Got a question for Umbra? Submit a question here.

In this week’s Ask Umbra, the call is coming from inside the house — and a messy house it is, at that.

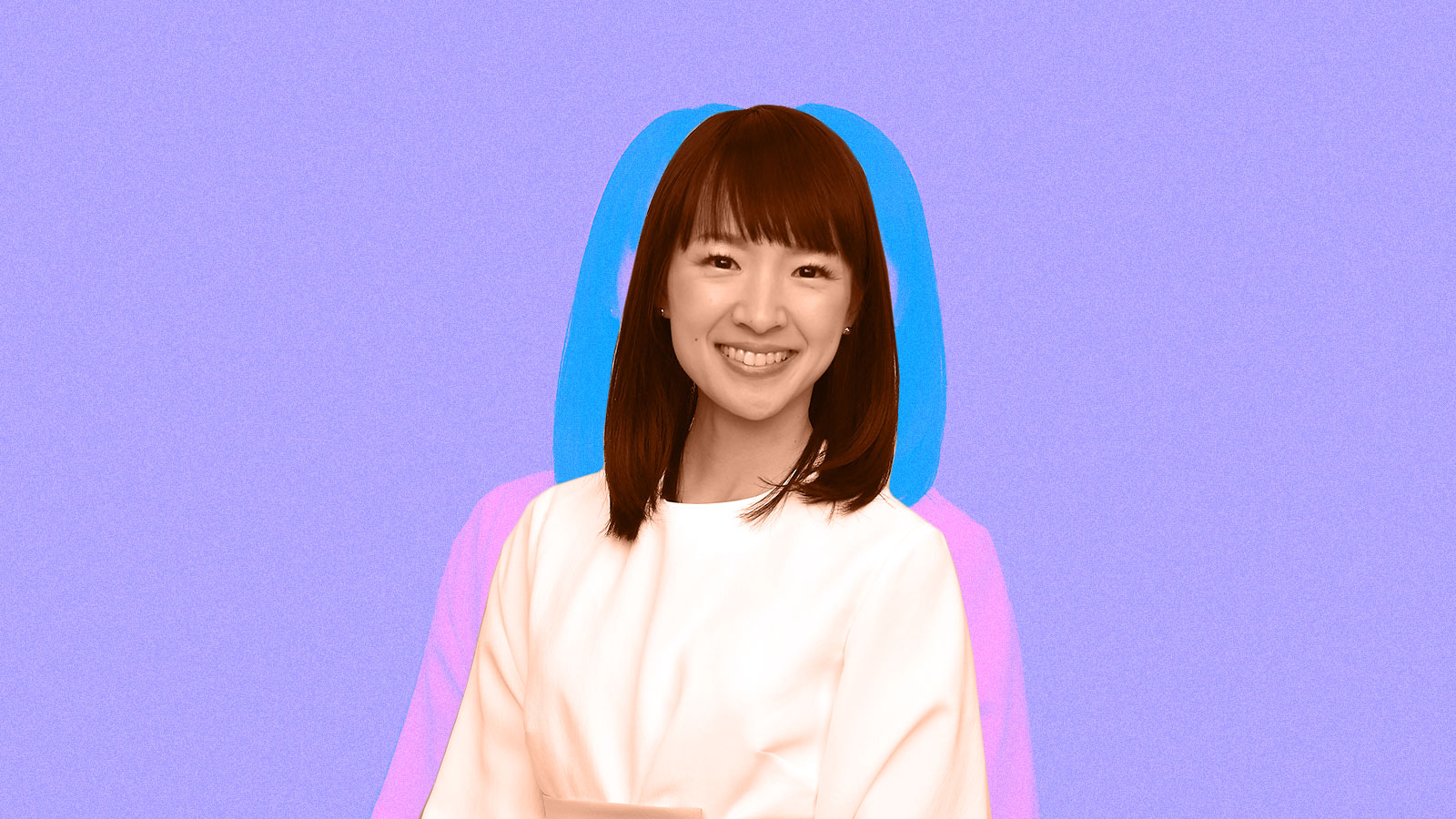

We at Grist are not above a good Netflix binge, and all the warm and fuzzy buzz around the newly released series Tidying Up with Marie Kondo had our curiosity piqued. The appeal is clear: Kondo helps families declutter their lives in typically 35-minute story arcs satisfying enough to push many directly from their screens to their closets to seek out “sparks of joy.”

