During the past few weeks, the top of the world has been burning. Vast swaths of the Arctic, from Alaska to Siberia, are on fire, with scientific agencies breaking out the term “unprecedented” to describe the situation.

To the ecologists who work in the Arctic, this pyrotechnic summer is both weird and weirdly unsurprising: This is what can happen when you get lots of very warm weather. And their expectation is that this summer isn’t a once-in-a-lifetime fluke; rather, it’s indicative of rapid changes that could alter the fabric of Arctic ecosystems, unleashing even more billions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere.

While the Arctic is no stranger to summer fires, the sheer amount of activity right now is striking. Mark Parrington, a senior scientist with the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, who’s been tracking the fires via satellites, said that he spotted between 250 and 300 fire “hotspots” north of the Arctic Circle most days in July — five to six times more than he typically sees.

The geographic spread of the fires is also unusual, according to Merritt Turetsky, an ecosystem ecologist at the University of Guelph in Canada. While fire activity has been average this year in the Canadian Arctic, it’s been pretty severe in Arctic Alaska and Siberia, where more than 13,000 square miles of land — an area larger than Belgium — burned this week, prompting Russia to send out military forces to battle the flames. Several small fires have also popped up on the other side of the world in Greenland.

But perhaps the most important way 2019’s Arctic fire season has been weird is the intensity of the blazes and their associated carbon emissions. Parrington’s agency tracks “fire radiative power,” a measure of the heat output of fires. For both June and July, this fire power was the highest it’s been in the satellite record. And that’s led to some eye-popping carbon emissions: In June and July together, more than 140 megatons of carbon went up in smoke, Parrington’s latest analysis indicates. Not to pick on Belgium again, but that’s the same amount of carbon the country emitted in all of 2018.

It’s the intensity and persistence of the burn, along with these astonishing emissions figures, that prompted Parrington’s agency to describe the Arctic wildfires as “unprecedented” in early July.

Where there’s heat, there’s fire

Heat is what supercharged this year’s Arctic fire season. Globally, June 2019 was the hottest June on record. In parts of Alaska and Siberia where fires have raged, said Thomas Smith, an environmental geographer at the London School of Economics, temperatures were 8 to 10 degrees Celsius (15 to 18 degrees Fahrenheit) above normal. Alaska just rounded out its warmest month on record, and Greenland is currently undergoing a major heat-induced meltout.

