This story was originally published by Reveal and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Day after day, Keith Davis stood at the rail of the cargo ship, watching a fleet of rusty long-liners off-load tuna, marlin, and other fish.

His work as an observer for the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission was critical. On that ship off the west coast of South America, he was a vital watchman in the struggle to protect the world’s oceans from overfishing.

A 41-year-old musician and nature lover from Arizona, Davis was a veteran of many such voyages. He loved the Jacques Cousteau–like majesty of the high seas, the tinseled splash of dolphins and glassy-blue waves that rolled on restlessly from horizon to horizon.

This trip in 2015 was vexing. The fish being loaded onto the cargo ship were so heavily carved up that he struggled to identify them. He wondered whether fishermen on the long-liners might be trying to trick him, to disguise one kind of fish as another. Frustrated, he took pictures, asked questions and fired off emails to a federal fisheries biologist in Hawaii.

Keith Davis plays his mandolin on the bridge of the Victoria No. 168. Davis had once written a song about observers who died at sea: “Some say he’s lost. Maybe he’s been found.” Victoria No. 168

He also wondered about the crew on the cargo ship. Five hundred miles west of Lima, Peru, he was the odd man out, a scientific monitor and conspicuous informant in the company of mariners he did not know. Yet he carried no badge, no weapon. He had no way of signaling for help without going through a computer in the captain’s quarters.

On Sept. 10, the sky was the color of an old dishrag. The winds were light. A long-liner had just unloaded the last catch of the trip. Davis reported nothing out of the ordinary. But just after 4 p.m., the chief officer discovered something startling: Davis was not on board.

Alarmed, the captain ordered the crew to search the ship. They found nothing. Not satisfied, the captain ordered a second search and a third — to no avail. That left just one possibility: Davis was in a world of danger. Somehow, he had fallen into the 15,000-foot-deep ocean. The captain contacted several nearby fishing boats, which helped search the surrounding waters. Still nothing. At 10:30 p.m., the captain reached for his marine radio and called authorities at the closest port in Peru.

No one answered. A chain of communications went out from the Victoria No. 168 to the ship’s manager in Panama, then to Davis’ boss in Alaska.

But it wasn’t until more than 24 hours later that the phone rang at the U.S. Coast Guard base in Alameda, California, to report the American missing. Every minute mattered. The water temperature where he vanished was 66 degrees, cold enough to be dangerous. A computer model estimated he could survive only a few hours longer.

With no vessels in the area, the Coast Guard contacted authorities in Peru. They couldn’t help. The ship was too far out to sea.

But on the tarmac in El Salvador, there was hope: a Coast Guard C-130 Hercules search-and-rescue plane. There was also a problem. The crew already had flown 45 hours that week, close to the 50-hour maximum. Reaching the ship, searching the area, and returning to land would require at least 10 more hours of flying.

From the ship came more troubling news: Davis’ life jacket had been found in his cabin. The odds of finding him were slim, if he was still alive. The plane stayed on the ground.

By late Friday, Sept. 11, time was running out. Davis had been missing for more than 30 hours. The Coast Guard tried a Hail Mary. It forwarded navigational coordinates to Davis’ cargo ship, directing it to the most promising areas to search.

By Sunday, ships had scoured more than 50,000 football fields of open ocean with no sign of Davis. But as the search ended, other activities were beginning. No longer was the Victoria No. 168, sailing under Panamanian authority, just another cargo ship. To U.S. authorities, it was a potential crime scene.

And that evening, they received a tip. “I have additional details that suggest his disappearance may be suspicious.”

In September 2015, fisheries observer Keith Davis vanished from the Victoria No. 168, a Panamanian-flagged cargo ship. His disappearance remains a mystery. MRAG Americas

Observers do the conservation dirty work along the supply chain that brings seafood to consumers around the world.

The data they gather, alone and far from shore, is the only independent information authorities have about how much and what kinds of fish are harvested from the world’s oceans and the collateral damage to marine mammals, seabirds, and other species.

This helps authorities set the rules for how much tuna and other fish can be taken out of the ocean each year. But observers do more than help take the guesswork out of fisheries management. They also scan the seas for illegal fishing, which is estimated to account for as much as 26 million tons a year, more than 15 percent of the global catch. Although observers are not authorized to stop illegal activity, their data is relayed to officials who can and sometimes do take action.

Many observers are young, often just out of college. They go to sea because they love the ocean and want to protect it. What they discover on vessels around the world is an environment not covered in marine science textbooks. There are hard drugs, loaded guns, knife fights, and ex-cons — a minefield of mayhem from which observers are not immune.

Some observers return from trips shaken and embittered, like veterans coming home from a war. Some never return at all. Since 2007, Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting found that at least nine observers have died on the job — four of them Americans. Foul play is suspected, but not proven, in at least two of the deaths.

