For more than 60 years, one section of Enbridge’s elaborate network of pipelines carrying petroleum across Canada has taken a detour through the Bad River Reservation in northern Wisconsin.

Some of the easements that allowed Enbridge to keep its Line 5 pipeline on the tribe’s land expired in 2013, and negotiations between Enbridge and the tribe to renew the leases fell through. Yet Line 5 is still funneling Enbridge’s petroleum across the Bad River Reservation. The tribe says Enbridge is trespassing, and has sued the company to kick it off their property.

If a bill awaiting Wisconsin’s Democrat Governor Tony Evers’ signature becomes law, members of the tribe protesting Enbridge’s operations on their reservation could face fines of $10,000 and up to six years in jail.

“It provides these illegally operating companies with the right to basically charge someone with a felony for being on their land,” said Philomena Kebec, a citizen of Bad River and former tribal prosecutor. “And this could be an Indian person on Indian land where the company is illegally trespassing.”

The Wisconsin bill is part of a wave of similar legislation raising penalties for trespassing or damaging oil and gas infrastructure around the country. Support for bills penalizing protestors followed in the wake of the Dakota Access Pipeline protests in North Dakota nearly three years ago. So far, at least eight states have such laws on the books, according to the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, a watchdog group tracking the legislation, and several others — including Wisconsin, Ohio, and Pennsylvania — are considering similar proposals.

Under a 2015 Wisconsin law, trespassing and damaging property owned, operated, or leased by an “energy provider” — mainly electric and gas companies — is a felony. The new bill expands the definition to include companies with petroleum, chemical, and “renewable fuel” infrastructure, a change that would protect the many pipelines that crisscross the state. It has the backing of oil and gas groups, labor unions, and a renewable energy developer, EDP Renewables.

Last month, 36 environmental and free speech advocacy organizations sent a letter warning Wisconsin state senators that the measure would create a “chilling effect on those citizens who want to exercise their First Amendment rights” and have “drastic impacts on people of color.” Still, the Senate passed the bill last week.

The Bad River Reservation, an approximately 125,000-acre tract on the south shore of Lake Superior, was established in 1854 by a treaty with the federal government. Although the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians is sovereign, state criminal laws apply within the reservation as a result of a federal law called “Public Law 280,” which grants several states — including Wisconsin — law enforcement authority within tribal nations. As a result, if Governor Evers signs the new bill, it would apply to Native Americans on tribal land.

Kebec worries that it would put more Native Americans in jail. In Ashland County, where part of the Bad River Reservation is located, 44 percent of the inmates in the county jail are Native American, even though they make up just 11 percent of the population.

