WAIMEA, HAWAII — The island of Kauai, Hawaii, has become Ground Zero in the intense domestic political battle over genetically modified crops. But the fight isn’t just about the merits or downsides of GMO technology. It’s also about regular old pesticides.

The four transnational corporations that are experimenting with genetically engineered crops on Kauai have transformed part of the island into one of most toxic chemical environments in all of American agriculture.

For the better part of two decades, BASF Plant Science, Dow AgroSciences, DuPont Pioneer, and Syngenta have been drenching their test crops near the small town of Waimea on the southwest coast of Kauai with some of the most dangerous synthetic pesticides in use in agriculture today, at an intensity that far surpasses the norm at most other American farms, an analysis of government pesticide databases shows.

Each of the seven highly toxic chemicals most commonly used on the test fields has been linked to a variety of serious health problems ranging from childhood cognitive disorders to cancer. And when applied together in a toxic cocktail, their joint action can make them even more dangerous to exposed people.

Last fall, the Kauai County Council enacted Ordinance 960, the first local law in the United States that specifically regulates the cultivation of existing GMO crops, despite an aggressive pushback from the industry, which contends that current federal regulations suffice. The law’s restrictions will go into effect in August.

The GMO field experiments are supervised by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the pesticides have the U.S. EPA’s stamp of approval. But where some see oversight, others see blinders. Kauai County, which encompasses the entire island, contends that the federal agencies have ignored the health impacts while allowing the corporations to freely pursue profits, so it has claimed authority to regulate the pesticides used within its borders.

Pesticides on KauaiAnti-GMO activists on Kauai.

Ordinance 960 creates no-spray buffer zones near schools and other buildings where people live, work, or receive medical care, but falls far short of a complete ban on GMO crops. In recent weeks, however, Kauai residents have proposed an amendment to the county charter that would tighten the new regulations a lot further. If approved in a countywide vote, it would ban all GMO cultivation until the companies can prove to the county’s satisfaction that their pesticide usage does not harm public health.

The agribusiness giants are not going to back down without a fight. In January, the companies filed suit in an effort to quash Ordinance 960; a court ruling on the suit is expected in the next few months, before the law takes effect. The companies are also expected to mount a vigorous political campaign to fight the charter amendment and to support a slate of GMO-friendly candidates to compete with pro-960 candidates in the November general election, when the mayor and all seven County Council seats are on the ballot.

“Kauai is Ground Zero for the testing of GMO crops,” said Gary Hooser, a member of the Kauai County Council and an author of Ordinance 960. “It is also Ground Zero for democracy in action.”

Why the locals are fighting

Perhaps no one personifies the battle better than Klayton Kubo, who lives at the east end of Waimea, at the heart of what he calls “poison valley.” He showed this reporter a brief video of himself cleaning the screen covering the window on the street side of his house. Clogged with reddish dirt similar in appearance to volcanic soils found throughout the island, the screen is his house’s last line of defense against the dust. However, it blocks only the biggest chunks, and can do nothing to stop smaller pieces of grit, toxic vapors, and chemical odors that appear to be emanating from DuPont test fields located just beyond the street and Waimea River in front of his house.

Klayton KuboRed dust blows up from a GMO test field.

Kubo began looking for answers to his questions about what’s in the air some 15 years ago. More than once, he says, a DuPont representative came to his house only to lower his head and mutter that it’s “against company policy” to reveal any information about activities on the test fields. Kubo is among 150 of his neighbors who have joined a class action lawsuit against DuPont, seeking damages and an injunction against the use of suspected toxic chemicals.

At the other end of town, the Waimea Canyon Middle School, a health clinic, and a veterans’ hospital line up in front of another GMO test field operated by Syngenta. In two incidents in 2006 and 2008, students at the school were evacuated and about 60 were hospitalized with flu-like symptoms like dizziness, headaches, and nausea. Many people in town blamed the outbreak on blowing dust from the GMO test fields. Steady northeasterly trade winds averaging between 8 and 9 miles per hour blow daily across the test fields and into town. The companies blamed nearby fields of noxious stinkweed.

In an attempt to find out what actually happened, federal, state, and local government agencies in 2010 collaborated to test the air at the school for the presence of 24 kinds of toxic pesticides used on the test fields as well as for chemicals emitted by stinkweed. The study was inconclusive, finding that the “symptoms could be consistent with exposure to certain pesticides, but could also be caused by exposure to volatile chemicals emitted from natural sources, such as stinkweed.” It detected traces of the toxic pesticide chlorpyrifos in the air both inside and outside the school, but said it found “no evidence to indicate that pesticides had been used improperly.” Concentrations of all chemicals were below EPA exposure limits.