Physical intimidation is only part of the problem. Some observers are offered bribes and fear reprisal if they don’t take them. If they are women, they may be targeted for sexual harassment or belittled as bad luck.

“It absolutely made me feel like a prisoner,” said Ellen Reynolds, an observer who spent two nightmarish months on a trawler in Alaska in 2008. The captain told her she was stupid, she said, read her emails, and ordered the crew not to speak to her. Someone stole her undergarments. She wanted out: “I couldn’t escape this boat. I couldn’t escape this person.”

On a different vessel in Alaska in 2011, observer Matthew Srsich noticed something odd: a half-gallon milk carton dangling on a line in front of him at eye level. Taped to one side was a powerful firecracker called a seal bomb. Boom! The blast knocked Srsich to his hands and knees. The ringing in his ears was nonstop. Unable to work, he battled headaches, earaches, and dizziness for the remaining two and a half weeks of the trip. Afterward, a doctor found he’d suffered significant hearing loss.

At the end of one workday somewhere off the Atlantic coast, Joe Flynn set his boots in the engine room to keep them dry. When he put them on the next morning, his foot got soaked. And his sock was yellow.

“The captain had pissed in my boot,” Flynn said.

Worldwide, there are an estimated 2,500 observers, about 900 of them American. Scores of companies compete for contracts to provide observers to government agencies and regional fisheries management organizations.

In the U.S., reports of observer abuse climbed from 28 in 2009 to 79 in 2015, according to National Marine Fisheries Service data. But many cases also remain in the shadows because observers fear they’ll lose their jobs if they speak out. Others don’t speak up because they believe nothing will be done.

Their plight is playing out as concern grows about the future of wild seafood and marine ecosystems. In many parts of the world, fishermen have caught too much, too fast, driving populations of bluefin tuna, Atlantic cod, and other species to alarmingly low levels. In the process, they’ve also netted, hooked, and killed vast numbers of sharks, seabirds, and marine mammals.

Never before have consumers demanded more accountability from the seafood industry. They want dolphin-safe tuna, turtle-safe shrimp, slavery-free prawns.

Yet the well-being of observers goes almost unnoticed.

“It’s as if they don’t exist,” said Elizabeth Mitchell, president of the Association of Professional Observers. “If people knew what observers have to go through to bring fish to their plate, they might feel differently about buying fish.”

Few observers spoke out more strongly for reform than Keith Davis. He was one of their leaders, a seagoing Cesar Chavez who fought for safer working conditions. He helped write an observer bill of rights calling for a workplace “free from assault, harassment, interference, or bribery.”

At 41, Davis was old for an observer. But with a boyish smile, chestnut-brown hair, and a seemingly inexhaustible reservoir of energy, he looked and acted years younger. Davis loved the wayfaring nature of the job, the long journeys at sea followed by downtime in exotic ports and at home in Arizona.

But observing had its downsides, too, as he pointed out in “Eyes on the Seas,” a collection of stories by observers that was published last year:

It can be tough simply being the odd-one-out on board. Scenarios of confrontation and harassment are bound to arise. … Though rare, I have even found myself in a few situations with no line of defense besides trying to remain calm, quietly documenting everything, and riding out a bad trip.”

It had all started when he was a young boy, fishing for flounder in Boston Harbor with his father and later, after the two moved to Arizona, snorkeling in Mexico’s Sea of Cortez. The ocean cast a spell. When Davis graduated from the University of Arizona in 1998 with a bachelor’s degree in ecology and evolutionary biology, he chose an emphasis in marine biology. The next year, he landed a job as an observer.

He worked on trawlers and crabbers in Alaska, scallop dredgers in New England, and long-liners in Hawaii. But in 2009, a new gig arose. In the high seas of the Pacific, pirate boats were off-loading illegal catches onto massive refrigerated cargo ships, laundering them as legal.

Davis, an experienced hand, was tapped to be one of the first observers on those cargo ships.

Out there, beyond the reach of authorities, was a Wild West–like frontier where boats chased glittering schools of tuna worth millions of dollars. Crewmembers were often as disposable as the bycatch.

While their bosses hungered for fortune, they were just plain hungry. Desperate for opportunity, they mostly came from poor towns and villages across Southeast Asia, sometimes tricked by unscrupulous recruiters. The captains push them hard. On some boats, they were beaten, denied medical care, and forced to work when they were sick. Some died. Others jumped overboard.

“Life is respected differently out there,” said Cheree Smith, a former observer in Oregon who knew Davis in Hawaii. “It’s open water and it’s a war, for money, for tuna.”

Keith Davis had logs from other observers detailing terrible working conditions aboard long-liners, including physical abuse. Keith Davis

Bubba Cook knew this insular world of observers well. A marine conservationist for the World Wildlife Fund, he was part of their tribe. He huddled with them at conferences, called them heroes of the sea.

