How do we feed the world’s growing population without wrecking the earth? It’s a question that looks especially urgent given estimates that some 9.8 billion people will inhabit the planet by 2050, up from 7.6 billion now. Without improving techniques and technology, feeding all of them would require putting an area twice the size of India under plow and pasture while emitting as much carbon as 13,000 coal plants running nonstop for a year, according to a report published on Wednesday by the World Resources Institute.

The Washington D.C.-based think tank has been working on this report for the last six years, looking for a solution to our existential triple challenge: feed everyone and shrink agricultural emissions to keep the world from heating more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, all without clearing more land for farming. The WRI’s report lays out a way that everyone could get enough to eat in 2050, even as we turn farmland into forest and allow carbon-sucking trees to spread their leaves over an area larger than Australia.

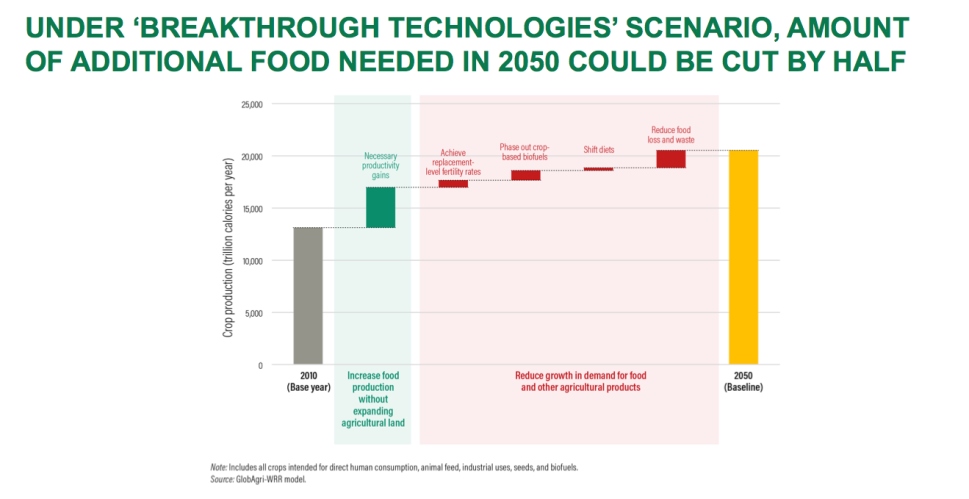

The report recommends an all-of-the-above approach starting with reducing the size of harvests needed. By eating less meat, leveling off population growth, reducing waste, and phasing out biofuels, we could reduce the amount of additional food needed by half:

World Resources Institute

But diminishing demand for meat by getting more people to go vegan just isn’t enough.

“There’s a tendency in this field for people to treat dietary change as a magic asterisk where somehow we wave our hands and there will be an overwhelming reduction in meat eating,” said Tim Searchinger the Princeton professor who led the research on this report. “We wanted to focus on things that were realistic and achievable.”

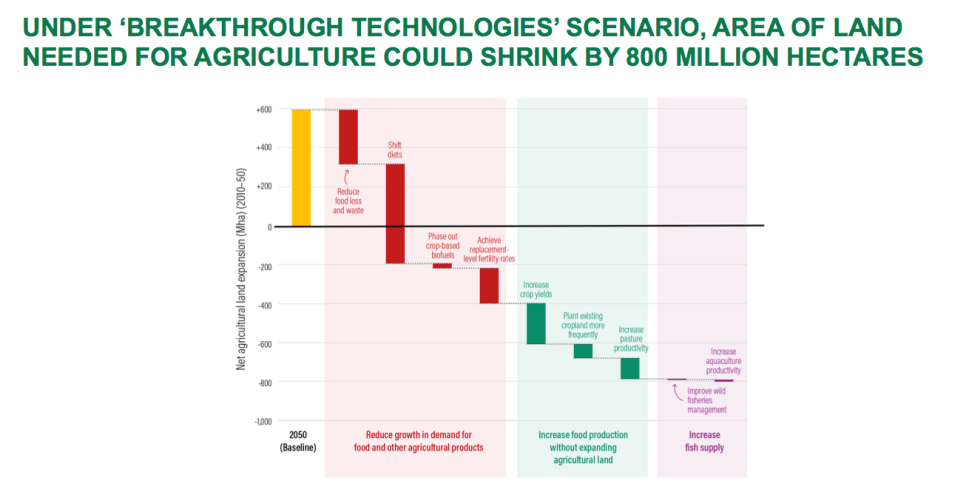

If we also develop better seeds and animal breeds and use existing farm and pasture-land more intensively, we could shrink our agricultural footprint by 800 million hectares, an area bigger than Texas.

That’s important, because the world needs to cover at least one Texas with trees to keep temperatures below 1.5 degrees of warming. And, as the chart below shows, we’d have to do all of the above and more if we want to make agriculture do its part in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Pulling all this off seems daunting, but the researchers divided the action needed into a 22-item “menu” with discrete recommendations like eating less beef and lamb, and breeding crops that can withstand higher temperatures.

“Not everything on the menu is going to be for everyone,” said Richard Waite, a WRI researcher who worked on the study. “But there’s something for everyone whether you are just shopping for your family, or in charge of food procurement for a major company,”

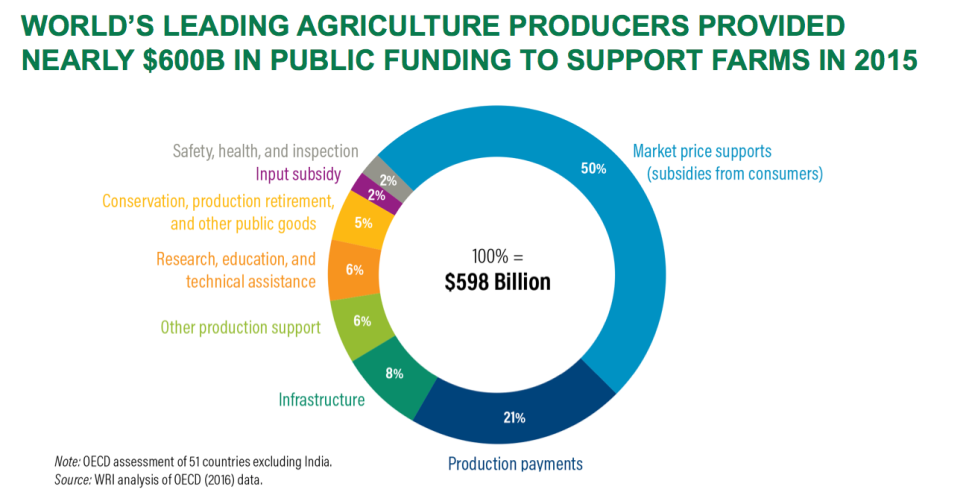

The report also points out that very little of the $600 billion a year governments spend on agriculture goes toward the innovations that would give us a sustainable food system. Agricultural research and development gets just $50 billion a year — that’s including private funding and public support.

World Resources Institute

Most of the money for agriculture comes in the form of subsidies and price-supports that shelter farmers from changes in the industry. The report says if those funds were diverted to programs that reduce food waste, squeeze more food from the ground, and study how to improve soil health, the world could solve this three-headed monster of a problem.