This story was originally published by High Country News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

If heat is the enemy, Marcela Herrera thought she was ready for battle last summer at her family’s north Los Angeles apartment.

Old air conditioner units chugged away on windows in three rooms. Extension cords snaked into box fans on the floor, positioned along a hallway to push cooler air towards warmer spots. Bamboo shades, bent blinds, and curtains beat back the sun.

But none of that prevented her eldest son, Edwin Díaz, from getting a nosebleed each time a heatwave crested over the family’s dense working-class neighborhood. And as outdoor temperatures climbed into the 90s, the 17-year-old suffered painful, debilitating migraines. The family doctor recommended that he try to stay cooler for the sake of his health.

Western communities, including Los Angeles, are aware that urban heat is a serious and growing threat to public health, and the warming climate only increases the problem. “It’s not as visible as other catastrophes, but the implications can be far reaching,” says Elizabeth Rhoades, who works on climate issues in Los Angeles County’s Department of Public Health.

Predictions are for longer, more frequent, and more severe heat events throughout the Southwest, especially in Los Angeles and Phoenix. Studies in the last decade suggest that heat especially impacts very old and very young city dwellers, poor neighborhoods, and those without central air conditioning: people like Edwin Díaz and Marcela Herrera. But researchers are still learning about how people are affected by excessive heat in the places where they spend most of their time — inside their homes. Few policies exist to protect the most vulnerable, and doctors say the conditions are poorly tracked.

Heat is sneaky. It worsens pre-existing conditions, such as heart and lung disease, kidney problems, diabetes, and asthma, more often than it kills directly. “People end up going to the hospital because heat affects their health, makes their asthma worse, or something worse,” says David Eisenman, a professor of medicine and public health at UCLA. “But it’s not technically coded as that in the records. It’s coded as ‘worsening asthma.’ So we really undercount the number of cases where heat is a factor.”

And urban heat is layered. Los Angeles is as much as 6 degrees F hotter than surrounding areas because of what’s called the “heat island effect.” Sprawl defines not just heat islands but what some call an archipelago of high temperatures across modern urban areas. Geography, wind patterns, tree cover, and concrete all work to create hotspots where temperatures are higher and air pollution is worse. In fact, climate models suggest that Herrera’s San Fernando Valley neighborhood, far from ocean breezes, will warm 10 to 20 percent faster than the rest of Los Angeles.

“There’s been this assumption that we can all cool off somehow. And in some ways that might have been true 100 years ago,” Eisenman says. “We don’t have access to the natural cooling environment like we did before.”

The landscape’s cooling elements disappeared long before Edwin Díaz and his mother arrived in the valley. Their Pacoima neighborhood derives its name from the Native Tongva word for a place of running water. (These days, the now concrete-locked Pacoima Wash, a flood-control channel, is often dry.) After World War II, the neighborhood boomed when developers marketed boxy homes to African Americans shut out of other parts of the valley by racial covenants.

Today, Pacoima is overwhelmingly Latino. And its single-family homes have produced a complex urban density, says Max Podemski, planning director for the community advocacy group Pacoima Beautiful. Lawns have given way to paved-over yards. Second-dwelling units, divisions within ranch homes, and modified garages can house several families together.

“That’s just totally ubiquitous here,” Podemski says. And these converted dwellings, uncounted and unpermitted, may or may not have insulation or air conditioners or windows to catch a breeze: “The city just doesn’t have data about it.”

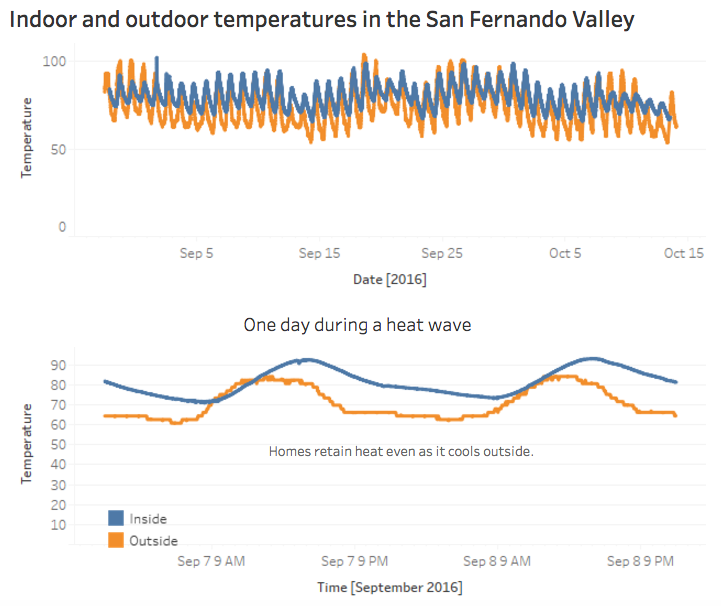

To understand more about how heat moves through Pacoima housing, last summer I built small electronic sensors to record dozens of heat and humidity measurements an hour, during parts of August, September, and October: the hottest months in Los Angeles. One sensor went in Edwin’s bedroom.