As word of Davis’ disappearance spread, Cook sat in his office in coastal Wellington, New Zealand, distraught. Davis was one of his friends.

He looked down at his laptop and tapped at the keyboard, composing a message to the International Labor Organization, which oversees working conditions for mariners. Outside, it was dark and wet. Most people had gone home for the evening. Gradually, the tapping intensified and a drumbeat of words spilled across the screen.

Keith was a positive, upbeat guy. He was not depressed. He was far from suicidal. He was also an experienced and able-bodied seaman. He would not just “slip over the side” or otherwise put himself in any situation that might compromise his safety or welfare.

I can’t state this publicly because his family is still understandably coming to grips with the possibility that he will not be found. But myself and other fisheries observers know in our guts what has happened so I will say explicitly what so many of us are thinking:

Keith was murdered.

As a fisheries observer aboard the Victoria No. 168 cargo ship, Keith Davis carried no badge or weapon. He had no way of signaling for help without going through a computer in the captain’s quarters. Ike Sriskandarajah/Reveal

Ten days after Keith Davis vanished, a small army of investigators gathered to board the vessel north of Panama City. Because Davis had gone missing in international waters from a ship registered and flagged in Panama, that nation was in charge of the investigation.

Authorities from the FBI and Coast Guard were there, too. And with them was a civilian whose business was partly personal.

With a bushy, brown mutton-chop beard, Bryan Belay was not someone who blended into the crowd that day. He looked like a mariner from another century.

Belay was Davis’ boss at MRAG Americas, which hires observers for deployments around the world. Davis was one of his most reliable hands — outgoing, experienced, a student of the sea, and committed to protecting it.

Davis’ loss gnawed at him. At times, he could feel sorrow welling up. He kept it in check; there would be time to uncork those emotions later. He had a job to do: help U.S. authorities with the investigation.

Soon after boarding the ship, he noticed something. It was spanking clean. Even the safety posters looked new. There also were two freshly painted spots on the deck. Routine maintenance, someone told him.

One thing was clear: The Victoria No. 168 had been at sea 10 days since Davis disappeared. It’s a period of time you can’t account for anything, Belay thought. That is a huge problem for the investigation.

The ship’s galley was transformed into a command center. In the front of the ship, investigators were interviewing the officers and crew. Belay was not privy to the conversations. But now and then, investigators popped into the galley to ask him questions. “Is this the way you would expect it to be?”

They did not single out a suspect. But one man was interviewed at least twice, Belay recalled.

There was added intrigue in Davis’ cabin, where investigators found a cache of belongings that told them more about him. A mandolin and four sets of headphones — the man loved music. A survival suit — he was serious about safety. A well-thumbed diary and books about nature, religion, and self-fulfillment — he loved the outdoors, but was a pilgrim of the inner world. A tool kit, sewing kit, flashlight, and compass — he was ready for anything, a MacGyver kind of guy.

Most important were two silver laptops. The U.S. team copied the drives. On them, they found notes and photographs documenting the dramatic last three weeks of Davis’ life on the cargo ship. But that was just the start. There were files reaching back years that opened a window onto the hidden horrors Davis and other observers encountered at sea: the bedbugs, cockroaches, lousy food, and malnutrition. The desperate crewmembers, random violence, and 24/7 tension.

There was a vault of interviews with observers talking candidly about their lives at sea. “It’s a dangerous profession,” one observer said in one of the recorded interviews. “You put your life on the line. You could lose your life on the line.”

In a separate folder, he stored logs from other observers, detailing scenes of violence, death, and despair that normally are kept confidential.

March 24, 2012 — The captain of [a cargo ship] asked my permission to transfer a deceased Philipino [sic] crewman from [a long-liner]. … Upon talking to another Filipino crewman … I learned that his friend (deceased) had been sick for over two months and the captain did nothing to get him proper medical attention or provide any additional meals besides the rice allotted one time a day.

March 26, 2012 — The captain … beat an Indonesian crewman, reportedly for being too sick to work. … As an observer, I’m uncertain as to what I should do. … Standing by and simply writing a report in my daily log about human rights violations seems pretty insignificant and is very difficult for me to do.

April 2, 2013 — They are worked hard, up to 20 hours a day, fed mostly baitfish and rice and are abused physically and verbally. … On my last voyage I was told that one … captain was stabbed by a crewman and because an artery was cut and would not stop bleeding, the ship had to run for days to Tahiti so the captain could get medical attention. Some of these crewmen are at sea for two years before they see land again and under the conditions they have to work and live in to survive, they lose it. I was told by the Vietnamese crewmen that they were not allowed food if they did not work, even though they had been injured and were not physically able to work. I think that it is important to document these things in the hopes that someone will realize how bad things can be for those that are imprisoned at sea and have no voice.

