One of my favorite movies, as devastating as it is to watch, is Alfonso Cuarón’s 2006 dystopian thriller Children of Men. In it, an unexplained infertility pandemic threatens the survival of humankind. The youngest living person is 18. And in a world without children, without their laughter and their hope, humankind has gone kind of batshit.

Part of what draws me to this movie is its chosen narrative of what could lead the world to apocalypse. I don’t have kids, and don’t know if I ever will — but I get it. If there were no future generations to pass the world on to, what would be the point of working to make the world a better place?

Lately I’ve been considering another take on this story. What if, instead of the children, we started to see the world itself disappear? Future generations keep coming, but we begin to lose the air, the water, the soil that should have sustained them for years to come? How would we live our lives then?

Unfortunately, this isn’t a thought experiment starring a darkly clad Clive Owen. It’s real life. And that reality has some emotional consequences for all of us living on the planet today — perhaps none more so than the parents whose children will inherit the worst impacts of the climate crisis.

Mustafa Önder

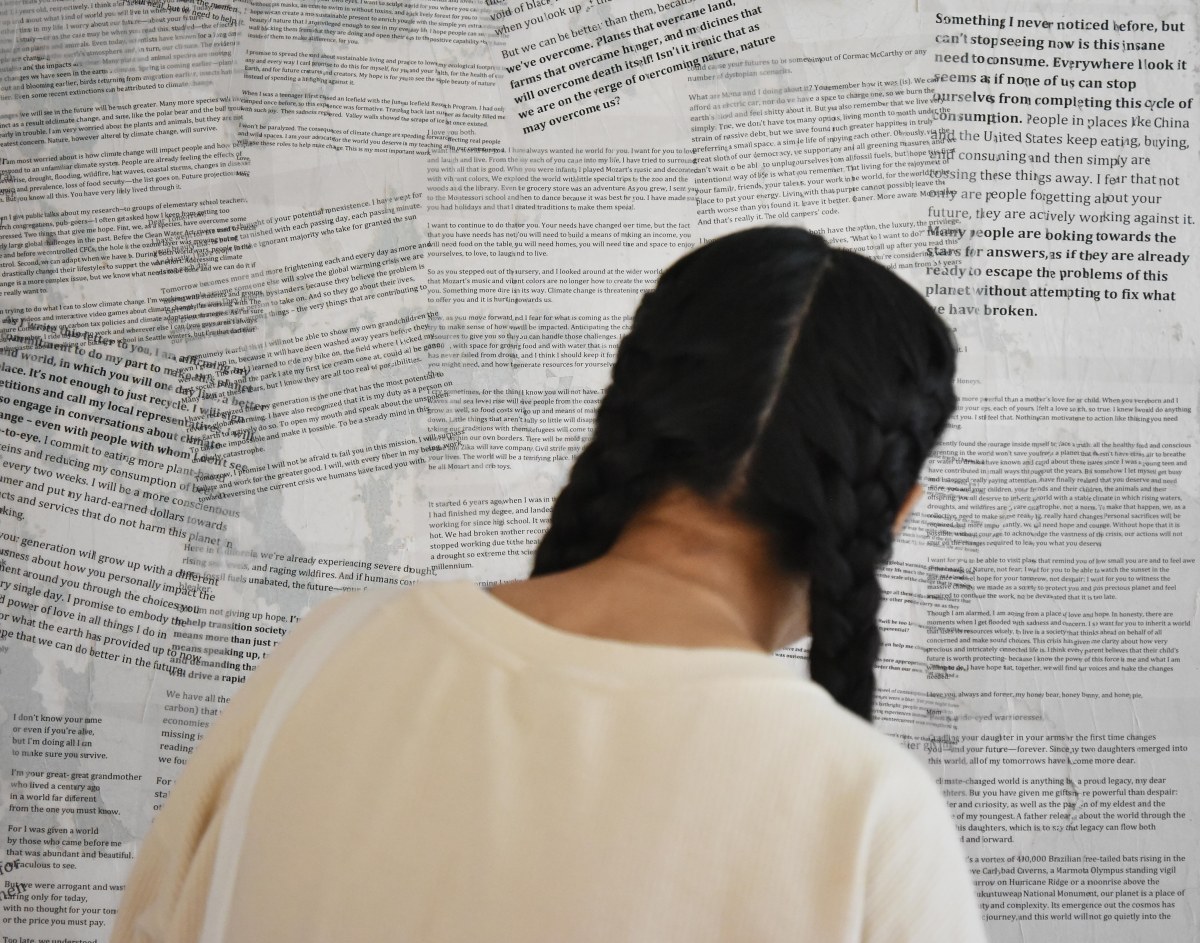

I was thinking about this on a recent trip to New York City. In the midst of Climate Week, I had a chance to visit Governor’s Island — a 172-acre city escape boasting bike paths, a hammock grove, and stunning views of the Statue of Liberty. It’s a fitting location for an installation titled “DearTomorrow: A Promise to the Future.”

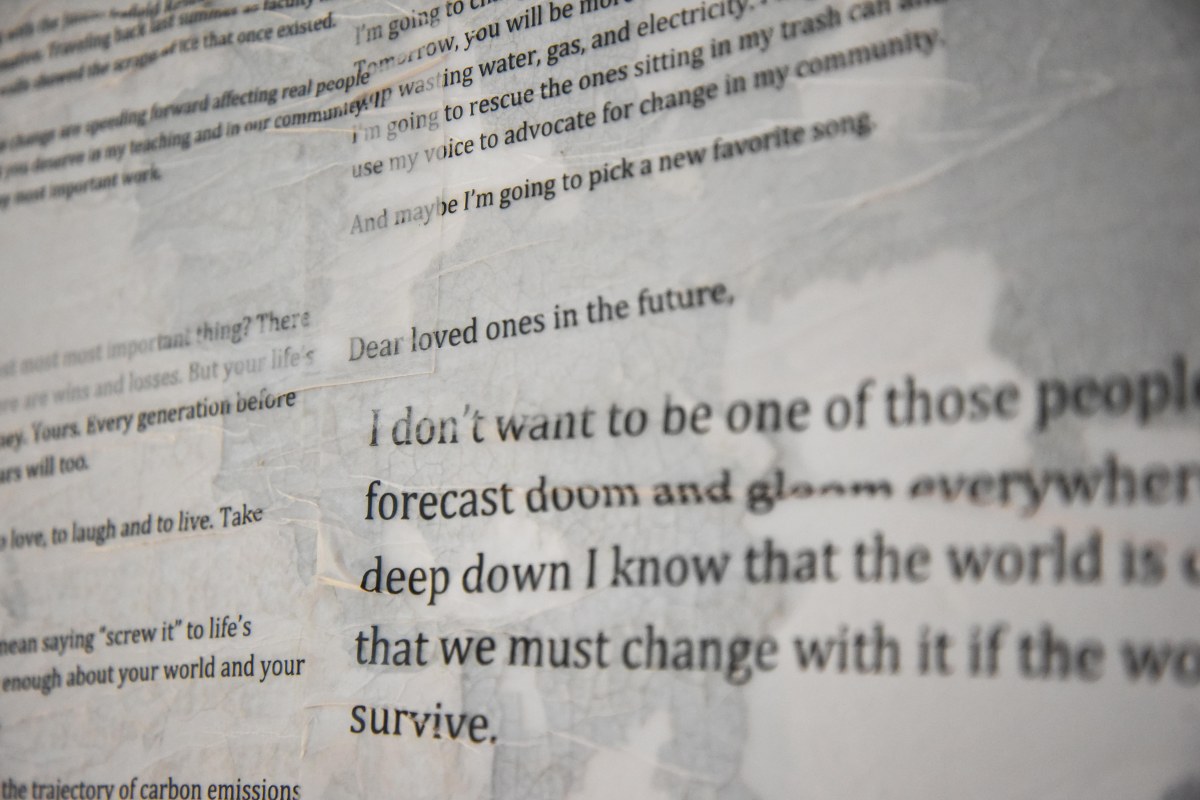

The installation, which closed October 27, was located in a room on the second floor of the House of Solutions. The room was wallpapered with 50 letters to the next generation, in which people described the way the world is now and the things they hope and fear for the future. Many of the writers also made promises to that future — often to their own children.