But something felt lacking in the Kondo methodology. Annelise McGough, Grist’s growth and engagement editor, has been watching the home makeover reality show (OK one of our editors kind of forced her), and she couldn’t help but notice that it never really addresses the elephant in the (very cluttered) room: consumerism, the heart of environmental evil!

Umbra sat down with Annelise for a marathon of Japanese cleaning magic to try and figure out what was bothering her so much.

Caution: Minor spoilers ahead, if you care about the plot points of a cleaning reality show.

Annelise: I think my major issue is that it’s an entire show about dealing with all the things you own, but it never actually addresses why these people own so many things and the impact that has on the planet. In the second episode, Wendy, the matriarch of the Akiyama family, piles all of her clothes on the bed, as you do in step one of the KonMari method, and it literally creates a mountain of clothing that tops out at the ceiling.

Annelise: I think my major issue is that it’s an entire show about dealing with all the things you own, but it never actually addresses why these people own so many things and the impact that has on the planet. In the second episode, Wendy, the matriarch of the Akiyama family, piles all of her clothes on the bed, as you do in step one of the KonMari method, and it literally creates a mountain of clothing that tops out at the ceiling.

Eve: OK. So why do you think they own so many things?

Eve: OK. So why do you think they own so many things?

Because the pinnacle of the American dream is consumption; to buy whatever you want, whenever you want it, without the burden of having to think about its impact on the planet. We’re socialized into believing owning things is the key to happiness.

Because the pinnacle of the American dream is consumption; to buy whatever you want, whenever you want it, without the burden of having to think about its impact on the planet. We’re socialized into believing owning things is the key to happiness.

I definitely agree. I think the best encapsulation of that is in the seventh episode, with the couple Mario and Clarissa. Mario is the son of Guatemalan immigrants, and he has a really hard time parting with all the things that he’s been given by his family (a windbreaker his dad, who was jobless at the time, managed to buy for him on a Christmas) and the things he’s worked hard to purchase for himself (over 75 [!] pairs of shoes, many of them never worn). For Mario, being able to own lots of things is this expression of financial security, something toward which his family has been working.

I definitely agree. I think the best encapsulation of that is in the seventh episode, with the couple Mario and Clarissa. Mario is the son of Guatemalan immigrants, and he has a really hard time parting with all the things that he’s been given by his family (a windbreaker his dad, who was jobless at the time, managed to buy for him on a Christmas) and the things he’s worked hard to purchase for himself (over 75 [!] pairs of shoes, many of them never worn). For Mario, being able to own lots of things is this expression of financial security, something toward which his family has been working.

My friend just had a similar disagreement in real life with her fiancée, who grew up in an El Salvadoran immigrant family and survived Hurricane Katrina in Mississippi, about Konmari-ing their house. He didn’t see the point of getting rid of what he’d worked hard to build. “When you grow up how I did, the things you owned usually weren’t made to last and were disposable,” he told me. “So to me, it doesn’t make sense to dispose of perfectly functioning things.”

It definitely made me think about the privilege of Konmari-ing. If you grew up with plenty, getting rid of possessions doesn’t feel like a big deal because you’ve never had to worry about not having what you need. In our culture, possessions are security. A walk-in closet, stuffed with all the accoutrements of a “comfortable life,” is the ultimate goal. And then this small, Japanese lifestyle guru with really intense eyelashes comes in and tells you it’s all got to go because it’s actually meaningless.

Really intense eyelashes and really adorable babies who can probably fold the fitted sheets of their own cribs. But, right, the show doesn’t examine those underlying issues at all. It makes it seem like accumulating stuff is only problematic after it affects your personal life. Like, “Oh, it’s got to go because it’s causing tension between you and your partner” (like every couple in that show), or “your kids are picking up bad habits.”

Really intense eyelashes and really adorable babies who can probably fold the fitted sheets of their own cribs. But, right, the show doesn’t examine those underlying issues at all. It makes it seem like accumulating stuff is only problematic after it affects your personal life. Like, “Oh, it’s got to go because it’s causing tension between you and your partner” (like every couple in that show), or “your kids are picking up bad habits.”