Ten weeks earlier, Keith Davis had been back in the White Mountains of Arizona, manning the barbecue for his dad’s 70th birthday. Davis had gone all out, inviting friends and neighbors and filling up plate after plate with ribs, burgers, and chicken. Later, he picked up his guitar and sang a Neil Young classic. Old man, take a look at my life, I’m a lot like you.

Now the house was quiet. John Davis stared out at the gin-scented junipers and powder-blue sky. Keith was his only son. He’d raised him as a single parent since he was 10. The hurt was nonstop.

Keith Davis and his father, John, shown in Arizona’s White Mountains, traveled around the globe together. “Me and him talked about everything. We were best buds,” John Davis said. Courtesy of John Davis

“The relationship my son and I had is one you dream about: traveling all over the world, diving together, seeing stuff,” he later would say. “Me and him talked about everything. We were best buds.”

John walked into the living room and sank into the couch. On the wall were photos highlighting their years of globetrotting. Memories washed over him: scuba diving in Thailand, a jungle trek in Sumatra, a safari in the Serengeti. At the party, Keith had given him two bottles of champagne. They opened one. He put the other in the fridge. He’d drink that one when his son came home.

John was helping Keith build a home a short walk away through the junipers, a place to land when he left the sea. John long wondered when that day would come — if it would. The ocean was Keith’s recharge zone, a sanctuary where he found solace and inspiration. The money wasn’t bad, either. On what turned out to be his final voyage, he was earning about $1,600 a week.

A few days after Keith disappeared, John spoke by phone with Matthew Margelot, resident agent in charge with the Coast Guard in California. They talked about a tip that had landed in an FBI inbox.

Keith’s former fiancée, Carla Hilts, warned that Keith’s disappearance might be suspicious, directing the FBI to an incident at a conference in Chile in 2013. John had been there and the memory came flooding back: a crowded room, a panel of speakers, his son at a microphone speaking out about safety, saying not enough had been done to protect him and other observers.

Afterward, Keith recounted how someone had sidled up to him with a warning: “You don’t know who you’re dealing with.”

John could tell his son was rattled. “We ought to stick together,” Keith told him that evening. “These guys are very powerful.”

Worried about his safety, Keith Davis did something after the conference that surprised his father: He retired from observing. He’d had enough. It was time to move on. He yearned for a job on land, a wife, a family.

Keith Davis, shown with onetime girlfriend Anik Clemens, was an outspoken advocate for fisheries observers. He helped write an observer bill of rights calling for a workplace “free from assault, harassment, interference or bribery.” Courtesy of Anik Clemens

And by the next year, he’d found the right woman: Anik Clemens, a single mother and former observer from Florida he’d met years earlier in Hawaii. Clemens was looking for someone, too. Maybe it could work. She invited him out for a trial run. Driving cross-country in a rundown Nissan pickup, Davis swept into her life like a gust of wind.

“Keith was a character,” she recalled. “He was all at once charming, opinionated, intelligent, carefree, and yet there was a mystery about him. When he laughed, there was a twinkle in his eye, as if he knew a secret only he could share.”

Davis warmed to Clemens’ 3-year-old daughter as though she were his own. They went paddleboarding, palled around at a playground. One day, he taught her how to hug a tree. After dinner, he played his guitar and sang the little girl to sleep. Her favorite song: “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” the ethereal version by Hawaiian singer Israel Kamakawiwoʻole.

One day, Davis told Clemens, “I love you.”

She hesitated. She knew the sea still tugged at him. He was wedded to it. The relationship wasn’t going to work. They separated, warmly.

A few days later, she checked her inbox. There was a message from Davis. He was on his way to Tahiti. He was going back to work as an observer.

A year later, the tragedy preyed on her, robbed her of sleep. How can a person go missing in 2015 and there is no evidence of what happened? Night after night, she stayed up late, playing detective, reading Facebook posts and emails, sifting through her memories. Was there something she had missed? She had always loved puzzles. Now she was living in one.

Sitting by the pool of her condo, she picked up her iPhone and called Margelot, the Coast Guard investigator. She told him something interesting: Davis had written a song about observers who died at sea. He even recorded himself singing it — on a cargo ship, no less. It had some chilling lines:

Some say he’s lost. Maybe he’s been found.

If you listen on the breeze, still hear his sound.

Must have been his time to go. Something we’re not meant to know.

He’s left us his legacy. Now he’s all too free.

Some suicide victims leave notes. Did Davis leave a song? She didn’t think so. It was much more likely, she believed, that someone killed him. A month later, Clemens emailed Margelot and told him just that:

I have been thinking about Keith every day and am wondering how the investigation is going. … The image that keeps coming to my mind is that Keith saw something he wasn’t supposed to see and Keith’s head was bashed into something … and there was blood everywhere and then he was thrown overboard.

