Q. Dear Umbra,

What’s the deal with autonomous zones? I’ve seen pictures on the news of the one in Seattle, but I don’t really get what they’re about. Could they help achieve climate goals?

— Trying to Comprehend Having Autonomous Zones

A. Dear TCHAZ,

It’s a rare opportunity, especially during the time of coronavirus, that I’m able to answer an Umbra question by actually seeing its subject matter with my own eyes! I live in Seattle, just a couple of miles from the (in)famous Capitol Hill Organized Protest, which, until quite recently, was known as the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone. But CHOP or CHAZ or whatever you want to call it, the area is sparking a lot of interest — and confusion — about the purpose of autonomous areas.

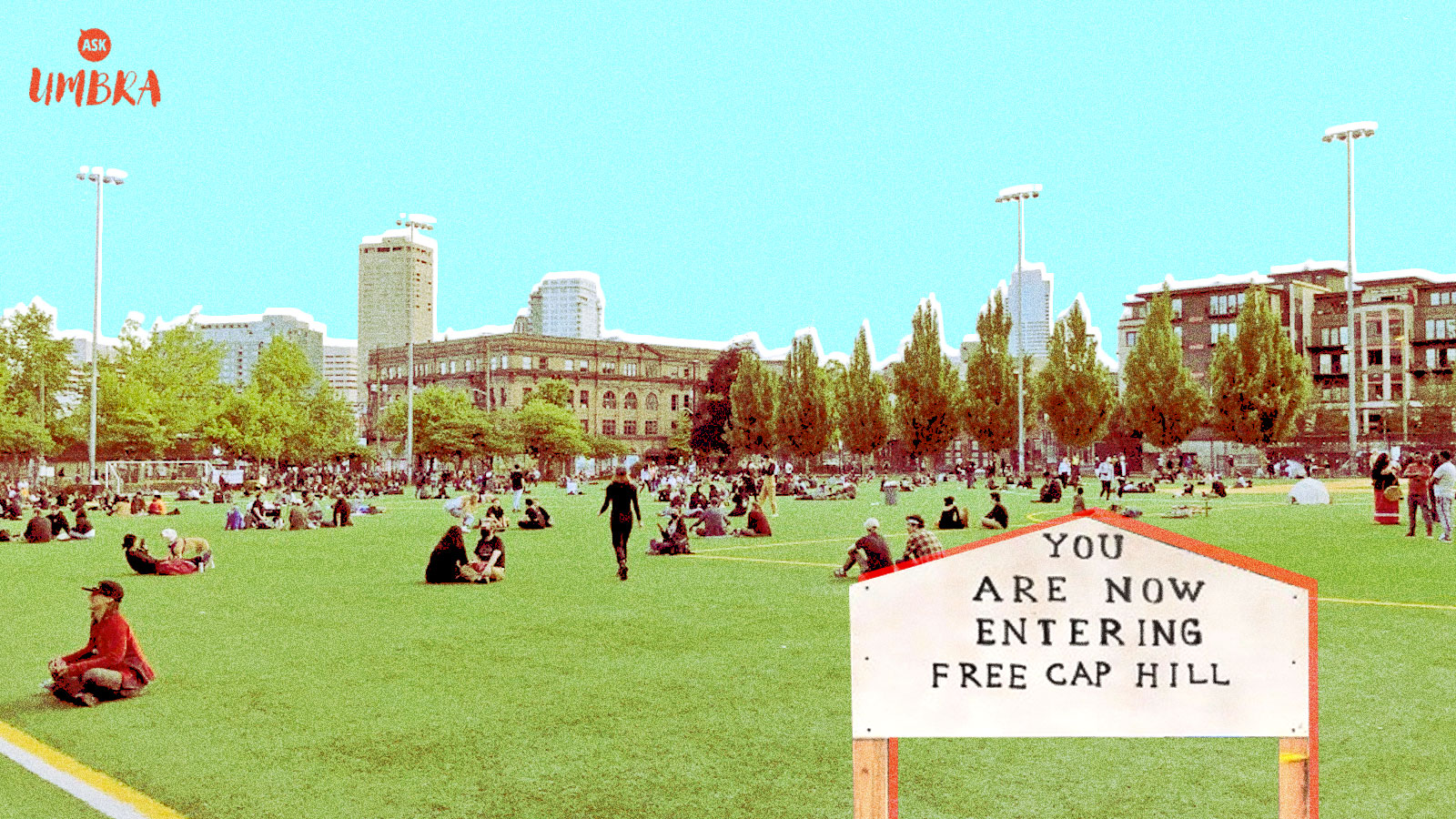

I visited the CHOP, a six-block stretch of Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood that community members have declared a “police-free” zone, twice in the first week after it came into being. Despite the Fox News-perpetrated rumors, the space did not resemble a barbed wire enclosure with Uzi-armed guards at the gates forcing any visitors to pledge their firstborn children to ANTIFA warlords. Instead, I came upon young people painting the streets, an alcove of couches dubbed a “conversation café,” a few tank top-clad volunteers hard at work digging fresh garden beds, and circles of would-be revolutionaries debating what the hell the CHOP should be.

It was quite a transformation. If you had come upon the exact same block four months ago, you would have been likely to spot moneyed millennials on their way to brunch or fiercely engaged in blackout-drunk couple fights, depending on the time of day. (The median home price in 2019 for the surrounding neighborhood was around $1 million and the median household income was around $100,000.)

Then about a week and a half ago, police vacated the neighborhood’s East Precinct, which had been the site of several recent protests against racist police brutality. Some of those protests had become violent as police officers clashed with demonstrators, firing rubber bullets and spraying participants with tear gas and mace. So when the police “abandoned” the building, some protesters moved in, removing and repurposing police barricades to block off the area and declaring it an “autonomous zone.” (Organizers have since walked that description back to make clear that they are not seceding from the United States, as photojournalist Alex Garland reported.)

