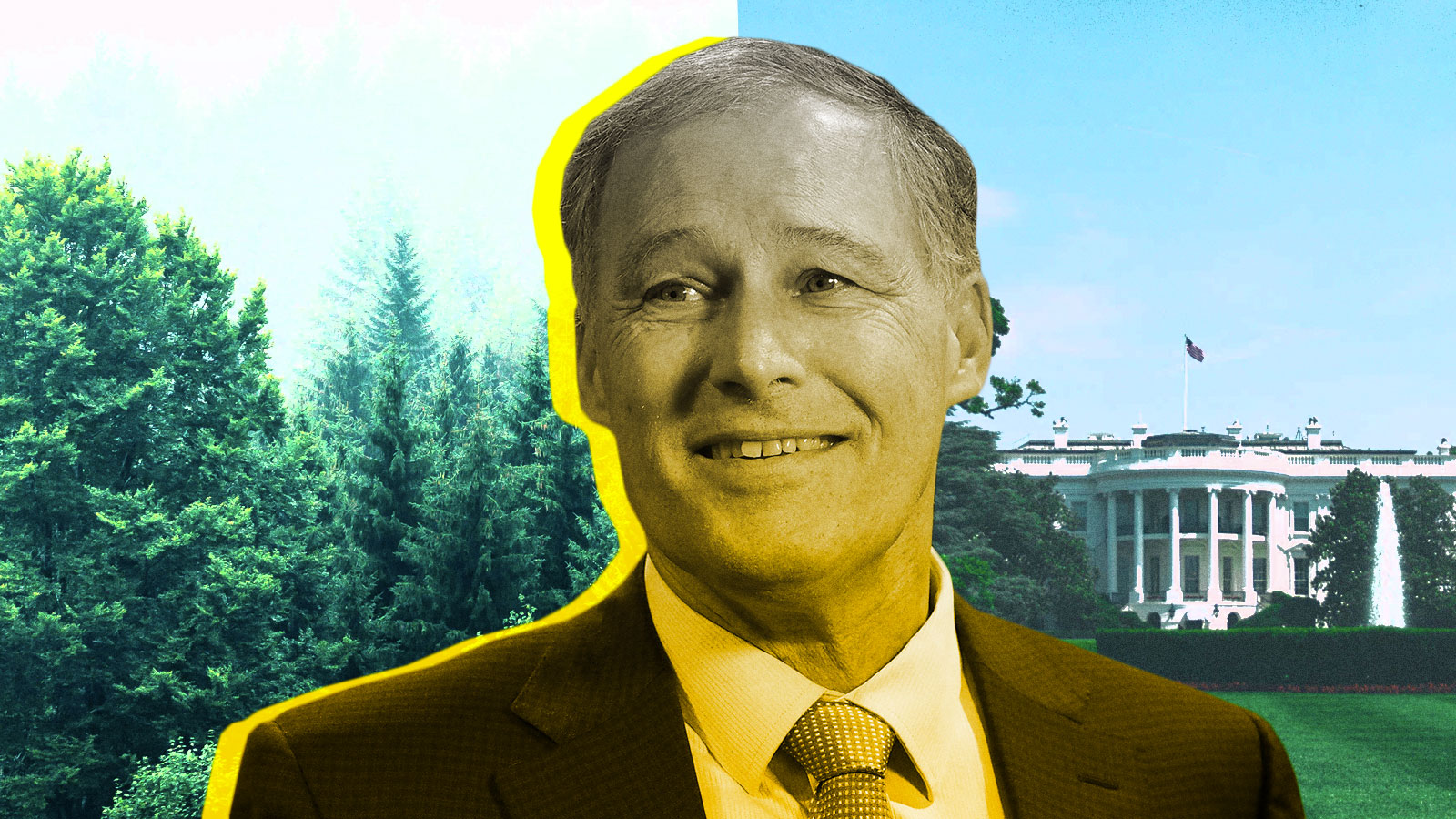

Like Abrams, Inslee hopes his star is on the rise. It’s been more than two months since he jumped into a then-crowded, now-overflowing Democratic presidential primary with one major item on his agenda: climate change.

In some respects, Inslee’s decision to run as the climate candidate couldn’t come at a more opportune time. Recent polling shows warming is the No. 1 issue for Democratic voters. And Inslee is in the midst of signing a slew of bills into law that will make Washington a national leader on climate.

Outside of his home state, however, crowds would likely be less moved to standing Os if Inslee unexpectedly appeared in front of them. He is currently polling at 1 percent. When I brought that fact to his attention, he quipped, “Solid!” But that level of support is barely enough to qualify for the dozen primary debates that will commence this summer.

More importantly, though, candidates with higher name-recognition are beginning to encroach on the ground he’s staked out. In 2016, it would have been easy for Inslee to set himself apart as a climate champion — presidential candidates spent a total of 5 minutes and 27 seconds discussing the issue. In 2019, the topic is a top-tier primary issue.

Already, Senators Elizabeth Warren and Cory Booker have released climate-related policy proposals focusing on public lands and environmental justice, respectively. This week, former Texas Representative Beto O’Rourke unveiled what was at the time the most comprehensive climate change plan of the bunch, aiming for net-zero emissions by 2050.

On Friday, Inslee came out with his own “100% Clean Energy for America Plan,” the first plank of a wider platform called the “Climate Mission.” It includes many of the positions that are gaining consensus among 2020 hopefuls: no drilling on public lands, re-enter the Paris climate agreement, ban highly polluting hydrofluorocarbons, and end tax breaks for fossil fuel companies, among other policies.