Standing at the rail, Davis stared out across an angry sea on Aug. 18, 2015. The wind howled and moaned, stirring up cobalt blue swells that galloped from horizon to horizon. Out there in the froth, a long-liner was approaching.

As the boat drew close, Davis reached for his Fujifilm point-and-shoot and pressed the shutter. Ringed with green scum, badly in need of a paint job, the Chung Kuo No. 39 was anything but pretty. The crew looked scruffy, too. Some wore full-face stocking caps, the kind bank robbers wear.

Like hunters on the Western frontier, long-liners roam the sea for years, never going to town. What keeps them alive are cargo vessels — sometimes called mother ships — that deliver food, fuel, and other supplies while also ferrying their frozen fish back to shore. The Victoria No. 168 — owned by a Panamanian company, Gran Victoria International — was the mother ship for the Chung Kuo No. 39 and a fleet of other long-liners. They were owned by a Taiwanese company, Gilontas Ocean Group.

After the two ships were tethered together with thick ropes, Davis watched in awe as a crane on the cargo ship began to hoist bundle after bundle of frozen silver-gray fish out of the long-liner. He’d seen it before, but it was always impressive, especially on stormy days. Swinging through the air, bigger than German shepherds, some bigger than calves, were fish that would feed thousands, that would be spread on sandwiches, sliced into sashimi, and plopped into steaming pots of soup.

On the Chung Kuo No. 39, a long-line fishing vessel, a man appears startled or angry as he points his finger at Keith Davis. In the boat’s net are albacore being transferred to the cargo ship. Keith Davis

More than 10 hours later, nearly 60 tons of albacore, bigeye tuna, shark, and other fish had been loaded. Most of Davis’ photos from that day are routine. But one sticks out. On the Chung Kuo No. 39, a man is pointing his finger at Davis. He looks startled and angry.

Over the next week, more Gilontas long-liners pulled alongside. All were authorized to fish in the eastern Pacific by the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission. Still, Davis grew frustrated. The fish were so heavily butchered that he struggled to identify them. There were tuna with no heads, billfish with no bills, sharks with no fins. It was a slaughterhouse. He wondered whether the long-liners were trying to disguise bluefin tuna as bigeye to get more of them to market.

Other observers might have done nothing. Not Davis. From the computer in the captain’s quarters, he emailed a U.S. government fisheries biologist in Hawaii, Joe Arceneaux:

Tuna on this ship are coming up not gilled and gutted, but dressed [heads off]. How can you tell the difference between a big Bigeye and a Bluefin with no fins and head? … Mistaking Great White Sharks and Bluefins could cause some serious management issues.

One afternoon, something suspicious happened. “The only bluefin I have seen out here (I have a photo) they started to transport over, until I started to take a photo of it — when they brought it back to their ship rather hurriedly,” he wrote to Arceneaux.

Fish being loaded onto the cargo ship were so heavily carved up that Keith Davis struggled to identify them. He wondered whether fishermen might be trying to disguise one kind of fish as another. Keith Davis

Bluefins are the most valuable and imperiled of tuna species and subject to catch limits. In the Pacific, their population has plunged below 3 percent of its historic unfished level. They are also enormously valuable. A single bluefin can sell for tens of thousands of dollars and up.

Davis shouted over the rail, asked what they were doing. They told him they’d caught it in the Indian Ocean, outside the commission’s jurisdiction. Davis was skeptical. He had no way of independently contacting anyone about it. Again, he emailed Arceneaux.

Mariners on both vessels also were tossing garbage overboard. Davis couldn’t let that go, either. It was a violation of an international convention forbidding the dumping of waste at sea. As water bottles, plastic bags, and who knows what else plopped into the water, Davis took photos and shot video, logging more than a dozen potential infractions.