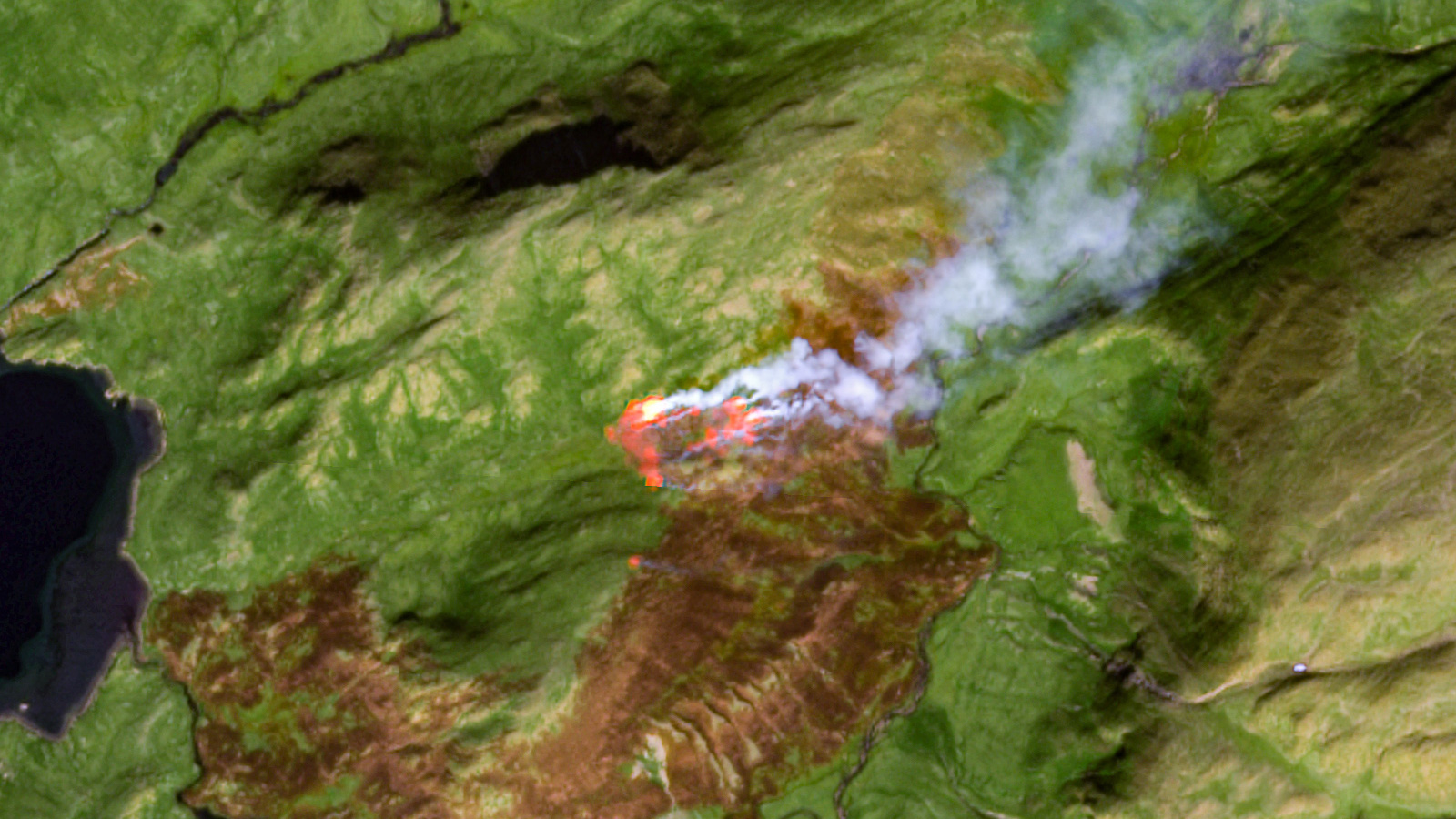

Satellite image of a wildfire in the Mirninsky District of the Sakha Republic, Russia on July 22, 2019. Pierre Markuse

The unusual warmth is drying out the mosses, shrubs, and conifers blanketing the Arctic’s boreal and tundra landscapes. It’s having an effect belowground, too. “The heat is drying out deeper into the soil, which means the duff layers lower down are much more susceptible to burning,” said Carly Phillips, a scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center on Cape Cod who studies carbon cycling in northern ecosystems. When lightning provides the spark, all of that stuff can burst into flames.

Smith’s biggest concern is the fires burning on peatlands — heaps of waterlogged, partly-decomposed organic material blanketed in springy sphagnum mosses. Under normal conditions that moss acts as a flame retardant, but when persistent warmth dries peatlands out, it can catch fire. And once a peat fire starts, it can smolder for weeks, eating its way through yards of fuel that accumulated over centuries.

