If you are unconvinced that food waste is a problem, then there are plenty of boggling stats to make you come to Jesus: The United States spends $218 billion a year producing food that nobody eats — amounting to 40 percent of all food grown. We devote roughly 80 million acres to grow food just for the garbage bin — an area three-quarters the size of California.

But what are we supposed to do? I assume you, like me, are already eating your onion skins (unsurpassable fiber!) and adding your coffee grounds to your smoothies? Or maybe I’m just getting a little eccentric after hearing all the anti-food-waste messages without any concrete plan for action.

That’s why I was excited to see the pragmatic, step-by-step plan just released by the nonprofit Rethink Food Waste Through Economics and Data (ReFED). It looks like a clear-eyed assessment of the challenge, along with a realistic agenda for tackling it. Their plan aims for a 20 percent reduction in food waste as a first step, resulting in a drop of 18 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions per year, according to ReFED’s estimates. That’s like switching off four coal power plants every year.

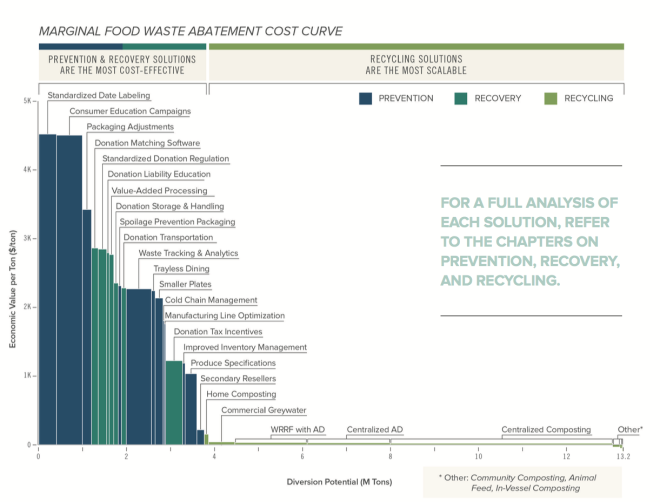

The ReFED report is 91 pages but basically boils down to this one chart.

The vertical axis is the amount of money we’d save by making ReFED’s changes and the horizontal axis is the amount of waste each strategy could prevent. Over on the left side of the chart, we have methods that would save a lot of money and cut a lot of emissions for each unit of food. On the right you see methods – composting and digestion — that could divert a lot of food waste from dumps but with a much lower bang for our buck.

Prevention and recovery

Look closely at the tall bars on the left. They’re methods for preventing food from ever getting tossed — standardized labeling and education.

The current state of labeling in the U.S. is crazy. There’s no federal standard, so 19 states have arbitrary rules that force stores to trash perfectly good food. In Montana, for instance, stores must dump milk just 12 days after it comes out of the cow — long before it goes off, a vintage that Californians and Texans buy without a second thought. In addition, about 20 percent of consumer waste comes from people throwing out unspoiled food because they worry that eating something past its “best by” date is unsafe. How do we change this wasteful behavior? Through education. It’s Walmart running videos at checkout lines that tell people how cutting waste saves money. It’s the NRDC launching a series of TV spots with the AdCouncil.

It uses a lot of natural resources to get food from farm to fork: You grow the wheat, ship it, grind it, turn it into pasta, ship it again, display it under lights in a supermarket, heat it on the stove and then … toss it. If we eat more of the food that makes this whole salmon-like journey — rather than throwing it out and buying more — it saves a lot of money and a lot of energy. That’s why the “prevention” and “recovery” techniques are so much more efficient than “recycling.” Avoiding the extra farming, processing, and transportation makes prevention and recovery two to 10 times better than recycling, in terms of greenhouse emissions, according to ReFED.

Recycling

To cut food waste measured by the ton — rather than measured in wasted money and energy — we also need to recycle. Composting and feeding waste to anaerobic digesters (turning waste into energy — “Centralized AD” on the graph) could keep the most food out of landfills. If this plan to cut food waste 20 percent is like shutting down four coal power plants a year, all this composting and digesting counts for one of those four coal plants.

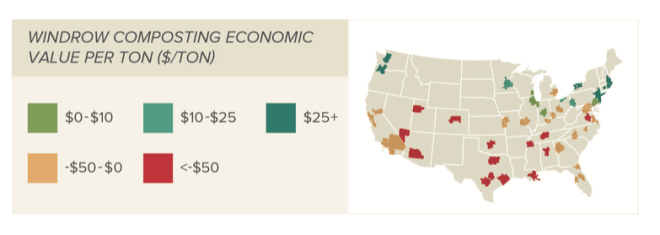

Sending trucks out to pick up tons of this rotting swill is expensive. In some parts of the country — particularly in the north where disposal costs are high anyway — centralized composting still makes a lot of sense.

Making it happen

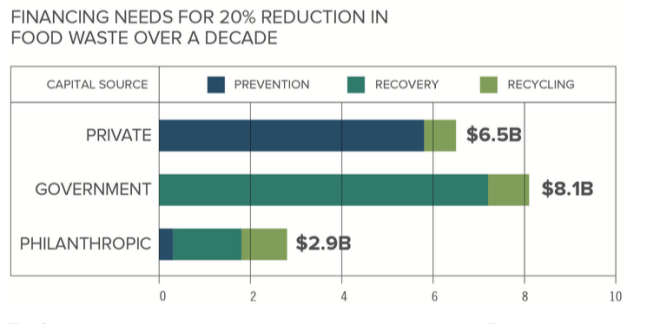

So how do we do all this? Through legislation, education, and innovation. That takes money: $18 billion total, spread over a decade. The report lays out how that spending might be divvied up. The biggest chunk — $8 billion from the government — would mostly go to tax rebates for food businesses that give unwanted leftovers to hungry people. It’s a lot of money for a relatively small diversion of waste, but it has the added benefit of improving social welfare.

I’ve seen lots of interesting ideas for cutting food waste. I haven’t seen many attempts to prioritize them. ReFED has collected all the ideas into one place and figured out which are most likely to work. An anti-smoking-style public education campaign? Thumbs up. Better labels? Check. But feeding waste to farm animals might not be worth the effort. In other words, keep eating your carrot tops, but feel free to toss those onion skins — unless you’ve developed a taste for them.