A Swiss company on Wednesday is set to become the world’s first to commercially remove carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere and turn it into a useful product.

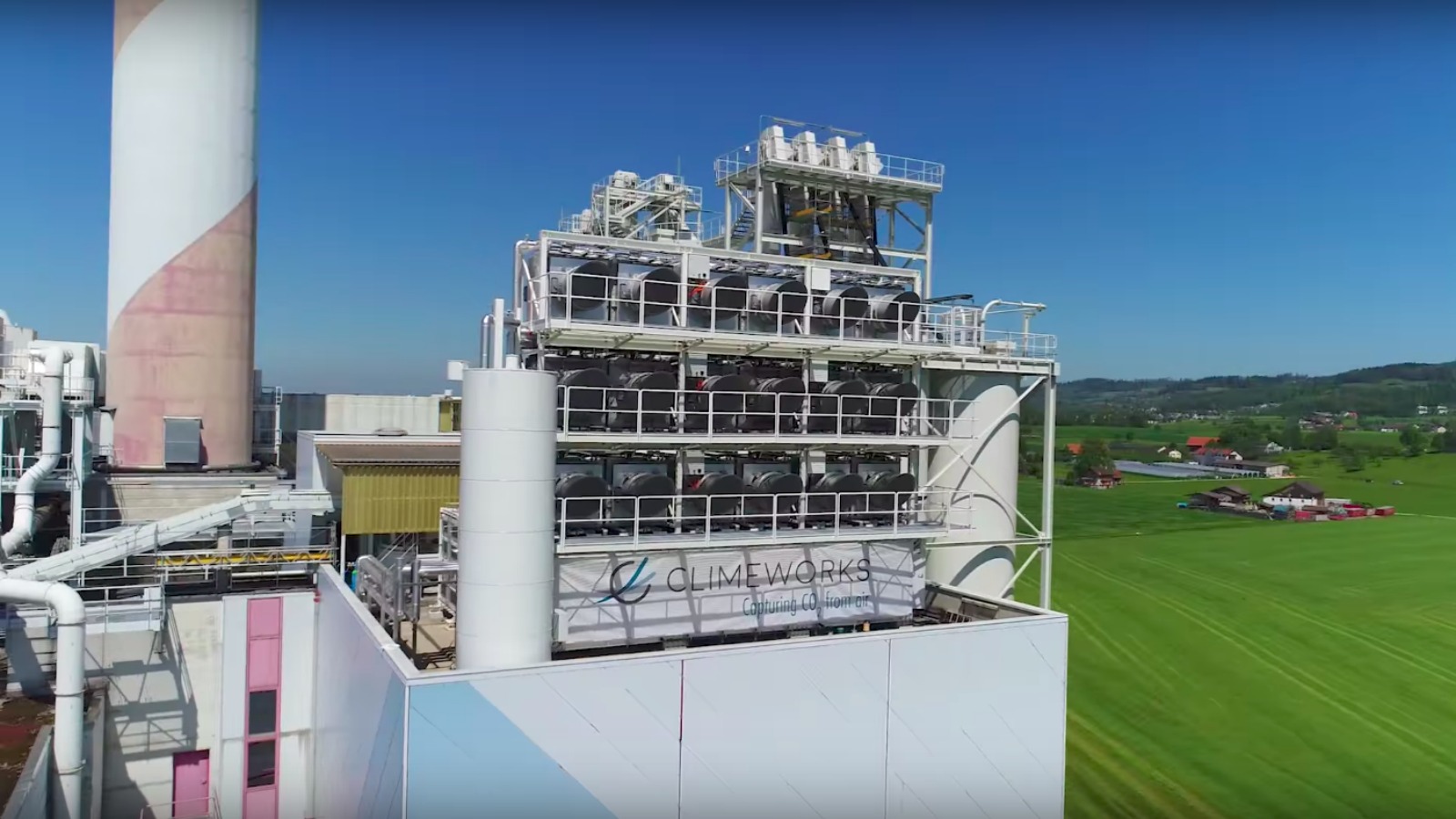

Climeworks, which will begin operations at a facility near Zurich, Switzerland, plans to compress the CO2 it captures and use it as fertilizer to grow crops in greenhouses. The company wants to dramatically scale its technology over the next decade, and its long-term goal is to capture 1 percent of global annual carbon dioxide emissions by 2025.