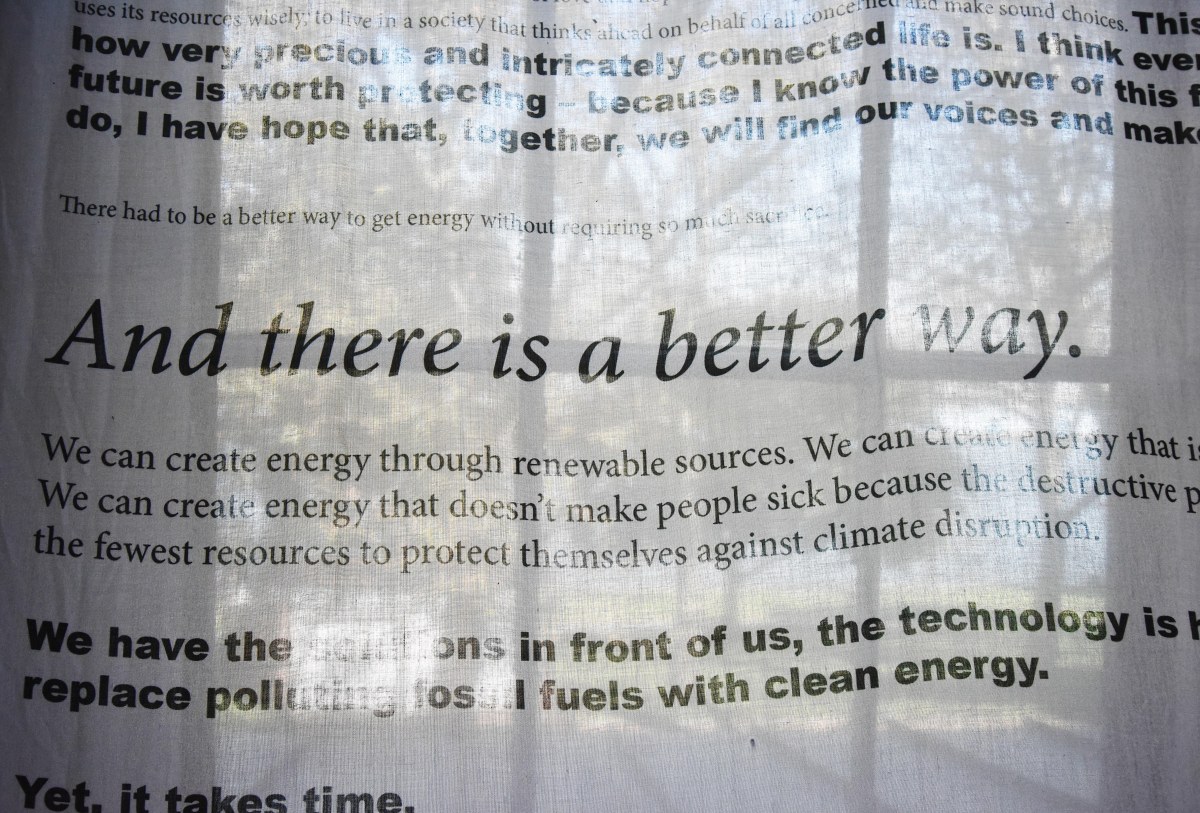

A long piece of fabric, draped over the window and the floor like a gown, held choice quotes from some of the letters, and four speakers brought the voices of the letter-writers into the room.

“We knew what was happening to the glaciers. They were disappearing.”

“I’m working smart for you. Many of us are.”

“How can I look at your bright eyes … and tell you we are facing a war?”

The exhibit was the work of Jill Kubit, an organizer and nonprofit leader, in collaboration with visual artist Tara DePorte and sound architect Lemon Guo. It was the first live, audio-visual installment of DearTomorrow — a letter-writing and climate advocacy project founded by Kubit and Trisha Shrum, two alums of the Grist 50.

Kubit said that, after a decade of climate activism and academia, her work really became personal for her when she became a mother. Inspired by a letter Shrum had written to her baby daughter, to open in 50 years, Kubit decided to go through the same exercise.