But Gerard Jervis, a Honolulu lawyer representing the residents in the class-action lawsuit, said he doubted stinkweed was the source of the problem. Chemicals emitted by stinkweed are found in the air at similar concentrations elsewhere on the island and to his knowledge have never caused any health problems, he said. Moreover, the concentrations of airborne pesticides were found at much higher levels in Waimea than elsewhere on the island.

Jervis also noted that the air quality study did not even try to look for more than 30 specific pesticides that have been used at the GMO test fields since 2007, including two of the most dangerous, paraquat, a weed-killer, and methomyl, an insecticide.

Ordinance 960 was designed to prevent the recurrence of outbreaks like the one at Waimea school.

Why the companies are fighting back

The four agribusiness giants chose to locate their R&D work in the tropical climate of the Hawaiian Islands because they say it enables them to work their fields year-around, expanding the annual growing calendar to three or four seasons while compressing the time it takes to develop a new genetically altered seed by nearly half.

Ian Umeda

The companies produce much more than newfangled seeds. At their core, they are large chemical companies that manufacture many types of agricultural chemicals. A major chunk of their income is generated from the sale of pesticides to farmers on the U.S. mainland. The farmers are told that they must use the chemicals in order to protect their pricey GMO crops from never-ending attacks by bugs and weeds. The agribusinesses are like printer manufacturers that make their money selling high-priced ink cartridges.

An early achievement was Monsanto’s development of “Roundup Ready” corn and soybean seeds that can resist applications of the herbicide glyphosate, also known as Roundup. Ideally, on Roundup Ready fields, the crops live while the weeds die.

However, in the 18 years that Roundup Ready seeds have been on the market, they have lost much of their effectiveness. The crops still survive, but on many farms across the U.S. a significant percentage of the weeds have mutated to the point that they no longer die as intended. Increasingly, varieties of herbicide-resistant superweeds are sprouting up in fields worldwide, wherever Roundup Ready crops are grown. On some fields, insecticide-resistant superbugs such as the corn rootworm are creating an additional set of problems for GMO farmers.

The companies have responded by trying to create new seed varieties that can coexist with other chemicals that they hope can be used to enhance or replace Roundup. For example, Dow has developed new corn and soybean seeds that are resistant to 2,4-D, an older herbicide that was an active ingredient in Vietnam War-era Agent Orange and has been linked to reproductive problems and cancer. The company has asked the USDA to approve the seeds in hopes that a new generation of herbicide-tolerant crops can come to the market. Dow has given no assurance that overuse of 2,4-D won’t create additional new varieties of superweeds.

Hooser said Dow officials told him that research conducted on Kauai played a key role in the development of 2,4-D-resistant seeds.

What’s blowing in the wind across Kauai

Some of the pesticides in use on the test fields around Waimea are toxic enough to pose a serious health threat to its population of 1,855, even when used according to directions. These are classified as “restricted use pesticides,” meaning they are more tightly regulated by the EPA than “general use pesticides.” The restricted-use chemicals applied most heavily on the GMO test fields of Kauai are alachlor, atrazine, chlorpyrifos, methomyl, metolachlor, paraquat, and permethrin.

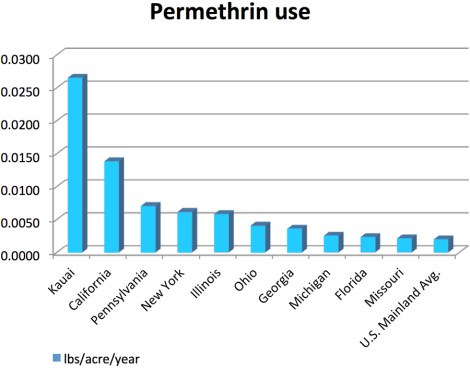

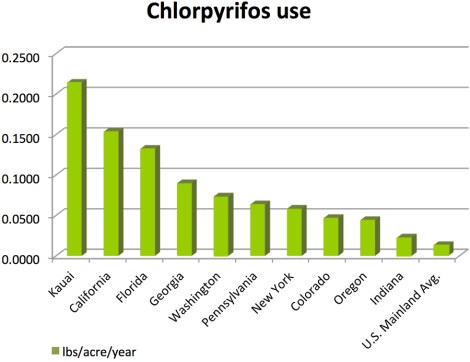

The four agribusiness companies with test plots on Kauai have voluntarily released data about how much of the restricted pesticides they used on the fields from December 2013 through April 2014; the information is now available in a database on the Hawaii state government website. We compared that information to 2009 data from a U.S. Geological Survey database on pesticide usage in the United States.