Along with cutting fossil fuel use to zero, removing carbon dioxide from the air is increasingly seen as one way to stop the long-term buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Carbon removal and storage coupled with drawing down fossil fuel use is called “negative emissions.”

Time is running out to perfect the various methods of capturing carbon dioxide and permanently storing it. Research shows that atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations will increase to the point that 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) of global warming will be inevitable within the next 22 years. Scientists consider that level of global warming dangerous, and the goal of the Paris climate agreement is to stop global warming before that limit is reached.

The technology to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, including planting new forests and building facilities that directly remove and capture climate pollution from the air, is in its infancy. It has never been tried at a large scale, and nobody knows if it can be used worldwide to remove enough carbon dioxide to slow warming.

The Climeworks plant represents the beginning of an industry that is attempting to perfect the technology. Other companies, such as British Columbia–based Carbon Engineering, are also working on direct-air capture plants that will commercially suck carbon dioxide from the air.

Sabine Fuss, a sustainable energy researcher at the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change in Berlin who is unaffiliated with Climeworks, said that the company’s direct-air capture plant is the first of its kind to operate on an industrial scale.

“It’s important to note that they will not be permanently storing the CO2 that will be captured,” she said. “Instead, it will be used for greenhouses, producing synfuels, etc. No negative emissions will be generated.”

Negative emissions can only occur when the captured carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere and then locked away forever, she said.

But Climeworks cofounder Christoph Gebald said the company’s carbon capture plant can be used for carbon sequestration.

“Highly scalable negative emission technologies are crucial if we are to stay below the 2 degrees C target of the international community,” he said. “The DAC (direct-air capture) technology provides distinct advantages to achieve this aim and is perfectly suitable to be combined with underground storage.”

Gebald said his team installed 18 carbon dioxide collectors on the roof of a garbage incineration plant outside Zurich. Powered by wasted heat from the incinerator, the collectors use fans to suck ambient air into filters, which absorb carbon dioxide. The filters are heated and the carbon dioxide is removed and piped into nearby greenhouses, which will use 900 metric tons of captured carbon to grow crops each year.

The captured carbon dioxide could also be used to manufacture transportation fuel, carbonated soft drinks, and other products, Gebald said.

In order to meet the goal of removing the equivalent of 1 percent of annual global carbon dioxide emissions, 250,000 similar direct-air capture plants would have to be built, Gebald said.

Future direct-air capture plants will cost up to $400 per metric ton of captured carbon dioxide to operate, Gebald said, with carbon sequestration adding an additional $10–$20 to that cost per ton.

Glen Peters, a researcher at CICERO, a climate research organization in Norway, said he is not closely familiar with Climeworks, but said it will be impressive if the company can meet its goal to capture 1 percent of global carbon emissions, but only if it can be stored. He said operational costs need to fall to about $100 per ton of captured carbon for the technology to be scalable.

Some carbon removal technology is controversial because some methods involve planting new forests and forcing large-scale changes in the way land is used, possibly displacing people and the farms they rely on to grow their food.

Peters coauthored a paper published last year warning that staking the future only on negative emissions technologies presents a “moral hazard” because they’re unproven, there is a substantial risk that the technology can’t be scaled up, and it may allow policymakers to think that weaning humanity away from fossil fuels is not urgent.

When asked if Climeworks is participating in a morally hazardous climate strategy, Gebald said that scientists are certain that global warming can only be addressed if global carbon dioxide emissions drop to zero.

“We feel there is no moral hazard,” he said. “The only way we can achieve this is by using all means we have available.”

Both getting rid of fossil fuels and directly capturing carbon dioxide from the air are necessary to solve climate change, Gebald said.