Environmentalists have cheered “valve turners” who illegally cut off oil and gas flows through pipelines. Now their political allies are turning off valves on gas pipelines that connect to buildings in their own towns.

Berkeley, California just became the first city in the country to ban gas pipelines — the little ones that go into houses. The city council voted unanimously on Tuesday to prevent any new buildings from hooking up to natural gas starting next year. That means thousands of new housing units planned for construction over the next few years will have water heaters, furnaces, and stoves that run on electricity instead of natural gas.

Like many progressive cities on the West Coast, Berkeley has a history of passing bans on evils — like straws and bags — and reading the progressive mood. At the same meeting, for instance, the city resolved to start using the term “maintenance hole” in place of “manhole.” But if other cities follow suit on this particular ban, it could lead to a significant shift in the way the United States uses energy.

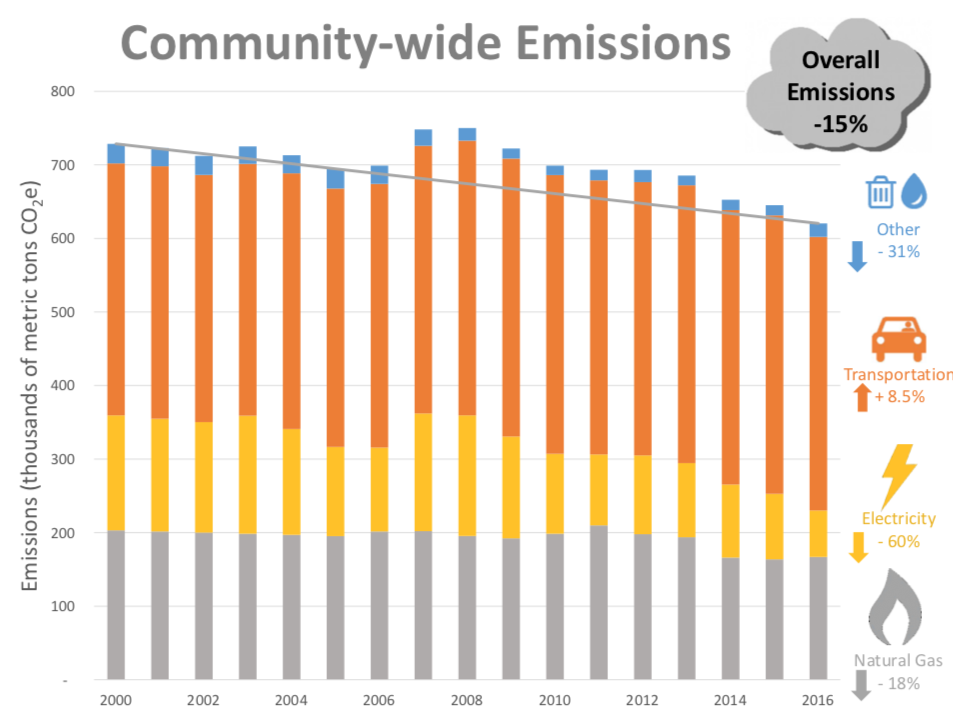

Berkeley is doing this because it has pledged to eliminate all its greenhouse gas pollution by 2030. And it’s already had some success: The city’s emissions have dropped 15 percent since 2000, mostly by cutting electricity use.

Falling, but not fast enough to meet goals. City of Berkeley

Natural gas is an obvious target: Its use in homes and offices accounts for 27 percent of the city’s greenhouse gas emissions. But it’s hard to switch houses and buildings off fossil fuels in a hurry because appliances like furnaces last a long time. If you install a brand new gas-burning heater today, you probably aren’t going to think about replacing it for 15 years or so. So it makes sense to start by requiring developers to install appliances that don’t burn fossil fuels.

But getting rid of gas only makes sense if the electricity that replaces it produces less pollution.

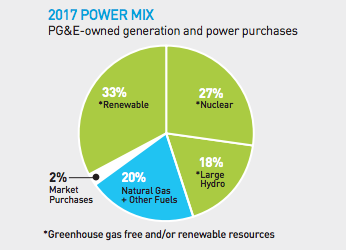

Northern California’s power mix is mostly clean. PG&E

Berkeley gets its watts from East Bay Community Energy, which buys at least 85 percent of its electricity from carbon-free sources. Heating houses with electricity may be a challenge, however, as California becomes more reliant on solar energy, because people like to turn on the heat on long winter nights when solar power is absent. As it happens, Northern California gets 27 percent of its electricity from nuclear power, another carbon-free source, but that’s slated to shut down by 2025.

Most residential natural gas burns in water heaters and furnaces. But the 7 percent of the gas that goes to stoves tends to dominate the conversation. Berkeley’s foodies might be miffed. Many prefer gas stoves to electric, arguing that the burners are easier to control, heating up and cooling down faster. But the truth is that electric ranges have gotten pretty slick in recent years.