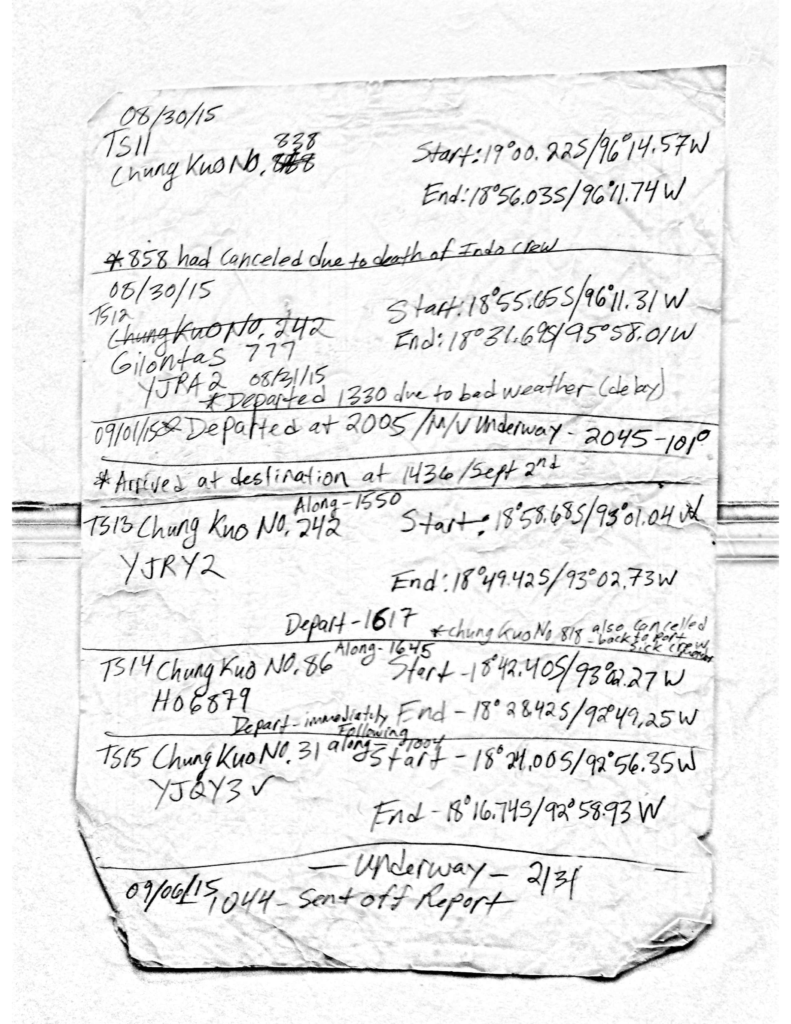

In handwritten notes, Keith Davis recorded that an Indonesian crewmember on a long-liner had died, but didn’t mention the cause. A few days later, he noted that a long-line crewmember on another vessel was seriously ill. Keith Davis

Late August brought leaden skies, gauzy sheets of rain, more swells and a psychological jolt. From the ship’s chief officer, Davis learned that an Indonesian crewmember on a long-liner had died. Davis noted the death in his log but didn’t mention the cause. A few days later, he heard that another long-line crew member became so ill that the ship’s captain steamed to Lima, Peru, for medical help, some 500 miles away.

That vessel, the Chung Kuo No. 818, returned to off-load its catch Sept. 10. The work began at 8:35 a.m. under a blanket of clouds. The winds were light, the waves two to three meters. When the work was over that afternoon, Davis returned to his cabin near the rear of the ship. About 4, the chief officer walked to Davis’ door to ask him to sign some paperwork.

There was no one inside.

Before boarding the Victoria No. 168, Keith Davis spoke by phone with his boss, Bryan Belay, who briefed him about a potentially dangerous situation on the vessel.

“I do remember specifically telling him that previous observers had had issues with the crew and to be aware of that and that it could be a tense situation on that vessel,” Belay said.

But he added: “I had no indication there was a threat to the observer safety, or else I would not have placed an observer on that boat.”

Michael Gauthier, the previous observer on the vessel, had seen it with his own eyes. Hierarchy and discipline had broken down on the ship.

“My impression was this crew really didn’t like each other. More so than any other crew I’ve ever seen before,” he said. “There were these two big factions broke up by nationality and language. Even more than that, there were subcliques within those cliques, and no one seemed to like each other.”

Gauthier finished his voyage without incident. But he was careful.

“It’s wise to play things close to the chest,” he recalled. He had a fallback plan. If someone got too curious about what he was doing, he’d play dumb. If someone asked why he’d taken a photo, he’d say: “Oh, it’s nothing. It’s an interesting fish. I want to take a picture of it.”

Davis wasn’t as likely to play dumb. He was more direct than most observers, at times confrontational.

“He was an outspoken steward of the sea, in-your-face kind of guy when it came to what he did and stood for,” said Caleb McMahan, a former observer in Hawaii and friend of Davis.

A year before, he’d gotten into a brawl at an observer party in Hawaii. Anik Clemens saw him the next day: There were bruises on his neck and chest and a gash on his foot. “When I first heard about him being missing, I thought: ‘Shit! What happened now? Did he get into a fight?’” she said.

Davis’ loss stunned Gauthier. He had no idea what happened. But he was sure of one thing: If Davis was killed, it was not a shipwide conspiracy.

“That is absolutely inconceivable,” he said. “These people could not conspire to successfully complete a workday. There’s no way they could conspire to murder somebody and keep that secret. Someone would have talked by now.”

Like hunters on the Western frontier, long-liners like these may roam the sea hauling in fish for years, never going to town. Keith Davis

Neither Panamanian nor U.S. investigators have disclosed details or documents about their investigations. But in hindsight, one official says the search was flawed because it happened much too late.

