The Glasgow climate pact, the final agreement that came out of this month’s United Nations climate summit, is filled with fuzzy statements. It “urges,” “requests,” “invites,” or “welcomes” nations to do things, like increase their financial support to developing countries, or revise their climate plans to aim for steeper emissions cuts. With nothing actually required of countries after this momentous round of international negotiations, it would be easy to assume that the agreement accomplished little.

However, one portion of the deal will have a very concrete outcome. After years of tense debate, world leaders committed to rules for a new international carbon market. Now, countries will be allowed to fund projects that reduce emissions in other countries, like solar farms or reforestation, and count the climate benefits toward their own national greenhouse gas goals. But it’s a scheme where the risks are as high as, if not higher than, the rewards.

Proponents of this new U.N.-regulated carbon offset market see it as a way to goad wealthier countries into doing more to cut emissions by making it cheaper to do so. The idea is that for some countries, paying for climate-beneficial projects in other parts of the world might be more cost-effective than doing it at home.

Kelley Kizzier, who has worked on international carbon market negotiations for more than a decade and is now the vice president for global climate at the Environmental Defense Fund, is one of them. In addition to making climate action cheaper, she said the carbon market is an important tool to get more finance flowing into developing countries to help them grow sustainably. Private companies will now have an incentive to build green projects in poorer countries because they’ll be able to finance the projects by selling carbon credits on the newly created international market.

Kizzier applauded the deal in Glasgow. “Today’s agreement on Article 6 provides the rules necessary for a robust, transparent, and accountable carbon market,” she said in a statement after the decision was finalized.

Accounting problems

The market was initially devised in 2015 in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, but it has been in limbo ever since as climate negotiators have tried to reach a consensus on how to implement it. The stakes were high — with poorly-written rules, the whole scheme could cause global emissions to go up instead of down. A common refrain at international meetings was “no deal is better than a bad deal.” More than anything, the debate centered around issues of accounting. What if both the country that funded the solar farm and the country that hosted it deducted the carbon emissions prevented by that project from their greenhouse gas balance? It might create the appearance that the world was making more progress than it actually was.

That issue of double counting was finally settled in Glasgow, and some experts said the new rules are strong. “I think the primary way in which this could have been bad is the double counting issue,” said Derik Broekhoff, senior scientist at the Stockholm Environment Institute, a nonprofit think tank. “I think that was resolved in a way that’s pretty solid.”

It was resolved in a way that may sound obvious. The rules say that if a country hosts an emissions-reduction project and transfers the emissions savings to another country, it must report the transfer to a U.N. supervisory board and adjust its own greenhouse gas accounting accordingly. Some countries wanted to make these adjustments for certain transfers, but not others, but in the end, all transfers are subject to this rule.

Part of the reason it’s complicated is that countries have different kinds of official climate goals under the Paris Agreement. Some have economy-wide greenhouse gas reduction targets, while others only aim to reduce emissions in certain sectors. Still others don’t have emissions targets at all, but rather a goal to produce a certain amount of renewable energy or to conserve a certain amount of their forests. Broekhoff said that the new agreement makes it clear that countries need to translate their goals into emissions metrics before they can engage in international trading.

