In the past two years, dozens of Republican and Democratic members of the U.S. House of Representatives have banded together in the name of tackling climate change. This bipartisan group, the Climate Solutions Caucus, now counts 90 members evenly split between the political parties. Its existence alone has raised hopes that political foes will soon put aside differences and take long-awaited action on climate change.

So a vote on the idea of carbon taxes this summer should’ve been an easy test for the caucus. No real proposal was on the table, just a resolution condemning them, introduced by Majority Whip Steve Scalise and supported by the Koch Brothers political network. It was a symbolic vote, more of a pledge of fealty to party leadership and the fossil fuel industry. Would-be dissenters had a convenient out: Prominent, old-school Republicans had publicly embraced carbon taxes a few weeks earlier as a market-friendly way to combat global warming. The stakes were low.

The result? A total of four Republican members of the caucus defended the taxes. The rest of the Climate Solutions Caucus voted against a climate solution popular with many Republicans.

“The caucus is a joke, or it would be were climate change not so serious,” RL Miller, co-founder of Climate Hawks Vote, said in a statement after the resolution passed.

As the caucus welcomes former climate deniers and would-be-EPA abolishers in the name of bipartisanship, progressive climate activists are calling for it to disband. They’ve labeled it the “peacocks” caucus, a place for vulnerable Republicans to gain environmental credentials without taking any risks — credentials that could come in handy in places like Virginia, Florida, and California, where more voters care about climate change than in the country overall.

“The requirements for admissions to the caucus seem to be that you need to be politically vulnerable, you have to have a pulse, and you have to be arguably human,” Miller said. The way she sees it, the caucus is “strictly political cover for vulnerable Republicans.”

The midterm elections will reveal whether that strategy worked. Of the 45 Republicans who have joined the caucus, more than half are either vacating their seats or fighting in tight re-election races. Will their membership help shield them from defeat? Or will the coming midterms simply expose the lack of bipartisan consensus on climate change, rendering the Climate Solutions Caucus and bipartisan climate action dead?