“In ordinary criminal investigations, we talk about the golden hour, the first hour after a crime,” when evidence is fresh, said Michael Berkow, director of the Coast Guard Investigative Service. “Here, we had to wait until they came in to their next port of call. There are some very real and unique challenges posed by the tyranny of time and distance on these kinds of cases.”

For U.S. investigators, there was another obstacle: jurisdiction. Under maritime law, Panama was in charge because the Victoria No. 168 flew its flag. The ship was sovereign Panamanian territory. The U.S. was there by invitation only. And just days into the investigation, Panama did something dramatic.

“They asked us to step away,” Berkow said. “We honored that. We don’t have a choice. They are the ones that control this.”

The Coast Guard suspended its investigation. There was nothing to do but wait for the Panamanians. The agency is still waiting.

“Normally, when the Panamanian prosecutors close a case, they generate a final document,” Berkow said. “We certainly have not seen it.”

Frustrated, Keith Davis’ family and friends have demanded more answers from the FBI. In August, his friend Elizabeth Mitchell, the observers association president, emailed the FBI with a question about Panama’s probe.

“We were informed on May 31 by the Panamanian prosecutor that the matter was being sent to their courts with a recommendation that the case be closed,” FBI assistant legal attaché Isaac DeLong responded. “There were no new investigative leads. … I know this still leaves a lot of questions unanswered. … Unfortunately some of those questions may remain unanswered.”

For Davis’ father, John, that wasn’t good enough. In October, he emailed the U.S. Embassy in Panama asking for a copy of Panama’s investigation. He received unwelcome news.

“The Panamanians did not do a final investigative report,” wrote consular officer Stephanie Espinal. “According to the FBI … there was never any final comprehensive report as would likely have [been] done in the United States.”

None of the men on the Victoria No. 168 when Davis disappeared remain with the vessel, said Belay, Davis’ boss. They’ve gone home or are working on other boats.

Five of the mariners were living in Myanmar as of last fall. All five declined to be interviewed for this story. Efforts to reach the rest of the crew yielded little. One crewmember responded to an email, but said he didn’t know what happened to Davis and asked to be anonymous.

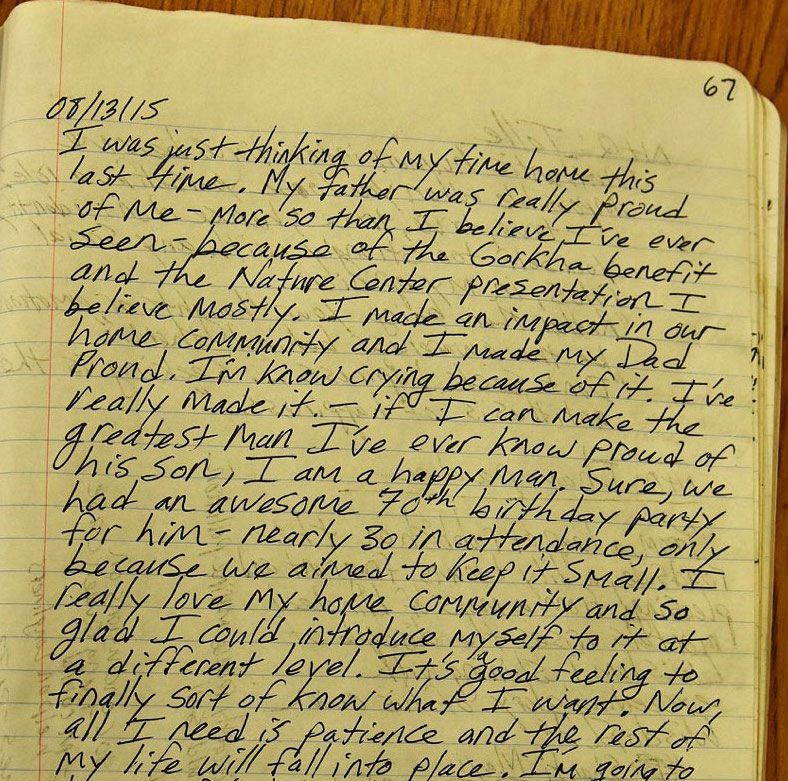

Keith Davis’ Aug. 13, 2015, journal entry reflects on his life and his father: “I’ve really made it – if I can make the greatest man I’ve ever (known) proud of his son, I am a happy man.” Courtesy of John Davis

Nearly everyone who knew Davis believes he was killed. But no one has any evidence. There’s no clear motive. There’s no suspect. There is only a mystery.

“What happens at sea stays at sea,” said Henrique Ramos, a former observer in the Azores. “How can you prove that something happened? You just can’t.”

