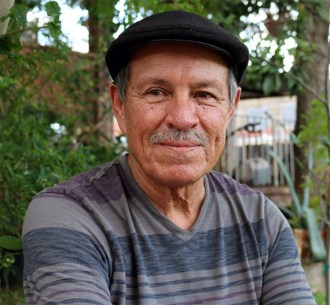

Juan Parras gives one hell of a tour of Houston’s east side. He’s charming and funny. Wearing a beret, he strikes an old-world look, like he might lead you to a cafe on a plaza. He doesn’t charge a fee for his services. After all, you’re on a “toxic tour,” and Parras is on a mission.

Parras grew up in 1950s West Texas. He remembers segregated schools, the restaurants that wouldn’t serve him, the unpaved roads, and the people who lived closest to the local refinery. Those experiences led him to a career as a social justice advocate. The resident of Houston’s heavily industrial east side has worked in a city housing department, for a union, for a law clinic, and on a campaign that stopped a PVC factory from being built in Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley.”

For the last decade, he has served as executive director of Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (better known as t.e.j.a.s.). Part of his work is leading tours past the heaping piles of scrap metal along Houston’s Buffalo Bayou and by Cesar Chavez High School, which opened in 2000 within a quarter-mile of three large petrochemical plants.

Parras can go all day, up and down the Houston Ship Channel to Denver Harbor and neighborhoods like Galena Park, Baytown, and Pasadena. Surely you’ve read about the Keystone XL pipeline and other controversial proposed projects that would carry oil from the Canadian tar sands to Gulf Coast refineries? Parras can show you where many of them would end.

The toxic tour sometimes concludes in the neighborhood of Manchester, a six-square-mile grid of streets where the petrochemical industry towers directly over small homes. Where, according to EPA databases, Valero Refining can produce up to 160,000 barrels a day of gasoline and other fuels. Where the Ship Channel Bridge, one of the busiest stretches of Interstate 610, carries tens of thousands of vehicles per day (along with their emissions) directly over homes. And where about 4,000 people live — more than 95 percent of whom are people of color, and 90 percent low income.

The cancer risk for residents of Manchester and the neighboring community of Harrisburg is 22 percent higher than for the overall Houston urban area, according to a recent report from the Union of Concerned Scientists and t.e.j.a.s. While the city works to overcome its image as a dirty oil town, these neighborhoods remain solidly dominated by the petrochemical industry. And despite the work of Parras and his team, the environmental and health issues that Manchester’s residents face are not gaining enough political traction to garner real change.

“Environmental justice issues become all too easy to grasp when you take people into neighborhoods,” Parras said when the Sierra Club awarded him its 2015 Robert Bullard Environmental Justice Award. So Parras gives the toxic tour over and over again, hoping that, eventually, people will listen.

In 2016, Houston was lauded for its “green transformation.” The D.C.-based nonprofit Cultural Landscape Foundation brought visitors from around the country to study new investments in the city’s parks, as well as an 150-mile network of trails alongs its bayous. Long the whipping boy of the urban-planning world, the fourth-largest U.S. city will soon have half a dozen signature parks designed by internationally known firms.

Yet Houston’s attempts to appear greener have thrown longstanding inequities into sharper contrast. Two-bedroom apartments in a downtown highrise overlooking Discovery Green park rent for more than $4,000. Seven miles east, chemical storage tanks dot the landscape around Hartman Park in Manchester, where nearly 40 percent of residents live in poverty.

Beyond financial disparities, the region’s signature industry inflicts a staggeringly disproportionate burden on east-side residents. According to the Union of Concerned Scientists’ report, the airborne concentration of 1,3-butadiene, which causes cancer and a host of neurological issues, is more than 150 times greater in Manchester and Harrisburg than in West Oaks and Eldridge, relatively affluent neighborhoods on Houston’s west side.