A sign and repurposed barricades mark the border of the Seattle CHOP. Eve Andrews / Grist

An autonomous zone is an area that a group of people declares to be self-governing through what is essentially squatter’s rights; if you hang out for long enough and no one makes you leave, I guess it’s yours for now! Historically, such zones have been born after a group of people takes major issue with how the space was being governed before. As my colleague Kate Yoder wrote earlier this week, they are part of a long tradition of utopian experiments, though the ultimate fate of many of those zones has been less than idyllic.

In the case of the Seattle CHOP, leaders — most of whom have remained unidentified — have issued a list of demands to Seattle’s city government that they say must be met before they cede back the area. Those demands include law enforcement-specific actions — defund the police, free protesters who have been arrested, pay damages to those who have been brutalized by police, etc. — but also this requirement: “We demand the de-gentrification of Seattle, starting with rent control.”

That brings me to the second part of your question, TCHAZ. Not only is it possible that autonomous zones could be part of a climate solution, one could argue that the Seattle CHOP’s demands are already inherently pro-climate. Environmental justice activists say that addressing gentrification and dismantling white supremacy are necessary steps to prime the world for a just transition from fossil fuels.

A volunteer in the Seattle CHOP gathers items for trash and recycling. Eve Andrews / Grist

Let’s focus on the gentrification angle for a moment. If you are a regular reader of this column, you are likely aware of my position on the role of dense urban living for a more climate change-resilient future. It’s easier to lead a lower-emissions lifestyle in a neighborhood where you don’t need a car and can access everything you need by foot, bike, or public transit, and more compact homes with smaller footprints require less energy.

Access to that kind of denser, more efficient infrastructure is critical to shrinking the carbon footprint of a growing population — and yet, the skyrocketing costs of this kind of housing in cities across the nation mean those homes are out of reach for all but the very wealthy. That’s certainly the case here in Seattle, where over the past 10 years the Black population in the suburbs surrounding the city has grown by 50 percent as a result of Black Seattleites being priced out of more central neighborhoods.