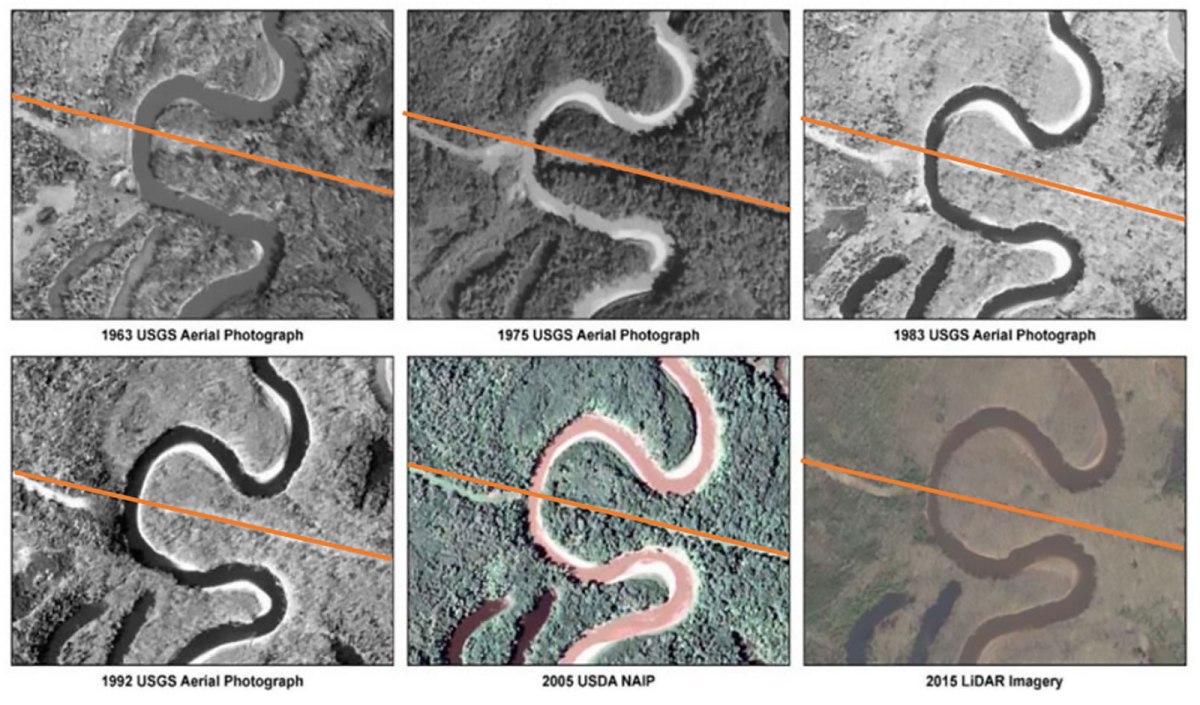

Members of the Bad River Band are particularly worried about Enbridge’s operations within the reservation because the Bad River’s path meanders, eroding sediment off the riverbanks. In 1963, ten years after Line 5 was installed, the river bank was 320 feet from the pipeline. By 2015, the distance had shrunk to 80 feet. Now, the distance between the two is 28 feet.

Aerial images of a meander in the Bad River show erosion of the river bank over time. The distance between the river and Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline is now just 28 feet.

At this rate of erosion, according to the tribe’s legal filings, the river will expose the pipeline within two to five years. If that happens, it would “represent an existential threat to the Band, its Reservation resources, and its way of life,” the tribe’s lawyers argue. A spill could spread into the Kakagon-Bad River sloughs and Lake Superior, contaminating the watershed and preventing the tribe from fishing and harvesting in the area.

The lawyers for the tribe say Enbridge should have removed the pipeline and restored the land soon after the leases allowing the pipeline on the land expired in 2013.

Juli Kellner, a spokesperson for Enbridge, said the company “has attempted to find an amicable solution” and that it now “finds itself in a lawsuit that will hopefully resolve these issues.” Enbridge holds different types of agreements giving it access within the reservation, including with private landowners and through the Bureau of Indian Affairs. She said these other arrangements require the tribe “to do everything it can to effectuate a full easement for Line 5 through the reservation.”

At a press conference last month to oppose the bill, Bad River Tribal Chairman Mike Wiggins Jr. said that Native Americans often lack “any mechanisms to try to stand up for our land and water” and that protests were one way for Native Americans to advocate for their rights. “There’s a fear rooted in this bill of peaceful, non-violent protesters,” Wiggins said.

Land ownership on the reservation can be complicated. Tribe members who were allotted private land within the reservation by the federal government passed on the allotments to their children when they died. Over generations, small plots of property eventually ended up with dozens — sometimes hundreds — of co-owners, said Kebec, the former prosecutor. As a result, Native Americans out berry-picking or hunting may have trouble proving lawful entry on reservation land. “I’m very much concerned about tribal members who are out on our reservation, just exercising our regular treaty rights,” she said.

In an effort to address situations when people may unknowingly enter private property where pipelines and other structures are buried, a group of lawmakers attempted to add language about trespassers’ “intent” to the bill. The amendment would have made it a felony to trespass “with the intent to present a substantial threat of bodily harm to one or more persons.” But the effort failed, and the bill passed without that language.

Kellner, the Enbridge spokesperson, said the company “respects the rights of others to express their views on the energy we all use,” but that “trespassing and occupation of pipeline facilities have the potential to cause serious harm.”

“We don’t tolerate trespassing, vandalism, or mischief, and Enbridge will seek to prosecute those individuals to the fullest extent of the law,” she said.