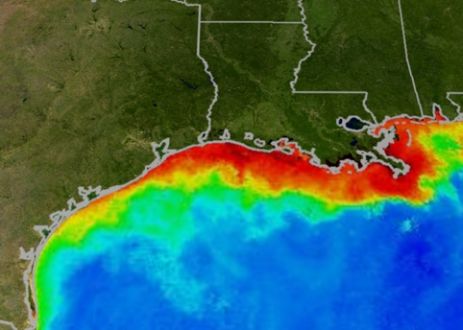

A satellite view of past Dead Zone in the Gulf: The red areas show how a vast, nitrogen-fed algae bloom has risen, blotting out most sea life underneath.(NASA)The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration just released a report that contains even more bad news for the Gulf of Mexico. This year’s Gulf Dead Zone will be unusually large — and that’s without accounting for any impact from the ongoing oil spill.

A satellite view of past Dead Zone in the Gulf: The red areas show how a vast, nitrogen-fed algae bloom has risen, blotting out most sea life underneath.(NASA)The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration just released a report that contains even more bad news for the Gulf of Mexico. This year’s Gulf Dead Zone will be unusually large — and that’s without accounting for any impact from the ongoing oil spill.

The Dead Zone refers to an annual oxygen-depleting algae bloom in the waters off the Gulf Coast. Krista Hozyash recently described its origin and impact in detail for Grist’s series on nitrogen, and Grist’s Tom Philpott summarized its cause in a post from the early days of the spill:

Every year, millions of tons of synthetic nitrogen and mined phosphorous leach from Midwestern farm fields and into streams that drain into the Mississippi. The great river deposits those agrichemicals right into the Gulf, where they feed a 7,000-square-mile algae bloom that sucks up oxygen and snuffs out sea life underneath. The bulk of this vast Dead Zone’s rogue nutrients comes from the growing of corn, our nation’s largest farm crop.

According to NOAA, the average size of the dead zone over the last five years has been about 6,000 square miles. Current models predict something between 6,500 and 7,800 square miles which, as the report observes, is “an area roughly the size of Lake Ontario.”

Study scientist and ecologist Donald Scavia says the likeliest outcome is 6,564 square miles. Though at the low end of the projected range, a Dead Zone that size would still make the Gulf’s top ten list, with the top five largest all having occurred within the last ten years.

“We’re not certain how this will play out. But one fact is clear: The combination of summer hypoxia [oxygen depletion] and toxic-oil impacts on mortality, spawning and recruitment is a one-two punch that could seriously diminish valuable Gulf commercial and recreational fisheries,” said Scavia, Special Counsel to the U-M President for Sustainability, director of the Graham Sustainability Institute, and a professor at the School of Natural Resources and Environment, in the release for the report.

An official with the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that 118,000 metric tons of nitrogen flowed down the Mississippi this spring. That’s an awful lot of excess fertilizer. And until we get more large-scale farmers to use far less synthetic fertilizer, we can look forward to ever larger dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico. That’s assuming, of course, that the oil spill leaves anything in the Gulf to kill.