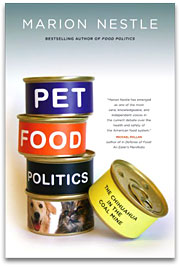

The contents of your dog’s bowl — kibble, kibble, more kibble — may not look that interesting, but to nutritionist Marion Nestle, they’re nothing less than a microcosm of the global food system. In her new book Pet Food Politics: The Chihuahua in the Coal Mine, Nestle (pronounced NES-uhl, no relation to the multinational) investigates the 2007 pet-food contamination scandal, at the time the largest consumer product recall in U.S. history. Companies withdrew nearly 200 brands of cat and dog foods from store shelves, and while the federal Food and Drug Administration eventually confirmed only 17 or 18 animal deaths, pet owners reported more than 4,000 fatalities.

Marion Nestle with Fantom.Photo: Larry CohenNestle delved into the roots of the recall in Canada, China, and the United States, even examining rumors that a Canadian woman had developed kidney disease after eating contaminated cat food (apparently false). Though Nestle is convinced of the need for regulatory reform and consumer vigilance in the worldwide pet-food production system, she emphasizes that most commercial pet food — fancy label or not — is safe and healthy. “I know people who feed their pets on the cheapest possible garbage food, and their pets do just fine,” she says.

Marion Nestle with Fantom.Photo: Larry CohenNestle delved into the roots of the recall in Canada, China, and the United States, even examining rumors that a Canadian woman had developed kidney disease after eating contaminated cat food (apparently false). Though Nestle is convinced of the need for regulatory reform and consumer vigilance in the worldwide pet-food production system, she emphasizes that most commercial pet food — fancy label or not — is safe and healthy. “I know people who feed their pets on the cheapest possible garbage food, and their pets do just fine,” she says.

But what does the pet-food contamination scare say about the safety of people food? Earlier this month, news broke that infant formula manufactured by the Sanlu Group and other Chinese companies was tainted with the protein-mimic melamine — the same industrial chemical found in the recalled pet food. The contamination, which is now thought to have killed four infants and sickened thousands of babies in China, has also turned up in liquid milk and other dairy products. Grist spoke with Nestle — who has “grandpets,” but no pets of her own — to learn more about the unexpected culinary connections between pets and people.

You investigated who knew what, and when, in this recall saga. Who bears the bulk of the blame?

You investigated who knew what, and when, in this recall saga. Who bears the bulk of the blame?

The blame started with some unscrupulous manufacturers in China who laced wheat flour with melamine — an industrial chemical — and sold it as wheat gluten. That was clearly fraudulent; a reporter for The New York Times interviewed farm-feed producers, and lots of people told him that they did this sort of thing all the time. They would have used urea, which was less toxic, except it was easier to detect. It was just a completely open secret in China that this kind of thing was being done.

Let’s give everybody the benefit of the doubt: I don’t think the Chinese realized how toxic [melamine] was. Probably they’ve been doing this for a very, very long time, and it never caused any problems before. But in this particular batch, the concentration of melamine was exceptionally high, and because of that, its byproduct (cyanuric acid) was also present. Those two chemicals together, at very low concentrations, can form crystals that block the kidneys of cats and dogs.

Then it unfolded that people in America didn’t know where their [pet-food] ingredients were coming from — which is understandable, because there were so many intermediates. The companies bought it from an American supplier, who bought it from a distributor, who got it from an importer who imported it from China. Wheat gluten is no longer produced in the United States, because it’s too expensive to make here. Everyone was looking for the cheapest possible ingredients and getting them from China, just like we get so many other things from China.

What else has changed in recent decades about how we make and distribute pet food?

The big shock in all this was the consolidation and centralization of the industry. Canned pet food is quite complicated to make, so once a factory is set up to make it, it’s easier to contract with that factory to make your recipe. The shock was that this one company in Canada, that nobody had ever heard of, had a factory in the United States that was making pet foods sold under 100 different brands — ranging from the least expensive to some of the priciest. They were all made at the same place with the same ingredients.

You write that contaminated pet foods are an early warning of the safety hazards of globalization.

We saw that right away in this case with [the blood thinner] heparin. It was exactly the same situation: A fraudulent ingredient was put in that tested like heparin but was not heparin, just like the fraudulent ingredient melamine was put into pet food because it tested like protein. That happened within just a few months [of the pet-food recall] — and it killed people.

There were photographs of the backyard factories [in China] that were making heparin that were just absolutely shocking. There was a photograph in The New York Times of this operation that was in this dirty room with pig guts hanging out of buckets. It was amazing — “Oh my God, injecting that into my body? I don’t think so.”

Are problems in the pet-food supply system also a direct threat to human food?

It’s impossible to separate the food supplies for pets, people, and farm animals. We already knew that from [genetically engineered foods], when things destined for animals got into the human-food supply.

The pet-food supply is linked to the human-food supply in two very important ways: One is that pet foods provide an outlet for the byproducts of human-food production, things that would otherwise have to be wasted or go into landfills or be burned. The other way is that surplus pet foods are fed to pigs and chickens. Who knew? I certainly didn’t.

In this case, melamine was fed to pigs, and pigs were found to be excreting melamine in their urine. The meat from pigs on that farm had already been sold and consumed. If [melamine] caused any problems [for humans], nobody knows anything about them. [If it didn’t], it was because of what the FDA charmingly refers to as the “dilution effect” — since nobody eats just pig meat, [the melamine] would be so diluted that it would be below the level that would be toxic.

What are some of the key changes you’d like to see in pet-food regulation?

I think [companies] need to have much more transparent labeling. They need to have calories on the label. Companies really need to be very clear about where their ingredients are sourced — they need to know, and they need to inform their customers. And they need to be paying very, very close attention. They need to test for foreign toxins; in the case of dry foods, they need to test for bacterial and biological contamination. They all should be produced under [Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point] plans, standard food-safety plans.

Are these things companies could effectively do voluntarily?

Some companies are doing them voluntarily, but I think much greater national regulation is needed. The pet-food companies complain that the rules are different depending on what state they’re in. Well, that is a silly way of doing things; national regulation is absolutely essential. And it’s not fair to ask companies [to act voluntarily] because it sets up an unequal playing field: One company is going to go to all the trouble of doing this kind of thing, and it’s going to cost them, and everyone else is going to behave badly. Although in this instance, the companies that really behaved well — and let their customers know about it — did not suffer the same hit in sales.

[My colleague and I] heard a food-safety official who consults with pet-food companies speak at a meeting, and he talked about the kinds of reasons that people in these companies gave him for not following standard food-safety procedures. They said it was too much trouble, that it wasn’t necessary, that nobody told them to do it — these were dog-ate-my-homework kind of excuses. So unless these procedures are in place and diligently enforced, problems are going to occur. We know this from the human food-safety issue — voluntary doesn’t work, desultory doesn’t work, casual doesn’t work.

Are these reforms similar to those you’d suggest for human-food safety?

For human-food safety, we need a farm-to-table, universal, federally administered food-safety system — preferably with one agency in charge. We don’t have anything like that. We have a piecemeal food-safety system that’s divided largely between two agencies, [the Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration]. There are shocking overlaps and gaps that people have known about for years and have been complaining about — we need a single food agency that will impose federal regulations farm to table. It would be very good for the food business, but food companies don’t see that.

Did the scope of the pet-food recall draw attention to problems with human-food safety?

Oh yes, definitely, everybody drew the parallel — and if they didn’t, there was immediately the heparin problem, and then there were tomatoes, or jalapeño peppers, or cilantro, or whatever came next.

So has any progress been made?

No. We’re in the wrong election cycle.