“We [in the climate movement] use these future references like 2020, 2030, and 2050,” Kubit said. “When I sat down to write a letter to my own child, I imagined his life in those milestones — and I felt like I could actually see those times happening so quickly, and that he wasn’t actually going to be that old in the year 2050. He would be about the age that I was when I was writing to him.”

The two encouraged others to write letters, too, and the project took on a life of its own. The DearTomorrow website is now home to more than 1,500 letters and photos from people all over the world. Kubit and Shrum have each contributed their own loving messages to their children: “I commit to being part of the climate movement. I will think and talk about climate change and the legacy that I am leaving for you. I will listen to you because I know you will have amazing ideas to add, a new way of looking at this changing world.”

Mustafa Önder

We don’t know what the world is going to look like in 2050. DearTomorrow letters give us an opportunity to dream into that future — which can be both empowering and scary. Some of the letters express fear, and grief, and apologies for not doing more to ensure a livable world for the next generation. Others are promises to start doing just that.

Shrum, an economist and behavioral scientist, points out that the massive threat of climate change can make a person feel “really weak and small.” Any actions you can take as an individual are just a drop in the bucket, and that stops some people from taking action at all. But, when you’re standing in between your child and climate catastrophe, it’s a bit of a different story.

“When you’re talking to your kid, and telling them about what you did and how you acted and how you worked to create a future that they would want … every excuse you can possibly make falls flat,” Shrum said. “You’re the most powerful person in the world for your kid. And it’s your job as a parent to protect them.”

In her work as a behavioral scientist, Shrum has found that a DearTomorrow-esque letter-writing exercise can increase a person’s motivations to act, or support others’ actions, in the present. This is especially potent for parents and grandparents, Shrum said. “When you write to your own child and you can imagine your own child living in the future, you mentally create a pathway towards a hopeful future.”

Shrum has found that parents and grandparents are willing to donate more to particular causes than other folks — even aunts and uncles — after going through the exercise. She thinks this is because parents are already used to sacrificing for their children, “whether it’s, you know, the exorbitant amounts we pay for childcare, or giving up your social life, or all of the things that we do, we’re already willing to pay a lot more to help our own kids than we are for the generic children of the future.”

Shrum and Kubit are careful not to prescribe any particular actions or lifestyle changes to DearTomorrow participants. “What we’re trying to do is align the idea of climate change with people’s own values,” Kubit said. “[By] answering the question of, ‘what does climate change mean in my life and what am I doing about it,’ we’re hoping to activate people as leaders in the long term.”

The way to sustain change is to make the climate crisis a priority that ties in with people’s closely-held identities — like parenthood, Shrum agrees. If the broad goal of preventing climate catastrophe becomes a part of who people are, it will feed into every decision, from the grocery store to the ballot box.

Mustafa Önder

Children of Men, dark as it is, is also a film about hope (spoiler alert here). Much of the action revolves around a young woman who gives birth to the first baby in 18 years, and our chiseled friend Clive Owen’s attempt to get her to safety.

Toward the end of the film, there’s a scene that wrecks me every time. Owen is escorting his young companion and her infant through a war-ravaged refugee camp. As they walk through lines of heavily armed soldiers and rebels, the baby crying softly in her mother’s arms, everybody stops. Some men kneel. The silence is absolutely heart-wrenching.

Owen’s mission is to get the mother and her baby to a ship that nobody knows for sure is real. The ship is said to be run by an outfit called “The Human Project,” which Cuarón has suggested is “a metaphor for the possibility of the evolution of the human spirit, the evolution of human understanding.”

I’ll hold off on the final spoiler — if you want to know whether the ship arrives, you’ll have to watch the movie. Likewise, if you want to know whether or not our real-life ship is coming, you’ll have to be one of the people working, in so many ways, to make sure that it does. We know what is causing the climate crisis, and we have the tools to solve it., but making it happen will require heroic, Clive Owen-esque efforts from all of us.

Still, what gets people jumping in front of buses, running into burning buildings, if not love for their children? One of the letters, pasted on the wall of the House of Solutions, put it like this:

“We may or may not do enough. Things could go either way. But when you are reading this years from now, by the light of a solar-powered lamp, know that your dad, mom, and millions of others who burned brightly with love for our kids did what we could, when we knew the stakes, as we watched our hearts running around — laughing, singing, playing, and dreaming of the world to be.”