Can destroying a tropical rainforest be “sustainable”?

Well, according to a decision taken yesterday by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), the major industry-NGO body, this greatest of environmental crimes is now officially “green.”

Palm oil plantations have driven the destruction of more than 30,000 square miles of tropical forest in Indonesia and Malaysia alone, pushing species like orangutans and Sumatran rhinoceroses and elephants to the edge of extinction. It’s the biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Southeast Asia, and has propelled Indonesia to be the world’s third largest climate polluter behind only China and the United States.

Nonetheless, at its Extraordinary General Meeting in Kuala Lumpur, the RSPO formally rejected longstanding calls from member companies, scientists and nonprofit organizations to stop certifying as “sustainable” palm oil produced through deforestation and other environmentally damaging practices like destruction of ultra carbon rich peatland and use of highly poisonous chemicals like the notorious paraquat, which is linked to kidney failure, respiratory failure, skin cancer, and Parkinson’s disease.

On one level, of course, the RSPO’s action is an exercise in patently absurd Orwellian PR: If something produced through wholesale destruction of tropical rainforests is considered “sustainable,” the word has lost any meaning at all. But the decision is sadly symptomatic of broader challenges faced by sustainability certification efforts across a variety of different industries. These persistent challenges have led some to question the value or applicability of the fundamental model many companies have relied on to prove their environmental bona fides — and develop a new model based more on industry transformation than green niche production.

Indeed, the palm oil decision leaves dozens of major companies including Unilever, Kellogg’s, Dunkin Donuts, Colgate-Palmolive, Walmart, Carrefour, Cadbury, and others facing something of a supply chain and image crisis. These companies have all pledged to source RSPO-certified palm oil out of an understandable desire to ensure that their products weren’t driving destruction of the Earth’s tropical rainforests and other hyper-valuable ecosystems — and respond to demands from their customers and NGO campaigns that they take the very basic step of ending links to deforestation. Large banks Credit Suisse, Rabobank, Citibank, HSBC, and Standard Chartered also have policies aimed at channeling investment towards RSPO companies.

The RSPO’s action was such a blatant affront to basic environmental values that even the organization’s co-founder World Wildlife Fund, which has always defended RSPO even in the face of withering criticism, issued a formal statement saying that while it intends to continue engaging with the RSPO, it no longer considers RSPO certification sufficient for responsible companies.

Because the review failed to accept strong, tough and clear performance standards within the P&Cs [RSPO Principles & Criteria] on issues like GHGs and pesticides, it is, unfortunately, no longer possible for producers or users of palm oil to ensure that they are acting responsibly simply by producing or using Certified Sustainable Palm Oil (CSPO). Therefore WWF is now asking progressive companies to set and report on particular performance standards within the framework set by the new RSPO P&Cs.

Responsible growers are those that not only certify all of their palm oil production against the RSPO principles & criteria but who also take the following further actions: immediate public reporting of GHG emissions from existing and new plantations using Palm GHG;

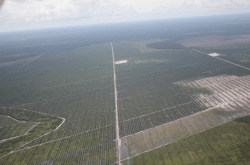

Aaron Fishman“sustainable.” Palm oil plantation on recently cleared peatland rainforest.

‐ for new oil palm developments: full implementation of the RSPO New Plantings Procedure and zero‐net land use emissions over a single rotation, which will exclude cultivation on peat‐soils and clearance of high carbon stock areas;

‐ for existing plantations and mills: significant annual GHG emissions reduction targets

‐ essential measures should include the treatment of mill effluent to eliminate methane emissions and the restoration of any plantations on peat at the end of the current rotation;

‐ an end to the use of pesticides that are categorized as World Health Organization Class 1A or 1B, or that are listed by the Stockholm or Rotterdam Conventions, and paraquat;

‐ only buying Fresh Fruit Bunches (FFB) from known sources, in particular no FFB originating from land illegally occupied or that is within any sort of designated or protected areas such as national parks;

WWF’s statement surprised many long time palm oil watchers, but the organization deserves enormous credit for sticking to its principles and making clear that companies cannot claim sustainability just by sticking an RSPO label on their product while continuing to destroy the Earth’s forests.

So what are responsible companies to do? Dozens have dived into the RSPO’s sustainability vat, only to float up saturated in palm oil and stinking of deforestation.

The good news is that RSPO is far from the only game in town — there are many options for sourcing deforestation free vegetable oil – and it’s now time for companies to take advantage of them.

Of course, coconut, soybean, canola and other vegetable oils generally have far fewer issues with deforestation, though responsible companies should investigate the specific supply chain for any of the commodities they use.

And the Rainforest Alliance’s Sustainable Agriculture Network standards not only go well beyond RSPO, but also create incentives for ecosystem restoration – and have been adopted by the Colombian organic palm oil producer Daabon. The Brazilian company Agropalma and New Britain Palm Oil are also considered leaders on reducing deforestation.

But perhaps most exciting is the commitment by Golden Agri-Resources (GAR), the world’s largest private sector palm oil producer, to eliminate deforestation from its supply chain following efforts by Greenpeace, The Forest Trust and other groups (full disclosure: I do some consulting work for TFT, though this article is my own).

As the grower of approximately five percent of the world’s palm oil, GAR can be an immediate large-scale source for deforestation free palm oil, period. Companies that buy from GAR or other responsible producers and traders are sending a signal that there is a demand for truly deforestation free palm oil, which will encourage other palm oil companies to raise their own standards.

The important point here is that what GAR and its fellow vegetable oil industry leaders are doing doesn’t rely on an amorphous term like sustainability that can be easily corrupted by cynical PR agents looking to greenwash wholesale ecological destruction. They’re saying something very simple: We don’t destroy forests, we don’t destroy peatland, and we don’t abuse human rights or community rights.

It’s very easy for the public, forest communities, journalists, civil society organizations and others to scrutinize them by that standard, and when they fall short, hold them accountable. There’s really not much room for fudging it.

This commitment that is simple and affordable to implement: most of the additional cost of RSPO-style certification comes from segregating the “sustainable” product from the “mainstream” product in processing, shipping, and sales – not from changing production practices. Indeed, a recent study by Timothy Fairhurst and David McLaughlin found that planting on degraded lands actually costs several hundred dollars less than planting on cleared secondary forests. With 6-10 million hectares of available degraded land in Indonesia and 60 million available in Brazil, there are massive opportunities for affordable, deforestation free production: companies just have to seize them. Certification can be a tool to help ensure that they’re meeting their commitments, but it’s no substitute for action.

In short, companies should stop proclaiming their commitment to “sustainability” from the stump, and just stop buying the products of ecological destruction. That’s what their customers demand, and what the Earth needs.