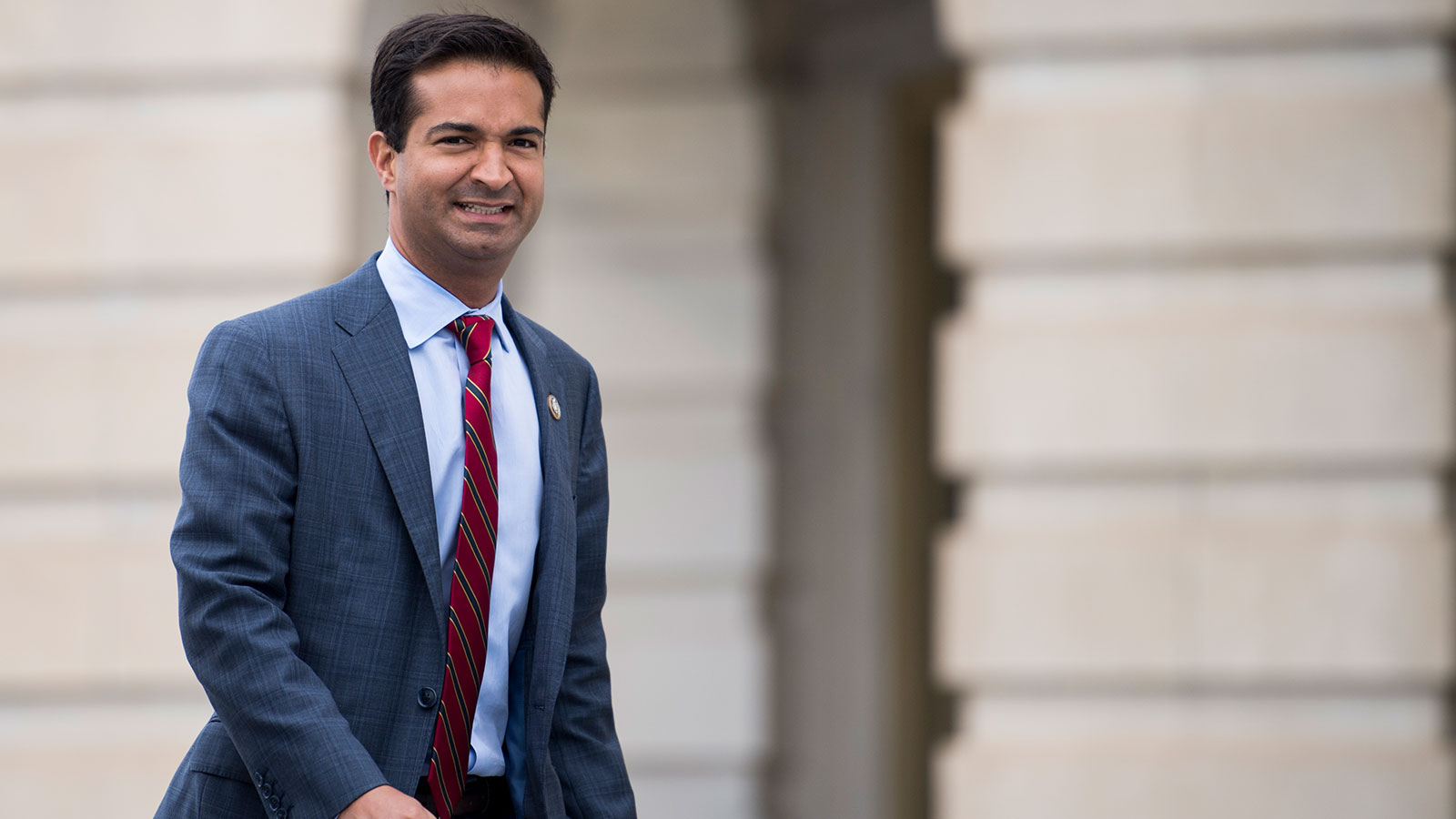

The Climate Solutions Caucus started in early 2016 as a partnership between two House representatives from Florida, Carlos Curbelo, a Republican (and member of the Grist 50 class of 2017), and Ted Deutch, a Democrat. Environmental groups and the media gave it a warm welcome.

The New York Times called the coalition “a promising baby step toward sanity.” My former employer, ThinkProgress, an outlet that has since become exceedingly critical of the caucus, hailed the group as “something amazing.”

But even as the caucus added members, it struggled to produce results. Instead, as President Trump began rolling back environmental regulations, the Republican half of its membership remained largely silent. A letter condemning the administration’s decision to repeal the Obama-era Clean Power Plan, for instance, garnered support from just three of its Republican cohort members. Last year, when Trump announced that he would withdraw the United States from the Paris climate agreement, six caucus Republicans publicly condemned the move. Four publicly applauded it.

Republican caucus members also supported the Trump administration’s sweeping tax-cut package last year, which included a provision opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling. A handful of them initially opposed that ANWR provision in a letter to Senator Mitch McConnell, the Senate majority leader. But then they ended up voting for it anyway.

“One of the big tests of the caucus’s sincerity to me was the tax bill,” Miller said. “They wanted their tax cuts so badly that they were willing to trade the Arctic for them. And that, to me, was a really big tell that the Climate Solutions people don’t care enough about the climate to stop this.”

And yet the caucus keeps growing. Its most recent Republican member is Francis Rooney, a Florida Republican who told constituents at a town hall last year that he wasn’t convinced that current sea-level rise is connected to human activity.

To be sure, it hasn’t been all greenwashing. The caucus’ biggest victory came in the summer of 2017, when its Republican membership helped defeat an amendment that would have stopped the Pentagon’s efforts to study climate change. The caucus often highlights that vote as evidence that it has had a tangible impact on climate policy. Deutch called the vote “proof that there is now a bipartisan majority in Congress of Members who understand that climate change is a real threat.”

Supporters of the caucus stress the importance of getting rid of the partisan rancor surrounding any discussion of climate change. To have 45 Republicans in Congress willing to put their names next to the words “Climate Solutions,” they argue, shows that the wall of inaction might be cracking.