But every episode I was waiting for someone to say, “Wow. How did this happen and why didn’t I think about it until now? What value did I think I would gain from another Nicolas Cage DVD? And even worse, I brought all this crap into the world and most of it will sit in a landfill or float in the ocean until forever!” That didn’t happen.

I noticed that in all eight episodes, every one of the subjects discussed their stuff in these almost siege-like terms. Like, “our stuff is imprisoning us.” Some actual quotes from the Konmari-ees I wrote down are: “We’re in a never-ending battle to fight the clutter;” the process will “force us to go through our stuff;” “we’re surrounded by all these things.” Like, the stuff has a mind and malignancy of its own. In almost every episode there was a room that the family just didn’t go into because the “stuff” had taken over. It’s a stack of sweaters, not the Spanish Inquisition.

I noticed that in all eight episodes, every one of the subjects discussed their stuff in these almost siege-like terms. Like, “our stuff is imprisoning us.” Some actual quotes from the Konmari-ees I wrote down are: “We’re in a never-ending battle to fight the clutter;” the process will “force us to go through our stuff;” “we’re surrounded by all these things.” Like, the stuff has a mind and malignancy of its own. In almost every episode there was a room that the family just didn’t go into because the “stuff” had taken over. It’s a stack of sweaters, not the Spanish Inquisition.

Exactly. You bought the stuff. You are not the victim of a tidal wave of BlueRays. I get that there’s a mental health aspect to all of this, and I’m not trying to lessen the legitimacy of people who have deep issues related to stuff. But Marie Kondo never says to anyone on the show, “In the future, you should buy less. Buying lots of shit you don’t need got you in this situation. Maybe you should consider therapy.”

Exactly. You bought the stuff. You are not the victim of a tidal wave of BlueRays. I get that there’s a mental health aspect to all of this, and I’m not trying to lessen the legitimacy of people who have deep issues related to stuff. But Marie Kondo never says to anyone on the show, “In the future, you should buy less. Buying lots of shit you don’t need got you in this situation. Maybe you should consider therapy.”

The piling up of stuff definitely created visible discomfort — the Konmari subjects admitted to being embarrassed by all the clothes and shoes that still had tags on them. But there is a difference between being embarrassed by money you’ve spent and feeling a sense of shame or guilt for the environmental impact associated with your consumption.

It’s true. I’d love it if she said explicitly, “Consumerism is a pox on your home and the Earth!” There are certainly plenty of opportunities for her to do so. But — not to imbue an international corporation complete with franchising opportunities with some grand environmental purpose that very well may not exist — I kept seeing the Konmari Konverts talk about how they were viewing their possessions differently. In the sixth episode, a clutter-weary dad tells his Toys-R-Us-obsessed kids that the family is learning how to “get rid of things, not buy more stuff, and be happy with what we already have.” That seems to me to be an entry point to a greener path.

It’s true. I’d love it if she said explicitly, “Consumerism is a pox on your home and the Earth!” There are certainly plenty of opportunities for her to do so. But — not to imbue an international corporation complete with franchising opportunities with some grand environmental purpose that very well may not exist — I kept seeing the Konmari Konverts talk about how they were viewing their possessions differently. In the sixth episode, a clutter-weary dad tells his Toys-R-Us-obsessed kids that the family is learning how to “get rid of things, not buy more stuff, and be happy with what we already have.” That seems to me to be an entry point to a greener path.

When I interviewed a bunch of Konmari-ites last year, who had been through the process, they reported that they were buying less because they had changed their understanding of possessions — of what they need and truly wanted in their lives.

And that’s kind of the first step to downsizing your life, which I believe is the most important step toward a more environmentally-conscious lifestyle. So I don’t know if she has to use environmental shaming, per se, to get her point across. When it comes to changing behavior (which is a fundamental part of fighting climate change) simply threatening people with big, hard-to-comprehend threats like the global trash problem can overwhelm more than motivate. Pointing out that someone literally cannot enter a room of their own house because it’s filled with sneakers they’ve never worn — I think that’s an easier wake-up call to process.

So: Is Marie Kondo saving the world one bloated guest room at a time? Let’s not put that on her tiny, cardigan-covered shoulders. But if the Konmari method permanently cures its devotees of consumerist behavior, I’d for sure watch that follow-up series. I have to say it would be a lot more interesting than the current one.