The Department of the Interior announced on Tuesday new guidance to help federal agencies strengthen collaboration with Indigenous Nations in the management of public lands, water, and wildlife. The new policy will support agreements designed to help tribes co-manage projects on public lands that make up 620 million acres divided among four major federal agencies.

For decades, Tribal governments have been fighting for a larger role in the management of public lands. Through unequal treaty agreements, and outright land seizures by the federal government, Indigenous Nations were removed, often violently, from their traditional territories which were then converted into public lands. Currently, federal agencies have a responsibility to provide services required to protect and enhance remaining Indigenous lands, resources, and governments in exchange for those expropriated territories.

The Department’s new guidance will help Indigenous communities deal with climate change, navigate limited water resources, and build sustainable food production, but is also a formalized recognition of historic injustices.

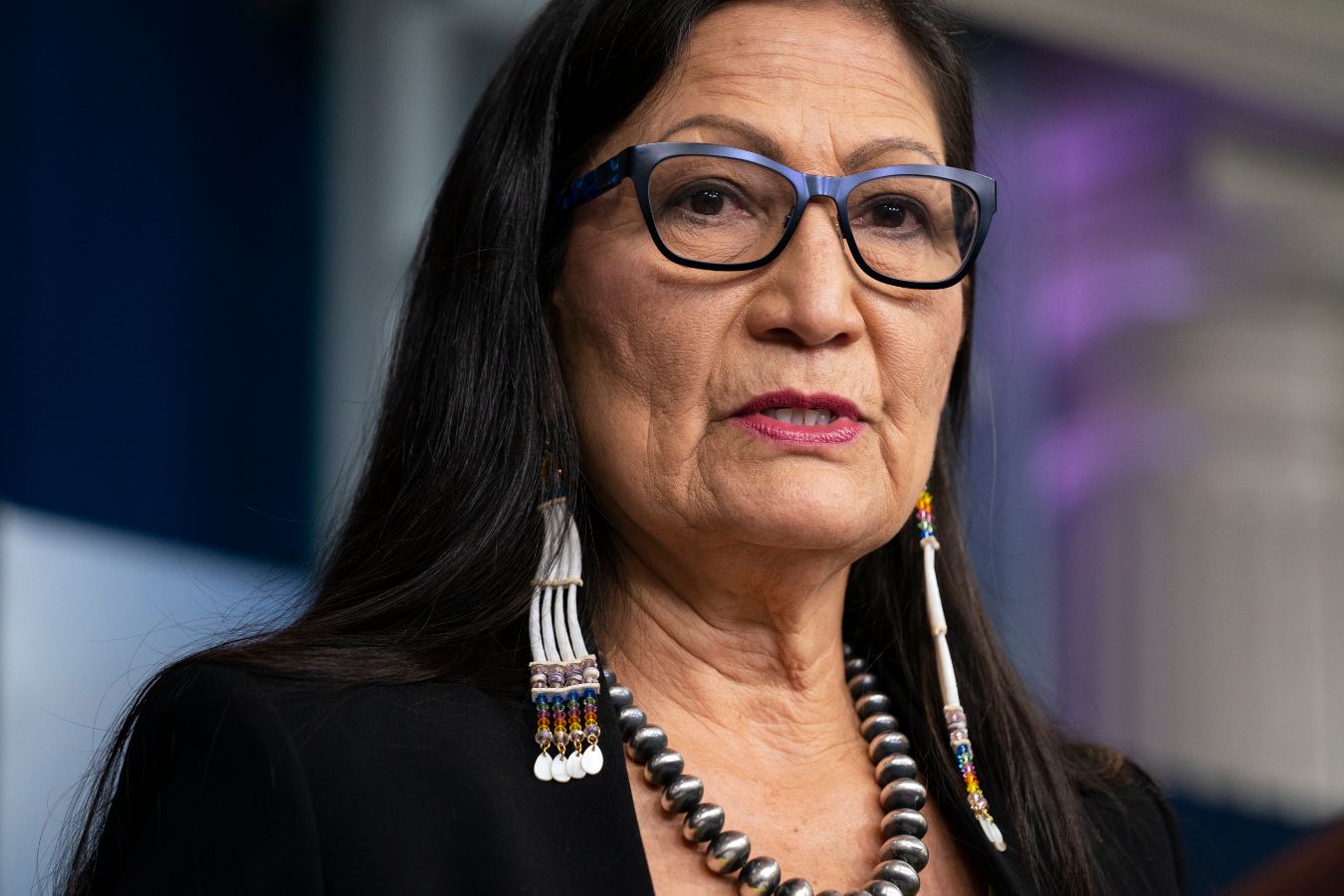

“By acknowledging and empowering tribes as partners in co-stewardship of our country’s lands and waters, every American will benefit from strengthened management of our federal land and resources,” said Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, in a statement.

In November 2021, the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and the Interior instituted the Tribal Homelands Initiative, which stated that agencies managing public lands and waters must consult and collaborate with Tribal governments as part of what are known as co-management policies. The principles of co-management tend to center on several key principles: the recognition of tribes as sovereign governments, their early and ongoing inclusion in any decision-making process, and the incorporation of Indigenous expertise in land management.

Increasingly, the principles of co-management and the incorporation of Indigenous knowledge in wide-ranging practices, from sustainable harvesting to fire management, have gained bi-partisan support. In a March 8 hearing by the House Committee on Natural Resources, Bruce Westerman, the ranking Republican from Arkansas, expressed his support for Tribal co-management policies. “We can learn a lot from tribes by the way they manage their land, in contrast to how the federal government does it,” he said.

Several co-management agreements between federal agencies and Indigenous communities over land and resource management have already been formalized since the November Tribal Homelands Initiative took effect. This April, the Rappahannock Tribe, whose territory lies on the eastern side of the eponymous river in Virginia, reacquired 465 acres from the Fish and Wildlife Service. In June, the Department of Interior transferred management of the Dworshak National Fish Hatchery in Idaho to the Nez Perce Tribe.

In June, the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service formalized an agreement with five Indigenous Nations to co-manage Utah’s Bears Ears National Monument, ending a nearly six-year battle to formalize the pledge that began under the Obama administration.

“We are being asked to apply our traditional knowledge to both the natural and human-caused ecological challenges, drought, erosion, visitation, etc.,” said Carleton Bowekaty, lieutenant governor of the Zuni Pueblo, in response to the Bears Ears agreement. “What can be a better avenue of restorative justice than giving Tribes the opportunity to participate in the management of lands their ancestors were removed from?”

But Raúl Manual Grijalva, the chair of the House Committee on Natural Resources and a Democratic representative from Arizona, has expressed concerns about how the federal government will track the number and extent of co-management agreements in place, as well as how agencies will be held accountable for their implementation. Earlier this month, Grijalva, sent a letter to the U.S. Accountability Office requesting an examination of federal land management agencies’ efforts to implement co-management agreements with tribal governments.