The four agribusiness companies with test plots on Kauai have voluntarily released data about how much of the restricted pesticides they used on the fields from December 2013 through April 2014; the information is now available in a database on the Hawaii state government website. We compared that information to 2009 data from a U.S. Geological Survey database on pesticide usage in the United States.

We found that annualized pounds-per-acre usage of the seven highly toxic pesticides on Kauai was greater, on average, than in all but four states: Florida, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Indiana. (For the purpose of this comparison, the analysis assumed the chemical companies used pesticides on all 12,000 acres they control on the island. It also assumed that farmers used pesticides on all 314 million acres of harvested cropland on the mainland U.S. Yes, there are organic farms that don’t use pesticides, but they encompass just slightly more than 1 percent of U.S. agricultural land, according to the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service.)

As shown in the charts below, the per-acre usage of the bug killers permethrin and chlorpyrifos on Kauai is each projected to be significantly greater on average than in California, and more than 10 times greater than the national average.

The analysis also projects that Kauai would rank second nationally for methomyl, fifth for metolachlor, sixth for alachlor, ninth for paraquat, and 23rd for atrazine.

The analysis also projects that Kauai would rank second nationally for methomyl, fifth for metolachlor, sixth for alachlor, ninth for paraquat, and 23rd for atrazine.

Steve Savage, a former manager of research at DuPont and a former professor at Colorado State University, has also found that the overall pounds-per-acre pesticide usage on Kauai is among the highest in the nation, but he said that 98 percent of the pesticides used on the island are general-use ones that are less toxic than a cup of coffee.

Savage may be right on that point, but the remaining 2 percent give serious cause for concern. “Different pesticides can vary in something like their toxicity to mammals by more than a thousand-fold,” he said.

Six of the seven restricted-use pesticides used most heavily on Kauai are suspected of being endocrine disruptors, which can cause sexual-development problems in humans and animals, according to the EPA. Tyrone Hayes, an endocrinologist at the University of California-Berkeley, has raised particular concerns about the potentially gender-bending effects of even tiny amounts of atrazine. His reputation has been viciously attacked by Syngenta, as reported by The New Yorker.

A study published in March in the British journal The Lancet Neurology found that chlorpyrifos, a neurotoxin, is one of a dozen chemicals commonly found in the environment that “injure the developing brain” of children.

Four of the seven heavily used restricted pesticides are suspected or likely carcinogens. And between them, the seven have been linked to, among other things, neurological and brain problems and damage to the lungs, heart, kidneys, adrenal glands, central nervous system, muscles, spleen, and liver.

Combine the pesticides together and the effects could be even worse, especially in the developing bodies and brains of children and fetuses. The EPA knows little about the synergistic effects, or combined killing power, of multiple chemicals when people are exposed to them at the same time, but it recently observed that the joint action of atrazine and chlorpyrifos can result in “greater than additive toxicity.” In other words, the whole cocktail can pack a bigger punch than the sum of its ingredients.

In another example, the combined presence of the insecticides permethrin and chlorpyrifos has been shown to be “even more acutely toxic” than the sum of each, former EPA scientist E. G. Vallianatos writes in his new book Poison Spring: The Secret History of Pollution and the EPA.

As if all that weren’t bad enough, there’s reason to believe that the agri-giants might be violating federal rules about the application of the restricted-use pesticides on Kauai. The rules are supposed to ensure that the pesticides do their damage to bugs and weeds, not kids.

For example, consider Dow’s Lorsban, which consists of about 45 percent chlorpyrifos. Lorsban is the restricted-use pesticide product that’s most heavily sprayed on the Kauai test fields, and may have been the pesticide most responsible for making the children at Waimea Canyon Middle School sick. The EPA prohibits its application whenever the wind blows greater than 10 mph. The average wind speed in Waimea is between 8 and 9 mph, according to the National Weather Service, meaning that on many days the spraying of Lorsban might not be legal.

The EPA says that applicators must “not allow spray to drift from the application site and contact people, structures people occupy at anytime and the associated property, parks and recreation areas, non-target crops, aquatic and wetland sites, woodlands, pastures, rangelands, or animals.” The agency stresses, “Avoiding spray drift at the application site is the responsibility of the applicator.”

In Waimea’s windy climate, it’s a rare day when Lorsban and the other heavily used toxic chemicals can be applied to the test fields without the wind blowing them right into somebody’s face.

—–

See also: GMO giants’ pesticide use threatens rare Hawaiian species

These articles are part of a collaborative media effort sponsored by The Media Consortium and made possible in part by a generous grant from the Voqal Fund. Read more stories at WTFcorporations.com.