In early afternoon, that sensor recorded temperatures equal to those recorded outside, at the weather station at Van Nuys Airport. Evening temperatures in Edwin’s room were up to 9 degrees F higher than outside.

Those results tell a similar story to what a group of researchers, community activists, and scientists found in about 30 homes equipped with similar sensors in New York’s Harlem last year. “Buildings have a memory for heat,” says Adam Glenn, the founder of AdaptNY and a member of the community climate change observation project, ISeeChange. In New York, old stone buildings hold onto thermal radiation, especially on higher floors, late into the night. “So the danger to people continues even when the heatwave is over.”

But the ways buildings respond to climate vary. In Herrera’s apartment, a lack of insulation, common in older California houses, may be the key factor. In the evening, she says, “We can feel the warmth in the walls.”

The blanket of heat smothering L.A. hasn’t escaped City Hall’s notice. Mayor Eric Garcetti has set an ambitious goal to lower the city’s overall temperature 3 degrees in 20 years. L.A.’s Office of Sustainability is studying where and how to deploy landscape-level cooling strategies, such as planting trees and developing cooler pavements. But it will take years to even know whether the goal is achievable.

In the meantime, renters like Herrera’s family battle excessive heat mostly alone. According to the Census Bureau’s National Housing Survey, half as many rental properties in Los Angeles have central air as do owner-occupied units. Coping costs money. In summer, Herrera’s power bill can be as high as $200 a month.

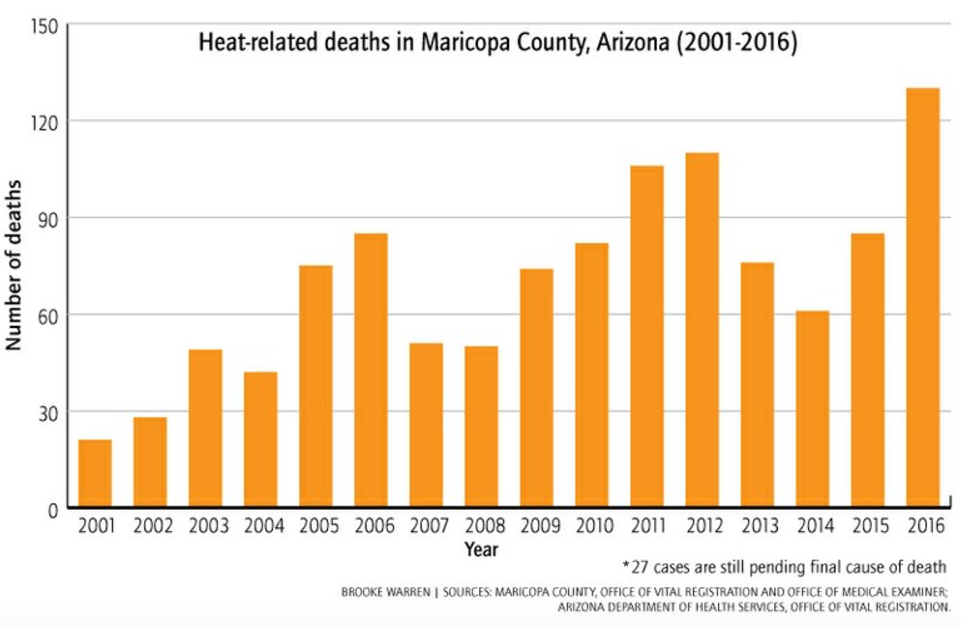

As temperatures rise in the Southwest, so do the stakes for city dwellers. In Phoenix, the Maricopa County Health Department has closely tracked heat-related death for more than a decade, producing an exhaustive report each year breaking down cases by age, ethnicity, economic background, and other risk factors.

Arizona State University researchers are working with Maricopa and Los Angeles counties to better understand how heat causes sickness and death, and how to counteract it.

“Many of us believe that no one should die prematurely because of heat, and there are significant public costs associated with heat just in the health-care sector alone,” says David Hondula, an ASU climatologist who studies heat impacts. Heat-associated deaths are climbing in Phoenix, but the reasons remain unclear. “If we can’t even answer that question, figuring out the best strategy to keep Phoenicians safe, or residents of Los Angeles safe, in a future that is expected to be warmer than it is today, would seem almost impossible,” Hondula says.

With summer coming, the Díaz-Herrera family has made some changes, insulating the ceiling of Edwin’s room and adding more air conditioners.

Paying for this has meant skimping elsewhere: fewer outings, no new clothes. Herrera worries that tight finances will force them to turn the air conditioners off. Still, “all the changes we’ve made are helping us,” she says. “It’s better to invest a bit more because health comes first.”

High Country News

This story was made possible with support from the Center for Health Journalism at The University of Southern California, while iSeeChange contributed heat sensor data.