A Valero refinery sits directly across the street from the entrance to Hartman Park in Manchester, in east Houston. Courtesy of Yvette Arellano | t.e.j.a.s. & Union of Concerned Scientist Center for Science and Democracy

Adrian Shelley, director of Texas’s outpost of the watchdog group Public Citizen, describes Manchester and the neighborhoods that abut it as sacrificial lambs, where the situation is “unjust, offensive, cruel, racist, ridiculous, tragic, and costing lives.”

Juan Flores has lived in Galena Park, right across Buffalo Bayou from Manchester, since the age of four. One of his earliest memories, as a kindergartner, was “seeing all this white stuff on the cars” and thinking it was snow — a rare occurrence in Houston. He played in it until his mom yelled out, “Hijo, no! We don’t know what it is!”

When he would play with friends over in Manchester, he remembers smells that “were so unbearable you had to go inside.”

“Most of the people who live in the area, like my dad, work in the industry,” Flores says. “We are aware of the dangers. We can smell the chemicals.”

He recalls “his first explosion,” which happened in the nearby Pasadena neighborhood in 1989, when Flores was in sixth grade. He remembers seeing “a big mushroom cloud.” The so-called Phillips disaster — which was actually multiple explosions at the Houston Chemical Complex owned by the energy company Phillips 66 — broke the windows of his school. Twenty-three Phillips 66 employees were killed and 314 people were injured.

Flores was a member of the Galena Park city council from 2014 to 2016. He helped get an ordinance passed that limits the time trucks can idle on city streets, a substantial source of air pollution along the Ship Channel. The neighboring Jacinto City community adopted the policy, too.

According to Flores, truck drivers were at first upset with the new regulation. But he helped them understand the impact of running engines on the neighboring communities. “I told them, ‘Guys, it is your own kids,’” he says.

Local advocates say the only remedy for really helping the people trapped in Manchester and its toxic surrounding areas would involve a public buyout of their homes for the full cost of rebuilding their houses. (Market prices for Manchester-area homes are depressed by their hazardous neighbors). But even if residents were suddenly able to move to more pristine surroundings, Shelly says, doing so would disperse an entire community.

Meanwhile, it’s tough to argue that Houston — despite its new park-building boom — isn’t prioritizing industry over the health of its vulnerable communities. In May, Houston agreed to sell Valero several Manchester streets near its refinery for $1.4 million. The energy company will expand its footprint, adding auxiliary buildings and more parking for the facility.

In recent years, according to Parras, Valero has bought out some residents in a piecemeal approach. (Valero did not respond to requests to comment for this story.) But he still didn’t see the deal coming.

“I found out about the sale of the streets through the newspaper,” says Parras, who was taken aback after reading a Houston Chronicle article. “We are ignored.”

A spokesman for Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner says the “long-ago history” of the city has changed, as it’s made strides to reduce pollution and monitor potentially harmful substances coming out of industries. “If you look at the most recent history,” Alan Bernstein, the mayor’s communications director, tells the Texas Tribune, “you will find across-the-board improvements.

“Does Houston have poor neighborhoods and rich neighborhoods? Yes, as do all other cities,” Bernstein adds. “But currently Houston is blessed with having a government and a mayor who [are] focused on how to make opportunity and quality of life available to everyone as equally as possible.”

Policy that would help Houston control its pollution problem is tough to enact in a town dominated by the petrochemical industry. In 2005, a Chronicle investigation on industry-reported emissions spurred then-Houston Mayor Bill White to approach companies about voluntarily reducing air pollution — 1,3-butadiene, in particular.

In Manchester, Valero took the step of placing a sophisticated air monitor at its facility’s fenceline. Citywide, the impact of White’s entreaties on emissions appears to have been inconsequential, and the effort likely cost him in his subsequent campaign for governor.

An aerial view of Manchester. Google Earth

City-led initiatives are consistently challenged in courts by the Business Coalition for Clean Air, an industry-lobbying group that represents ExxonMobil and others. Last year, it convinced the Texas Supreme Court to strike down Houston’s Clean Air Ordinance, which was adopted during White’s administration.