Curbelo. Bill Clark / CQ Roll Call / Getty Images

“If you look two and a half years ago before the caucus started, you can probably count on one hand the number of Republicans willing to publicly acknowledge climate change and say that we need to be doing something about it,” said Steve Valk, director of Citizens’ Climate Lobby, the group that persuaded Curbelo and Deutch to start the caucus. “It’s easy to say that nothing has happened yet, but at the same time, we are a lot further along than we were a couple of years ago in terms of engaging Republicans on the issue.”

The caucus’ leaders don’t deny that the group can help give a Republican facing a close re-election race some environmental credibility to appeal to moderate voters. But that credibility, they argue, comes with increased scrutiny when it comes to environmental issues.

“When someone signs on to the caucus, they know what it’s about,” Curbelo said. “They know that members of the press and their voters, more importantly, are going to ask them questions and hold them accountable for both their membership in the caucus and their voting behavior.”

Take Barbara Comstock, a Republican incumbent from Virginia who’s fighting a tough re-election race against Jennifer Wexton, a Democratic state senator. Comstock represents a deep purple district in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., where concern about climate change runs anywhere from 3 to 7 percentage points higher than in the rest of the country. Numerous polls show Comstock trailing her challenger.

Before joining the caucus, Comstock’s name was rarely mentioned in discussions of environmental policies. Her voting record earned her a lifetime score of 5 percent from the League of Conservation Voters. (That’s on the opposite end of “pro-environment.”) But since joining the caucus last year, Comstock’s name has appeared in an ad by the Natural Resources Defense Council. The group urged her to vote “no” on the tax bill that opened up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling. She voted for the tax package. Then, she appeared on a list of critical votes to watch during the debate over the carbon tax resolution. She joined in that condemnation of carbon taxes as hazardous to the U.S. economy, too.

Despite her membership in the caucus, Comstock still consistently votes to undermine environmental regulations. She has voted to delay stricter ozone limits and to repeal a federal rule that would have prevented methane leaks from oil and gas operations.

Comstock. Bill Clark / CQ Roll Call / Getty Images

Corrina Beall, legislative and political director for the Sierra Club’s Virginia chapter, noted that Comstock joined the Climate Solutions Caucus “desperate to prove her climate bonafides.” But like other members, Comstock has little to show beyond her membership.

“Sadly, the supposed Climate Solutions Caucus has failed to live up to its name,” Beall said.

Comstock’s office refused multiple requests for interviews and comments. I reached out to every Republican member of the caucus for this article, and only six responded to a request for comment about why they joined the group.

Of the Republicans who responded, Curbelo is the only one who faces a tight re-election race. A poll out earlier this month from Mason-Dixon Polling, an independent firm that skews slightly Republican, showed Curbelo leading his opponent by a single point. Curbelo recently called people who connected Hurricane Michael to climate change “alarmists,” prompting a blowback from climate scientists and environmentalists.

Still, Curbelo has been one of the few Republican lawmakers to buck party lines when it comes to climate solutions. In July, following the House’s condemnation of a carbon tax, Curbelo introduced a bill that would have placed a $24 per ton price on industrial carbon dioxide. David Doniger, senior strategic director of the climate and clean energy program at the Natural Resources Defense Council, told the Guardian that it was a “breakthrough to see a serious Republican proposal.”

The question, then, is what kind of Republican vision will lead the Climate Solution Caucus if moderates like Curbelo are ousted come November. Of the four Caucus Republicans that voted against the resolution condemning a carbon tax this summer, three are locked in tight re-election races. The fourth, Florida Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, is retiring. When the dust from 2018 clears, it’s entirely possible that not one Republican member of the caucus would support a carbon tax. So what Republican vision would the caucus support?

One option could be to embrace the most right-leaning members of the caucus, like Rep. Matt Gaetz, a Florida representative expected to win re-election by a large margin.

“I joined the [caucus] because the Earth is getting warmer, climate change is real, and it is largely due to human activity,” Gaetz said in an emailed statement. “Many of my colleagues (particularly those on my side of the aisle) would rather spend their time arguing with a thermometer, but I don’t — I want to pursue real solutions to keep our planet and our environment healthy now and in the future.”