A history of human rights abuses

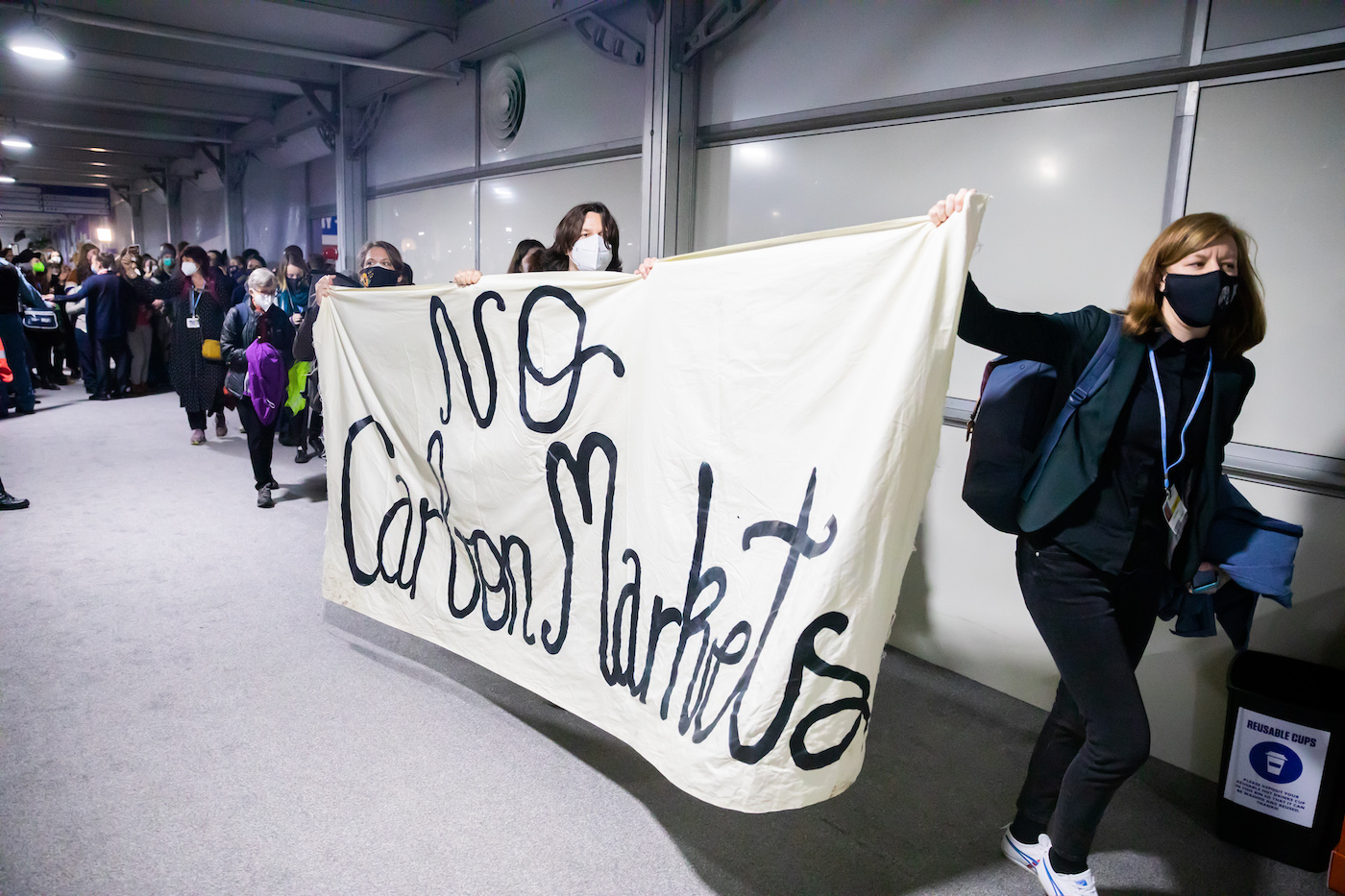

The potential for double counting of emissions reductions is not the only risk of the new scheme, which is why many climate experts and activists are sour on the idea of carbon trading. Indigenous communities, in particular, are wary of what the new market will mean for them due to a history of abuse against their lands and rights as a result of carbon trading.

“Article 6 still places our lands at risk,” said Kailea Frederick, a climate justice organizer at NDN Collective, an Indigenous-led advocacy organization. “Like other extractive industries and economies, carbon trading contributes to continued land dispossession from Indigenous communities, and in this land theft, violations to our human rights.”

This is the second time the U.N. has tried to implement an international carbon market, and the first time was something of a horror show for many Indigenous communities. The earlier program was called the Clean Development Mechanism, or CDM, and it was developed under the Kyoto Protocol, the 1992 climate pact that was supplanted by the Paris Agreement. At the time, only developed countries had official emissions targets, so there was no risk of double counting. But CDM projects racked up a destructive track record. Hydroelectric dams built in Chile, Panama, and Guatemala flooded Indigenous lands and displaced communities. Villagers in Uganda were forcibly expelled from their homes and lands and threatened with violence to make way for a tree plantation.