The court ruled that the city does not have authority to enforce clean air regulations. During the last legislative session and the current special session, state politicians have put forward a range of bills using that and other pro-industry precedents to undermine the city’s ability to police environmental issues. Lawmakers have attacked tree-preservation ordinances, fracking bans, and policies to reduce single-use plastic bags.

A 2016 report by the Sierra Club, Public Citizen, and Texans for Public Justice found that the three state oil and gas regulators raised $11 million in recent years, 60 percent of which came from the industries they’re charged with monitoring. A 2017 report by the Environmental Integrity Project found that Texas penalizes only 3 percent of the illegal pollution releases reported by companies.

“In a different political environment, self-reported violations or reports of air-emission events would result in fines of $25,000 per day,” Shelley says. “But it is not done, even though the authority is there under the law.”

T.e.j.a.s. argues that the state should require chemical facilities to use safer substances, update their technologies, continuously monitor and report emissions, and avoid the construction of new facilities near homes and schools.

But Bakeyah Nelson, the executive director of Air Alliance Houston, says that putting such changes into effect “is tied to civic engagement and voting.” A real shift will happen, she explains, only when “elected officials reflect what the population looks like and vote in a way that is consistent with what people want, which is protection from environmental toxins.”

Last year, former Harris County Sheriff Adrian Garcia, a Mexican-American running on a platform that included environmental justice issues, challenged incumbent Gene Green, who has represented Texas’ 29th district, which includes Manchester, since 1993. Despite the district having a population that is 76 percent Hispanic origin, local and national Latino leaders backed Green, praising his consistent stand on immigration issues.

Green retained his seat with a message that voters were more concerned about the jobs that industry brings than curtailing its unchecked growth.

According to the Air Alliance’s Nelson, that economy-versus-environment framing is a false dichotomy. She says that greater regulation at a national level has coincided with continued economic growth and helped spur technological innovation.

Countering industry’s hold on the region would involve raising awareness among locals that they don’t have to choose between their health and their livelihoods, Nelson says. But the very fact that people choose to live in places like Manchester, which has been heavily industrialized since the 1970s, points to fundamental problems with access to safe, healthy, affordable housing, she adds.

“People need living wages so they don’t have to purchase homes that put their health at risk,” Nelson explains. “It is about environmental, health, and economic justice. All of those things are tied together.”

In some cases, little more than a fence separates Manchester homes from neighboring industry. Paul Hester

Houston-based and other Texas nonprofits — like Air Alliance Houston and Environment Texas — have recently banded together to try to bring the air quality around so-called fenceline communities (meaning they border the fences surrounding industrial facilities) into the public consciousness.

“Through storytelling and good science, we are informing people that we need better air for a healthier and prosperous Houston,” says Matthew Tresaugue, who manages the newly formed Houston Air Quality Media Initiative. The strategy includes amplifying the voices of residents, like Bianca Ibarra, a recent graduate of Galena Park High School, whose video PSA won a competition held by the media initiative and sponsored by the Environmental Defense Fund.

The collaborative effort is funded by the Houston Endowment, a charitable organization that gives out $80 million in grants yearly to local nonprofits. (Though the Endowment has fewer direct ties to oil and gas wealth than other local foundations, it’s previous president, Larry Faulkner, sat on the board of ExxonMobil while at the organization.)

Tresaugue stresses the need to move people to take action and put pressure on policymakers by connecting people in areas far from the Ship Channel to the challenges faced by residents of communities like Manchester, Harrisburg, Galena Park, Baytown, and Pasadena.

That’s something Juan Parras has been doing for years now. And while the new initiative gets its feet under it, he’ll continue his tours, giving them to anyone from students to fellow activists to public officials. That way, people can see and smell and reckon with what Manchester’s residents live with every day.

“This is considered the capital of the industry for gas and oil,” Parras says. “We learn that on a daily basis.”

This story was updated to add comment from the Houston mayor’s office. Additional reporting by Shannon Najmabadi of the Texas Tribune.