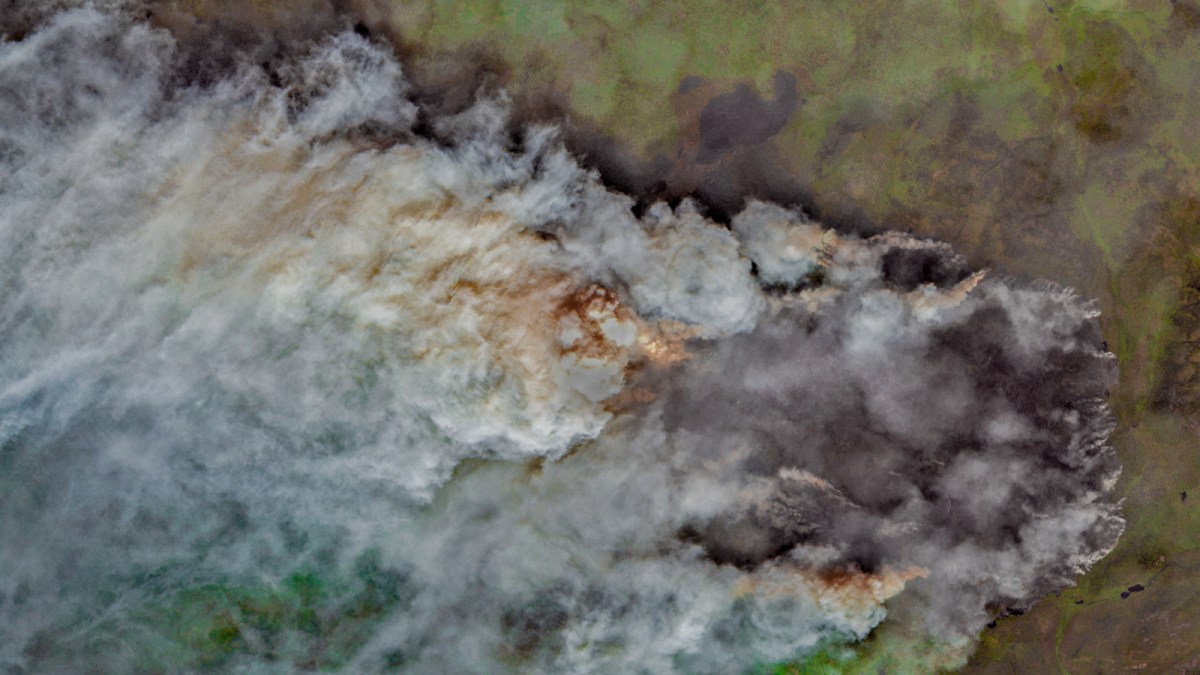

In Alaska, these have a name: zombie fires. “These are systems that’ll smolder for a long period of time and can reignite landscapes days, weeks, months, potentially years later,” said Mike Waddington, an ecohydrologist at Canada’s MacMaster University. Among this year’s Arctic fires, Smith has identified a few that, from satellite data, fit the profile of zombies — peatland fires that are long-lasting and emit telltale brownish smoke.

Peat, Smith pointed out, is the precursor to coal. Like its fossil fuel cousin, it has a devastating effect on the climate when it burns, releasing up to 80 tons per acre of climate-warming carbon. That includes up to ten times more methane than your typical flame-driven fire. Methane, you may recall, is a greenhouse gas with 25 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide over the course of a century.

The new normal?

The Arctic is already undergoing rapid changes due to rising temperatures. As hotter, drier summers cause fire season to intensify, that’ll only accelerate other transformations underway.

For instance, trees and shrubs are migrating north. Paleo-records from northern Alaska indicate that in past periods when the tundra hosted more woody vegetation, it burned more often. There’s also evidence that shrubs take root on burned landscapes more easily, suggesting a self-reinforcing feedback. Shrubs also tend to make Arctic landscapes darker, meaning they absorb more heat, triggering even more warming.

Waddington’s research indicates that when peatlands are drained, the trees start to grow bigger, sucking more water out of the ground and crowding out the flame-resistant mosses. So far, this work has mainly focused on boreal regions south of the Arctic. But Waddington expects a similar process could play out on wilder peatlands to the north as they warm up and dry out, making them more susceptible to catastrophic burns.

Fire has always been a part of the fabric of life up north. But how frequently and how intensely a landscape burns ultimately dictates what will flourish there — and how frequently fire will return in the future. That’s why fire seasons like 2019 matter to Guelph’s Turetsky — not because they break this or that record, but because they’re additional points on a worrisome trendline.

“We’re seeing these major fire events occurring more frequently,” she said. “We’re not getting a break.”