Gaetz’s concern for the planet is packaged with a distrust of big government. He’s perhaps best known in environmental circles for introducing a bill last year that would have abolished the EPA. When Trump announced that he would be withdrawing the United States from the Paris climate agreement, Gaetz cheered the move as “strong leadership.”

“Top-down edicts from the federal government often cause more problems than they solve,” said Devin Murphy, a senior legislative aide for Gaetz, explaining that his boss has an “affinity for free market solutions,” as well as local and state control rather than broad federal laws. “State and local decision-making is extremely important to us, because states know their needs better than Washington, D.C.”

It’s safe to say that Gaetz’s ideas for “real solutions” would look very different from those championed by most climate activists. And it’s not just Gaetz. The Republican party platform, for instance, calls for prohibiting the EPA from regulating carbon dioxide and touts “incentives for human ingenuity and the development of new technologies” to deal with “environmental problems.”

In theory, the basis for the Climate Solution Caucus is clear-cut: Any legislation that garners wide support from both parties stands a better chance of becoming law.

Champions of the bipartisan approach point to the cap-and-trade bill in 2009 as a cautionary tale, an illustration of the dangers of going it alone. The bill passed narrowly along party lines in the House but never got a vote in the Senate. In the following year’s midterm elections, conservative groups seized upon vulnerable Democratic members of Congress who had voted for cap and trade, likely contributing to the hefty losses the party suffered in red states.

