In the lead-up to the United Nations climate summit known as COP26, New York state officials made a landmark decision to deny permits for two proposed natural gas power plants after determining they would be inconsistent with the state’s greenhouse gas emissions targets and were not needed for grid reliability. The decisions, announced by the Department of Environmental Conservation, or DEC, last week, mark the first time the state has wielded its 2019 climate law to reject proposals for new electricity generation.

“We must shift to a renewable future,” DEC commissioner Basil Seggos wrote in a tweet announcing the decisions, tagging #COP26.

After the Biden administration’s recent failure to pass a law designed to move the power sector toward the goal of 100 percent clean electricity by 2035, the decisions in New York signal that state-level climate laws could prove to be a key alternative tool to get there.

New York climate advocates cheered the announcement. “This is a big deal. It’s a real turning point,” said Raya Salter, a senior advisor for the nonprofit WE ACT for Environmental Justice. “It really shows the power of the CLCPA,” she said, referring to the 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act. The law requires New York to have 100 percent emissions-free electricity by 2040, and to cut emissions across the economy 85 percent by 2050.

Both power plants would have replaced decades-old, heavily polluting facilities with new, more efficient gas-burning technology. One, proposed by Danskammer Energy, would have replaced a 1950s-era oil- and gas-burning plant in Newburgh, New York, which currently operates as a “peaker plant,” running only a handful of days each year during periods of high demand. The other, proposed by NRG Energy, would have replaced another peaker plant in Astoria, Queens, in New York City. The existing oil- and gas-burning plant, which began running in 1970, will be forced to shut down in 2023 due to new state regulations that limit the release of nitrogen oxides, pollutants that aggravate respiratory issues.

The news follows a similar decision by the DEC last year to reject a key water permit for the Williams Pipeline, a proposed natural gas pipeline, which the agency also found was inconsistent with the state’s climate law. In notices to NRG and Danskammer, Daniel Whitehead, the director of environmental permits at DEC, wrote that the state needed to accelerate its transition from all fossil fuels. “Constructing and operating a new fossil fuel-fired power plant accomplishes the exact opposite and perpetuates a reliance on fossil fuels,” the letters said.

In addition to citing emissions limits, the letters also noted that the Astoria plant would likely have a disproportionate impact on disadvantaged communities in the area — which the CLCPA also prohibits. Whitehead wrote that even if the facility satisfied the emissions requirements of the law, the agency could not approve the plant unless it “also satisfied this separate requirement” — sending a strong message about how the DEC will weigh environmental justice in future decision making. (The state is still in the process of defining “disadvantaged community”; the notice cited its interim definition.)

