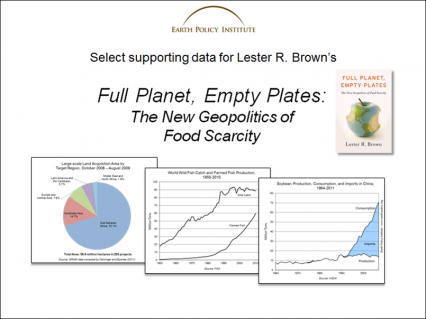

More than 150 data sets accompany Lester R. Brown’s latest book, Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity. These tables and graphs help to explain the precarious situation in which humanity finds itself, as the world leaves an era of food surpluses and enters one of food scarcity. Here are some highlights from the collection.

Food Prices Rising

Between 2007 and mid-2008, world grain and soybean prices more than doubled. Record food price inflation led to food-related riots and unrest in some 60 countries. Prices eased somewhat due to the Great Recession, but even then remained well above historical levels. In late 2010 into early 2011, prices spiked again to a new record high, helping fuel the Arab Spring. As farmers struggle to keep up with soaring demand for grain and soybeans, this ratcheting upward of food prices ensures that many of the 219,000 new guests at the global dinner table each night are facing empty plates.

In decades past, when food prices spiked, the world could return idled U.S. cropland back into production or draw down grain stocks. But now these two safety cushions are gone: the U.S. cropland set-asides have been phased out, and over the last decade world grain reserves have averaged a dangerously low 74 days of consumption.

The world’s farmers are now essentially in a situation where a record grain harvest is needed each year just to keep up with the rise in demand. Close to 80 million people are added to the world population each year. Meanwhile, some 3 billion people with rising incomes are looking to “move up the food chain” and consume more grain-intensive livestock and poultry products. Additionally, some countries, especially the United States, recently have begun turning massive amounts of grain into fuel for cars—feeding cars instead of people. In the United States, the world’s leading corn producer and exporter, more corn is now sent to ethanol distilleries than is used in livestock and poultry feed.

Unfortunately several negative trends are also converging on the supply side of the food equation. These include water tables falling as a result of overpumping for irrigation, the loss of fertile topsoil due to overplowing, and weather patterns becoming less predictable as the planet warms. Recent heat waves and droughts, such as in Russia in 2010 and in the United States in 2012, give the world a preview of how climate change can devastate crops.

Another limit on future grain production is emerging as some of the more agriculturally advanced countries appear to have hit a “glass ceiling” for grain yields. For example, Western Europe’s three leading wheat producers—France, Germany, and the United Kingdom—have not increased wheat yields for over a decade. Japan’s rice yields plateaued in the late 1990s at just below 5 tons per hectare. In China, the world’s number one rice producer, rice yields are now approaching those in Japan and may not be able to surpass them.

The Global Land Rush

When grain prices took off in 2007-08, some grain exporters such as Russia and Viet Nam restricted or even banned exports in hopes of keeping their domestic food prices from spiraling out of control. A number of grain importing countries, no longer confident that they could rely on the international market, attempted to buy or lease large tracts of land abroad on which to grow food for themselves. Led by investors from countries like South Korea, Saudi Arabia, and India, the bulk of land acquisition has occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. Ethiopia and the Sudans, where millions depend on international food aid, are principal targets.

The global land rush is not limited to investors seeking to farm abroad for food security. Others are interested in producing biofuels to meet U.S. or European Union renewable fuel goals, or in producing industrial crops such as timber, rubber, or sugar. Land is also seen as a lucrative investment opportunity by university endowments, investment banks, and pension funds.

Preventing a Food Breakdown

The world can overcome the challenges facing agriculture, but not with business-as-usual approaches to food, population, and energy. It will take something like a wartime mobilization to meet four key goals: stabilize climate, restore the earth’s natural support systems, stabilize population, and eradicate poverty. The good news is that in many ways these goals reinforce one another. For example, the shift to smaller families helps bring people out of poverty, and vice-versa. The education of all children, boys and girls alike, is needed to eradicate poverty and stabilize population, and ultimately will play a role in helping the world achieve lasting food security.

Scroll through some of the key graphs in the slideshow on our website or on the EPI SlideShare page. Additional figures and tables are posted along with the first chapter of Full Planet, Empty Plates on the Earth Policy Institute website, www.earth-policy.org.