If the government investigations have turned up anything, they’re not being shared, even with Davis’ family.

Foul play, of course, is not the only possibility. Davis, who had experienced chest pain on a previous trip, might have lost consciousness and fallen overboard. That would be unlikely on the main deck, where the rail is metal and more than three feet high. But outside Davis’ cabin one floor above the main deck, the rail was not metal, but rope.

Perhaps something personal pulled him over the edge? Something we’re not meant to know, as he wrote in his song. If so, he hid it well.

“The boy loved life,” his father said.

Davis’ journal entries from the ship seem to back that up. He wrote on Aug. 13, 2015:

I was just thinking of my time home. … My father was really proud of me — more so than I believe I’ve ever seen. … I’m [now] crying because of it. I’ve really made it — if I can make the greatest man I’ve ever [known] proud of his son, I am a happy man.

We had an awesome 70th birthday party for him. … I really love my home community. … It’s [a] good feeling to finally sort of know what I want.

One thing is certain: His death was a wake-up call. All observers for Davis’ former company now carry two-way satellite texting devices, allowing them to reach the company without going through a ship’s computer.

“It is something we felt strongly about after this incident,” Belay said. “We needed to get something to ensure we had independent communication.”

Plenty of other observers who don’t work for MRAG continue to have only one way of communicating problems to shore: through the communication system of the ship they’re observing.

Last year, the accounting firm Moss Adams LLP suggested a stronger response: halt the high-seas long-line observer program altogether and ban the Victoria No. 168 from the global fishing industry.

“The loss of an observer … brings into question whether this program should be allowed to continue,” the company said in a performance review of the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission.

The oldest of five regional tuna management organizations, the commission is composed of more than 20 countries and is responsible for the conservation of tuna and marine mammals across 26 million square miles of the eastern Pacific, about 20 percent of the world’s oceans. It is based in San Diego.

“Any vessel involved in an incidence of the loss of life of an observer should never be allowed to operate again in any global fishery,” Moss Adams said in the report.

The tuna commission appears less troubled. In June, it posted a report about its high-seas observer program. It included not one word about Davis.

“The program is operating without any major problems with regards to its implementation and management,” it said.

That shocked many people, including Joe Arceneaux, the federal fisheries biologist whom Davis emailed from the Victoria No. 168.

“One of your guys disappears under strange circumstances, and you act like there’s no problem?” he said. “That’s a problem. Somebody should own it. And nobody wants to.”

Guillermo Compeán, director of the commission, said responsibility for observers in the transshipment fleet rests with the company that employs them.

“We are not involved with the management of the observers,” he said. “It is an outsourcing contract with MRAG.”

He also said cracking down on human rights abuse is not the commission’s responsibility, either. “Our observers are not officials of the law,” he said.

Last year, a British human and environmental rights group, Global Witness, posted a report calling attention to a record 185 environmental advocates killed in 2015 struggling to protect rainforests, wildlife, and other resources. Most were from South America and the Philippines. But one was American: Davis.

“The environment is emerging as a new battleground,” the report said. “The numbers are shocking. … On average, more than three people were killed every week in 2015.”

A generation ago, many U.S. observers were federal employees. But to save money, government officials farmed out the jobs to contractors, the Halliburtons of fisheries management. Some say that should change.

“They need to be federal employees because of the high-risk nature of the job. The contracting system does not offer them adequate protection,” said Teresa Turk, a former fisheries biologist with the National Marine Fisheries Service. “They are just so incredibly vulnerable.”

Today, the Victoria No. 168 continues to rendezvous with tuna long-liners in the Pacific. “There is another observer on the boat. There’s no justice for Keith in all of this,” said Caleb McMahan, his friend in Hawaii.

John Davis during a memorial for Keith Davis at a San Diego observer conference in 2016, flanked by Reuben Beazley, left, a veteran observer, and Dennis Hansford, right, of the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service. Tom Knudson/Reveal

Last August, a small group of people huddled, heads bowed, near the beach of a San Diego resort. They’d come from around the world for an observer conference. As white flowers were tossed into the platinum bay, as music written and performed by Keith Davis floated through the air, they were saying goodbye.

No one took the loss harder than the 71-year-old man who stood before the group wearing a New England Patriots cap and holding a can of Saint Archer blonde ale: Davis’ father, John. He had traveled hundreds of miles from Arizona to be there. Two friends stood at each shoulder, as if sheltering him from a heavy gale. Fighting back tears, he struggled for words.

“Let’s get it done,” he said. “Let’s make observers out there safe.”

Editor’s note: Scenes and details in this story have been re-created through meticulous sourcing, including dozens of interviews, emails from key players, government documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, and information found on Keith Davis’ hard drives, including photos from his final days on the Victoria No. 168 and his journal and logbook entries.