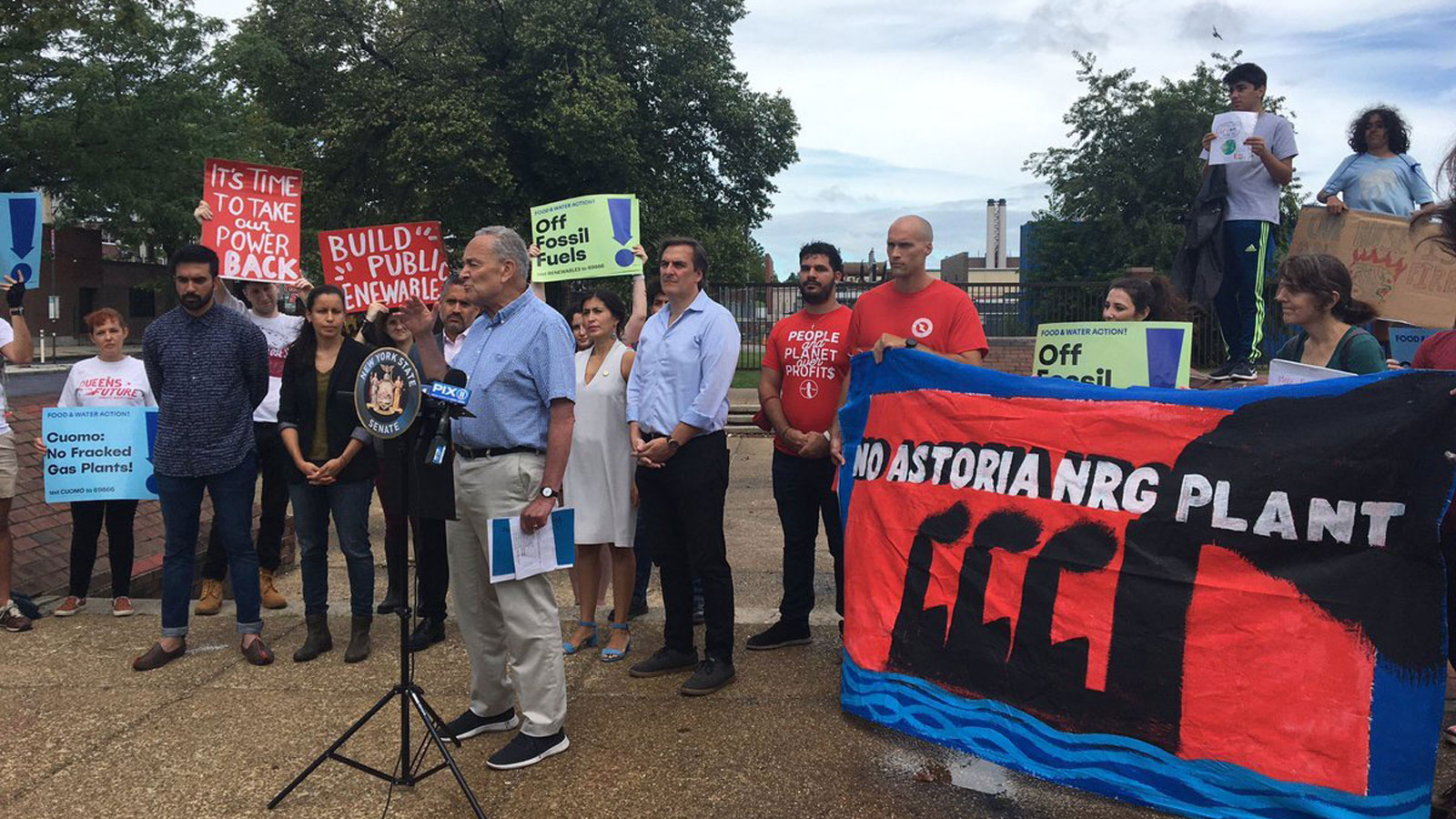

Stylianos Karolidis, a native of Astoria and an activist with the Democratic Socialists of America, was thrilled but not surprised by the DEC’s decision. He said there was overwhelming public opposition to the project. Karolidis helped run a campaign against the plant that resulted in more than 6,500 public comments and garnered support at every level of government, from district leaders all the way to U.S. Senator Chuck Schumer. “They did it because thousands of people were pressuring them to do it,” he said. “And they were making a huge, loud, impactful, publicly visible fight.”

Still, the result was not guaranteed. While the CLCPA put a goal of zero-emissions electricity into law, it did not say how the state should achieve it. New York is currently developing a “scoping plan” that will likely lay out whether solutions like natural gas power plants with carbon capture could be part of the mix, or plants that run on biogas or clean hydrogen. Some studies have found that these types of plants may be needed to complement wind, solar, and hydropower because they supply reliable, “always-on” power. But many environmental advocates deem them false solutions because they have not been proven economical yet and can perpetuate fossil fuel use and harmful pollution.

Both NRG and Danskammer argued that their proposals were in line with the state’s goals because they would be able to run the plants on hydrogen or biogas in the future. But DEC determined that those plans were “uncertain and speculative in nature.”

Justin Gundlach, a senior attorney at the Institute for Policy Integrity, a New York University think tank, said the decisions are likely to set a precedent and steer planning in New York’s power sector by “tamping down expectations” about whether the future promise of clean hydrogen can justify the development of natural gas plants today.

Danskammer did not respond to a request for comment. In a statement, NRG Energy vice president of development Tom Atkins said in a statement that the company was reviewing the decision. “It’s unfortunate that New York is turning down an opportunity to dramatically reduce emissions and strengthen reliable power for millions of New Yorkers at such a critical time,” he said.

The DEC’s decision might also have influence outside of New York state, as the natural gas industry is fighting to convince policymakers and regulators everywhere that natural gas can be part of a “lower carbon” future. According to a Sierra Club study from earlier this year, at least 32 electric utilities around the country are planning to build new natural gas plants this decade. That’s despite the fact that several of those companies, such as Dominion Energy, have announced goals to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

While many states have passed laws limiting greenhouse gas emissions, that has not yet stopped them from approving new natural gas plants. The only other example Grist could find of a state agency rejecting a proposal for a new natural gas plant due to climate goals did not actually stop construction of the plant. Last year, the New Mexico Public Regulation Commission rejected a plan by El Paso Electric Company to charge consumers $168 million to build a new natural gas plant, citing the state’s legally mandated goal of 100 percent clean electricity by 2045. But the plant was going to be constructed in Texas, so the company is moving ahead and is instead planning to sell the electricity solely to its Texas customers.

In California, the law requires the state get 60 percent of its electricity from renewables by 2030. As of 2020, the state was only about halfway there. The California utility commission in charge of approving power plants has sent mixed signals on whether it will accept proposals for new gas plants.

Activists in New York are hoping that the DEC’s permit denials mean that it will also deny permits to two other highly controversial fossil fuel projects. A natural gas plant that runs solely to power Bitcoin mining is seeking renewal of its air permit in Niagara County. An expansion of a liquefied natural gas facility in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, also has air permits pending.

Shay O’Reilly, a New York City organizer for the Sierra Club, said the decisions also felt like a marked change from when Governor Andrew Cuomo was in office. Cuomo resigned in August after being accused by multiple women of sexual harassment, and then-Lieutenant Governor Kathy Hochul succeeded him. “My hope is that this is a sign that our amazing officials at the State Department of Environmental Conservation are being given the reins to use their expertise in pursuit of the common good in our state,” O’Reilly said.