Where Inslee stakes out some new territory is with the three-pronged, central portion of his plan: Within a decade, he wants to eliminate pollution from new cars, new buildings, and our energy grid. Under the broader Climate Mission, he aims to get America to net-zero pollution by 2045 — five years sooner than Beto’s plan.

It’s an ambitious timeline, but by the time the debates roll around, Inslee expects to have a list of accomplishments in Washington that he can point to as evidence that his agenda could scale nationally. “Talk doesn’t cut it,” he told Grist. “You have to be able to actually do things, and frankly, I’m the only candidate in this race who has actually achieved results.”

Three climate-related measures proposed in Washington state — two of which Inslee will sign into law next week — appear to serve as mini-models for what he could push for if he landed in the White House.

Building efficiency

One of the bills the governor expects to sign soon will require new buildings in Washington to adhere to efficiency standards. The bill directs the state to develop efficiency standards that will ratchet down energy use over the next decade. The bill also includes incentives for existing buildings to be retrofitted to comply with the new standards. San Francisco and New York are in the midst of passing similar requirements, but Inslee says his is the first to include the retrofit component.

His presidential climate plan works much the same way. In it, he advocates for a national Zero-Carbon Building Standard by 2023 for new commercial and residential buildings, and notes that future proposals will include a plan to retrofit existing buildings. “It is a big deal because it is not romantic,” Inslee said, referring to building efficiency. “It’s the single most cost-effective, money-in-the-bank job creator of all the things we do.”

100-percent clean energy

Inslee also expects to sign a 100-percent clean electricity bill into law next week. It would eliminate use of coal power in his state by 2025 and require utilities to achieve 100 percent clean electricity generation by 2045. The law will also incorporate some of the environmental justice elements that Green New Deal advocates are championing. For instance, his bill would require that utilities take into consideration the social cost of carbon — the environmental and social damage inflicted per ton of emitted carbon. That’s another first nationwide, by the way. “It makes utilities potentially work on a performance-based system,” Inslee said, which means utilities will have incentives beyond profits for shareholders. “That’s a fundamental change.”

The national version of that bill looks similar on a slightly different timeline: It calls for retiring the U.S. coal fleet by 2030, and 100 percent carbon-neutral power by the same year (100 percent renewable electricity by 2035). And it includes a comparable switch to a performance-based system for the nation’s utilities, as well as measures that safeguard front-line communities against price hikes and pollution.

Clean vehicles

There are currently fewer than 43,000 electric cars on the road in Washington, but Inslee believes the state is still on track to meet his target of having 50,000 electric vehicles on its streets by 2020. The governor helped set up an electric vehicle charging system along his state’s highway system in 2018. He also pushed for a clean fuel standard that would have resulted in the emissions reductions equivalent to taking one-in-five cars off the road, but when that failed in the legislature, he changed course and tried to pass a state-wide cap on carbon emissions by executive action instead. It’s currently tied up in the state’s Supreme Court. “That would be the cherry on top if we got that,” he said.

His presidential plan is a bigger lift. It aims for zero emissions from new passenger cars, medium-duty trucks, and buses by 2030. That means that 100 percent of new lightweight and medium-duty cars sold in America would have to be zero emission within roughly 10 years. Inslee also aims to take a version of his low carbon fuel standard — the one that failed in his state — and apply it on a federal level. The same goes for a new nationwide EV charging system.

While Inslee’s on a bit of a roll of late, he hasn’t always had success with his climate initiatives. The governor presided over multiple carbon tax initiatives that failed both in the Washington legislature and at the voting booth. In a recent poll conducted by the New York Times, Inslee indicated he was undecided about implementing a carbon tax should he become president.

“If one thing is not working, you go to plan B, and that’s what we’ve done,” he told Grist. He added that if all of the recent climate bills he’s been championing manage to pass, it’ll have roughly the same CO2 savings as a carbon tax would have anyway.

While the legislation being passed in Olympia burnishes Inslee’s bona fides, working against him on the national stage is the prominence of the Green New Deal. Being pushed by the progressive wing of the Democratic Party, it’s quickly become a reference point for the climate conversation on the left. Many of Inslee’s fellow 2020 hopefuls have lined up behind the ambitious resolution — even though there’s no concrete policy tied to it yet.

When O’Rourke unveiled his surprisingly bold climate plan earlier this week, spokespeople for the Sunrise Movement, one of the main groups championing the Green New Deal, attacked his proposal. They criticized it as not aggressive enough and said that “the United States should do much more.” They argued that the 2050 goal post was insufficient and that the U.S. should shoot for net-zero domestic emissions by 2030 instead, a target widely considered impossible. (They’ve since walked back their criticism, calling O’Rourke’s plan “a great start.”) Compared to Beto’s plan, Inslee’s proposal is only five years closer to what Green New Dealers are demanding.

The question remains as to whether the Green New Deal will survive the primary season as the gold standard for climate action among Democrats, or if stances will soften heading into the general election. Back in 2007, Inslee co-authored a book called Apollo’s Fire: Igniting America’s Clean Energy Economy, which outlined a climate action plan very similar to the Green New Deal.

When I pressed him for a position on the proposal championed by progressive rock star Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and others, the normally folksy Inslee seemed irritated. He’d heard this question many times before. “I support the Green New Deal, is that what you’d like to hear?” he asked, lifting his palms toward the ceiling in a hopeless gesture. “I support the Green New Deal.”

Honestly, it’d be hard for him not to back ambitious climate goals, given the sole focus of his platform. But if the climate candidate wants his star to rise above a crowded field, he has to hope that his longtime clean-energy evangelism and the most ambitious plan to tackle warming (so far) carries more weight than just being another hopeful willing to embrace the Green New Deal.