In Ta-Nehisi Coates’ 2014 magnum opus for The Atlantic magazine, “The Case for Reparations,” he pointed out that Black families have been systematically deprived of acquiring wealth through land by redlining policies and predatory lending practices. As a result, white families today enjoy roughly 10 times the wealth of Black families, on average. “It’s important for people to understand that we live in an economic system that’s based on ownership of land,” said Marcus Henderson, a Black resident of the Columbia City neighborhood in Seattle and the organizer of the community garden at the CHOP. “Unless we truly give back the land to Black and indigenous people, they’ll never be able to hold onto wealth.”

A sign marks the site of a community garden in the Seattle CHOP. Kate Yoder / Grist

One strategy for pushing against large societal crises like gentrification (and climate change) is to raise awareness. Autonomous zones achieve this goal by pushing boundaries — both literally and figuratively. And Henderson says the outsider feeling that privileged residents of Capitol Hill might have in the CHOP links back to what Black residents have experienced through gentrification. “The neighborhood now feels what it’s like for an outside community to come in,” he said.

But not everyone agrees that occupied areas like the CHOP are the most effective vehicles to promote change. Victoria Beach is a Black community leader in the Central District, the neighborhood immediately bordering Capitol Hill, and a lifelong resident of the area. Fifty years ago, the population of the Central District was 75 percent Black; today, that figure is around 15 percent. Beach says she has watched all of her siblings get priced out of the neighborhood and pushed into the suburbs.

For several years, Beach has held the role of chair of the African American Community Advisory Council, a liaison group to keep an open dialogue between the community and the police department, in spite of the fact that her family has suffered several incidents of police brutality and racial profiling. She said she was “blown away” that so many people — including white allies — have been moved to take action in the wake of the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, but that she still believes the occupation tactics in the CHOP to be counterproductive.

She expressed dismay, for example, that she didn’t recognize any of the self-identified leaders of the CHOP as members of the neighborhood Black community. She also found the white presence in the CHOP overwhelming. (I reached out to one of the CHOP leaders for comment and did not get a response.)

“I’m just furious that I feel like the white community has stolen our spotlight,” she said, though she acknowledged that her group’s relationship with the police department was also met with criticism from some members of the local Black community. “By putting [the CHOP] down there, the whole focus and meaning is lost, and I’m going to fight hard with everybody to get it back. I said, this is white privilege at its finest. I don’t know, it’s so hard what I’m seeing.”

For his part, Henderson said that while he supports the vision of the CHOP, he would prefer to be putting in gardens in Black Seattle communities that stand to benefit from them more. But in the CHOP, he argues, “we can bring and transfer resources from people who have privilege and power and want to see this change.”

People in the Seattle CHOP mill in front of a sign designating the East Precinct Police Station “property of the people.” Eve Andrews / Grist

When I visited the CHOP a second time last week, I approached a white woman carrying a sign that read “Residents Affinity Group.” She told me that her goal was to signal to other white people — “Karens,” she said — coming to the area that the people who lived in Capitol Hill supported the goals of the movement. When I asked if I could interview her, she told me I should really be speaking with nonwhite residents; when I asked if she could suggest someone, she said she didn’t actually know any.

Even as “autonomous” spaces go, the CHOP is in its very, very early stages; it’s much different today than what it was even a week ago, and who knows if it will exist a week from today! But your question is about whether such an occupation can achieve larger goals. And a really bold action like taking over a chunk of a popular neighborhood definitely seizes the attention of people in power as a sign that you’re serious about major change.

What happens next is less clear. Other — if smaller-scale — occupations have yielded meaningful results in Seattle before: A Native American reclamation of 20 acres at the former Fort Lawton military base in the 1970s resulted in the Daybreak Cultural Center, and the Latino occupation of an abandoned school in Beacon Hill made the Centro de la Raza. One goal of the CHOP, Henderson told me, is to turn the police precinct into a similar resource center for the community.

And if you want to do something really transformative, like alter the landscape of cities and reduce emissions to combat climate change? I think one lesson of the CHOP is that it’s important to have the buy-in and support of the community that is already there and has been historically invested in working toward those goals.

Revolutionarily,

Umbra