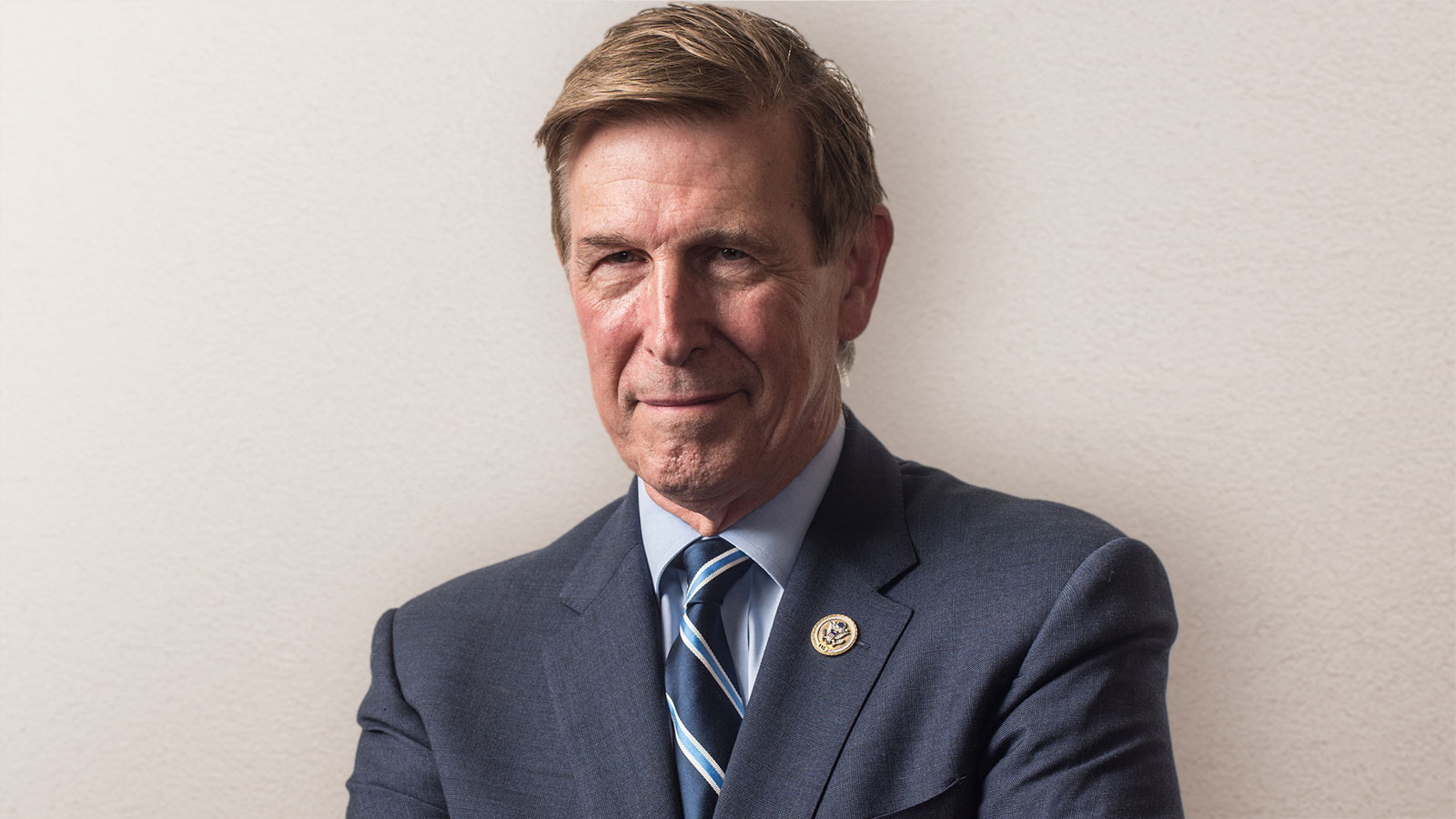

To avoid a similar fate in the future, Representative Don Beyer, Democrat from Virginia and a member of the caucus, argues that that the only way forward on climate is with a bill that can appeal to both parties — one with enough support that it doesn’t endanger members who vote for it. Beyer says he wants to work with Republicans to craft a carbon-pricing bill with the hope of introducing it next year.

“Imagine the Democrats take back the House, and we introduce a carbon-pricing bill,” Beyer said. “The stage will have been set, the relationships, the messaging, for many of the Republicans in the Climate Solutions Caucus to be co-sponsors.”

Beyer. Grist / Andre Chung for The Washington Post via Getty Images

In the current climate, however, it’s hard to imagine a carbon-pricing bill that could be palatable to both Democrats and Republicans. The most significant idea for climate action that has found favor with any conservatives was that proposal spearheaded by old-school members of the party, the former Secretaries of State George Shultz and James Baker, and supported by former Senator Trent Lott. It included a provision shielding oil and gas companies from legal liability related to climate change — a nonstarter for many environmentalists. The proposal also looks like a nonstarter for House Republicans; the House vote condemning the idea of a carbon tax came just one day after Lott publicly announced it.

“Bipartisan solutions to the climate crisis are absolutely a worthy goal — and are important for lasting change,” said Alyssa Roberts, press secretary for the League of Conservation Voters. “But with the current House majority beholden to corporate polluters, the best way to fight climate change is to elect a new, pro-environment Congress this November and a new president come 2020.”

Democrats haven’t controlled the House since 2011, and the party lacks a clear, unifying vision of environmental policy. Part of the reason is that they’ve spent recent years on the defense, working to block Trump’s environmentally unfriendly nominees and pushing back against regulatory repeal. Now the energy for climate action is coming from its younger, more progressive wing — exemplified by politicians like Representative Tulsi Gabbard from Hawaii. They’re more inclined to eschew carbon taxes and cap-and-trade programs and call for sweeping changes like a massive investment in green jobs and infrastructure and a commitment to climate and environmental justice. (Ideas unlikely to get GOP legislators excited.)

So if Democrats take the House, they’ll have to choose between following the path of the Climate Solutions Caucus and searching for common ground for compromise, or forging a path that energizes their own base without Republican support.

Either way, they won’t have time on their side. The recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change gives us just 12 years to get on track to avoid making climate catastrophes even worse: more heat waves and wildfires; longer droughts and punishing rainfalls; and much, much more.

“I think the ever-evolving changes in the environment that we see certainly pushes in the direction of trying to do something, eventually,” Beyer said. “The great fear, of course, is that we will do too little, too late.”