A new study released today finds that the Americans who live near hazardous chemical industrial facilities are disproportionately African American or Latino, are more likely to live in poverty, and have lower incomes and education levels than the national average. These trends accelerate rapidly as one gets closer to the “fenceline” areas nearest dangerous chemical plants.

A new study released today finds that the Americans who live near hazardous chemical industrial facilities are disproportionately African American or Latino, are more likely to live in poverty, and have lower incomes and education levels than the national average. These trends accelerate rapidly as one gets closer to the “fenceline” areas nearest dangerous chemical plants.

More than 134 million people live in danger zones created by about 3400 U.S. facilities that manufacture chemicals, produce paper, treat water, generate electric power, refine petroleum, or otherwise use or store hazardous materials. Millions more people work in or visit these areas.

The study examined the people living close to chemical plants and found:

- The poverty rate for the fenceline zones is 50% higher than for the U.S. as a whole.

- Average household incomes in the fenceline zones are 22% below the national average.

- The percentage of adults in the fenceline zones with less than a high school degree is 46% greater than for the U.S. as a whole.

- The percentage of Blacks in the fenceline zones is 75% greater than for the U.S. as a whole.

- The percentage of Latinos in the fenceline zones is 60% greater than for the U.S. as a whole.

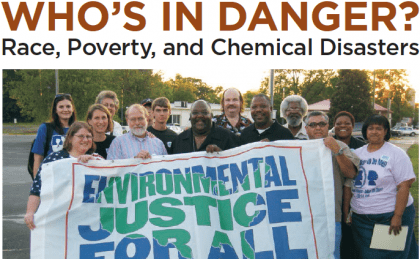

The study was produced by The Environmental Justice and Health Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform, a group of organization connected to the Coalition for Chemical Safety (in which I participate as an adviser to Greenpeace).

In the wake of the April 2103 West, Texas, chemical plant explosion, which killed 15 people and injured 160 more, President Obama issued an executive order directing federal agencies to improve the safety of our industrial chemical plants. The Obama Administration is now conducting a review of these issues.

There are serious risks that today’s chemical plants could unleash a catastrophic accident, like the 1984 pesticide plant disaster at Bhopal, India, which caused 20,000 deaths. In an average year, the U.S. Chemical Safety Board reviews some 250 high consequence chemical incidents involving death, injury, evacuation, or serious environmental or property damage.

There is also the possibility that terrorists could trigger a chemical plant attack in our country. In 2003, a government panel warned that chemical plants in the US could be al Qaeda targets. Media investigations have highlighted weak or nonexistent security at these facilities, with gates unlocked and chemical tanks unguarded. As a senator, Barack Obama referred to chemical plants as “stationary weapons of mass destruction spread all across the country.”

For years, our coalition has urged the government to take action to move chemical plants toward safer chemicals and processes. Now, Christine Todd Whitman, head of the EPA under President George W. Bush, and Lisa Jackson, who held the same job under President Obama, have each called for government to mandate safer chemicals. But wealthy chemical companies, like the ones owned by the Koch brothers, and their lobbyists have long used campaign contributions as weapons to block reforms, and they are still doing so today. Again, it was Senator Obama who said it best: “We cannot allow chemical industry lobbyists to dictate the terms of this debate. We cannot allow our security to be hijacked” by special interests.

Today’s study defines this struggle: on the one hand, some of the wealthiest Americans, like the Koch brothers, pressing Washington to stop reforms to make chemical plants safer; and on the other, the poorest, least powerful people in society at greatest risk of harm or death from these facilities.

President Obama needs to make the right choice to protect all Americans and our national security.

This article also appears on Republic Report.