Frederick said that Indigenous peoples and human rights advocates have been pushing for new safeguards to be baked into the carbon market rules during the last six years of international climate meetings. They demanded an explicit reference to the need to obtain the free, prior, and informed consent from Indigenous communities before implementing projects, and a way to report grievances when abuses occur. In the Glasgow pact, the grievance mechanism was included, as well as instructions to “respect, promote and consider” human rights and the rights of indigenous people. But the International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Climate Change, a caucus for Indigenous communities at the United Nations climate talks, called the language on consultation “totally inadequate.”

To Frederick, even if the safeguards were stronger, the carbon market is a step in the wrong direction. “Carbon trading is not a conversation on what needs to change in our consumption model, but instead allows governments, extractive industries, and big polluters to continue with business as usual,” she said.

‘Paper reductions’

That sentiment is common among skeptics of carbon offsets. Today, there is some government-regulated carbon trading in the European Union, China, and California, where big polluters buy carbon credits that enable them to comply with local laws while continuing to emit. There is also a vast unregulated market where companies and individuals voluntarily purchase carbon credits because it makes them appear more green. Typically, one carbon credit is meant to be the equivalent of one metric ton of carbon that has been prevented from going into the atmosphere — for example, by building a solar farm that reduces coal power generation — or that has been actively removed from the atmosphere, possibly by planting some trees.

Past investigations into carbon offset projects have found that many of them overestimate how much they reduce emissions, or worse, have no climate benefit at all. The CDM suffered from the same deficiencies, with research showing that many of the projects would have happened even if rich countries hadn’t subsidized them. A study conducted for the European Union found that 73 percent of CDM credits generated between 2013 and 2020 were unlikely to be “providing real, measurable and additional emission reductions.”

It will be up to the overseers of the new carbon trading scheme at the U.N. to develop stronger standards that ensure that the system truly does reduce emissions. But unfortunately, the deal made at COP26 allows millions of carbon credits that have been generated for the CDM since 2013 to be sold on the new market. Not only are many of those credits suspect, but this means that countries will be able to offset their emissions by paying into projects that were developed almost a decade ago.

“Those are paper reductions at this point,” said Broekhoff, who hopes that countries will opt not to purchase those credits. “I’m cautiously optimistic it will be somewhat toxic to use those.”

Signs of progress

Despite the weak language on Indigenous and human rights and the flood of CDM credits, the Glasgow agreement contained some details that pleased even carbon market critics, like the folks at the nonprofit watchdog organization Carbon Market Watch. For example, the rules require that a share of the proceeds from carbon trading go into the United Nations Adaptation Fund, which is disbursed to help poorer nations shore up their infrastructure against rising seas or create early warning systems for storms. The lack of finance for such projects in developing nations, which have done little to contribute to climate change but must deal with its consequences, was a major point of contention in Glasgow.

The new rules also ensure that carbon exchanges serve to lower overall emissions, rather than just allowing one country to offset its emissions with reductions somewhere else in a zero-sum game. Two percent of the credits in every transaction will be canceled — not able to be claimed by any country.

“Two percent is low, but it’s super important that that was included as mandatory,” said Jonathan Crook, policy officer at Carbon Market Watch, who said the percentage could be increased in the future. “Countries are basically saying that the typical offsetting mentality isn’t adequate. This two percent of credits are basically never counted by anyone, and they only benefit the atmosphere.”

Crook said the carbon market does have potential to advance climate action and distribute sustainable development funds to places that sorely need it. But he stressed that countries should not be substituting the hard work they need to do within their borders to reduce emissions with carbon offsets. And he’s concerned that offset projects will focus on helping developing nations implement projects that they could easily implement themselves. “We need to be targeting high-hanging fruit that are difficult for a country to attain. If it ends up targeting all the low-hanging fruit, then the country is left with all the difficult work to do,” he said.

Broekhoff said he’s just glad that negotiators at COP26 finally reached an agreement, because there’s symbolic value in having this foundation in place for international cooperation. “The perception of negotiators getting together and failing to agree on these rules I think would have been kind of a vote of no confidence,” he said. “At this point, it’s up to countries to now use this tool responsibly.”