Nestled between two major highways, the Houston ship channel, and a Valero refinery, the neighborhood of Manchester stews in a witches’ brew of toxic chemicals. Houston, known as the Petro Metro, is home to a quarter of the petroleum refining capacity in the United States. An elementary school next to a chemical plant; a public park next to a refinery. These are the kinds of places that exist in Manchester.

The southeastern Houston community is brimming with industrial facilities — over a dozen, including oil refineries, chemical facilities, and a metal recycling plant. Like most of Houston, many of these hazardous facilities make up a large part of the local economy. And as many locals see it, they may also account for many of the community’s health problems.

Yvette Arellano, a community organizer for the Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services, told Grist they’ve heard local mothers give tear-filled accounts of their children suffering from constantly red eyes and unable to eat because of nausea from the fumes. Manchester residents are actually at a 22 percent higher risk of cancer than the overall Houston urban area, according to a 2016 report.

“The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality has two goals: economic health and public health,” said Arellano, “public [health] coming second.”

Manchester is not the only community bombarded with potentially harmful chemicals. According to a new report by the Environmental Justice Health Alliance, nearly 40 percent of the country lives within three miles of at least one of the 12,500 high-risk chemical facilities (federally regulated by the EPA’s Risk Management Plan Rule) in the United States. This area is what is known to some activists as the “fenceline” zone.

People of color and people at or near poverty levels tend to make up a higher number of these communities, facing disparate levels of exposure to toxic chemicals. And location matters when it comes to exposure — there are 11,000 medical facilities and 125,000 schools — which 24 million children attend — within “fenceline” zones.

“These communities have been paying with their health and well being,” said Michele Roberts, co-coordinator at the Environmental Justice Health Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform and a contributor to the report.

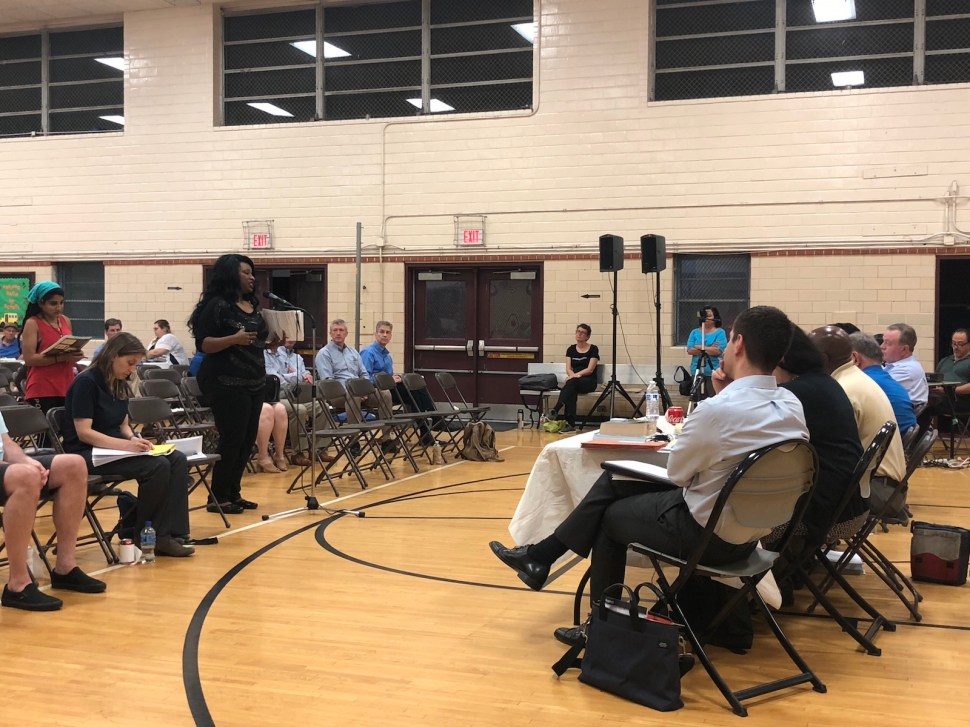

Residents of Manchester, Texas, line up to speak at a public forum about hydrogen cyanide emissions from the nearby Valero Refinery. Courtesy of t.e.j.a.s.

Back in Manchester, concerned residents are pushing for change. Over the past several months, residents and environmental justice advocates have been facing an uphill battle against the nearby Valero refinery. Local residents’ latest grievance is the company’s request to amend a permit that would allow the refinery to emit 452 tons of hydrogen cyanide, a known neurotoxin historically used as a chemical warfare agent, yearly into the community’s air. Though the poisonous chemical compound is illegal to store and illegal to produce, it is not illegal to emit.

Local exposure to the chemical is not new. The refinery has always emitted hydrogen cyanide, but activists say the new permit will allow for emissions of almost nine times the amount that is currently being released. Valero did not respond to Grist’s request for comment.

The refinery originally sought a permit that would allow for 512 tons of hydrogen cyanide emissions per year — a number they lowered after a public uproar at the first permit hearing back in June. But concerned residents say that’s still not good enough.

“It’s a slap in the face,” Yvette Arellano, a community organizer for the Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services, told Grist. “This should not be permitted at all.”

As Manchester residents grapple with a plethora of health concerns, momentum in the community is growing. Several undocumented mothers are spearheading a coalition against Valero behind the scenes, teaming up with environmental justice groups like t.e.j.a.s. Other Manchester residents are voicing their concerns at public hearings — around 50 residents and advocates were present at the first meeting earlier this summer.

To address the toxic air that may already be wafting into residents’ spaces. T.e.j.a.s. and members of the Manchester community are working together to roll out an air quality monitoring app, giving them the vital information they can use to push hazardous facilities to clean up their act. T.e.j.a.s. and many community members are also supporting the Toxic Alert Bill, which would set up an emergency alert system for residences near chemical plants in the case of a spill or an explosion.

“Communities are taking their narrative into their own hands,” Roberts said. “They’re speaking for themselves and being supported by environmental justice collectives that can help them get what it is that they actually want and need for their community.”

According to Arellano, in the current fight over hydrogen cyanide emissions, Valero might seek an exception so that they do not have to report that they’re even emitting the chemical. Manchester residents are now calling for more information in order to keep refineries, as well as chemical and storage facilities, accountable. Arellano says that though some residents want to leave the community, others simply want the plants to close.

“The residents were here first,” Arellano said. “This is their community.”