To burnish their green credentials, companies have long paid to plant trees or protect forests in the hopes that nature will absorb their greenhouse gas emissions. Shopify, the Canadian company that runs e-commerce sites, wants to take a more hands-on approach — by paying a Texas venture to pull carbon dioxide from the sky and store it underground.

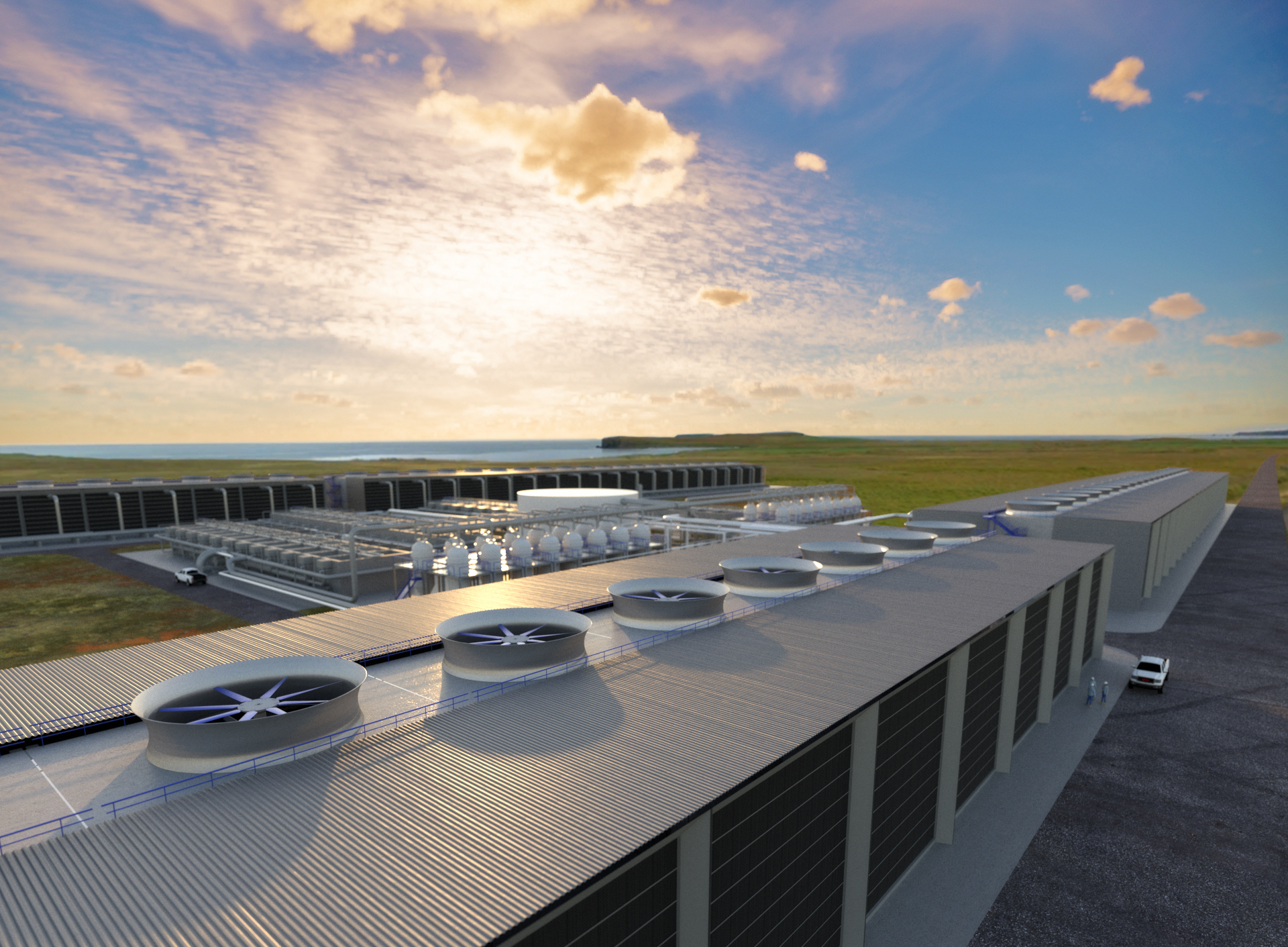

Shopify struck a deal this month with Carbon Engineering, which is about to start building a sprawling “direct air capture” facility in West Texas with its partner 1PointFive. Their plant, expected to be the largest of its kind, will use huge fans to draw in air and churn out pure CO2. Shopify has agreed to “buy” 10,000 metric tons of the gas that will be permanently sequestered in deep rock formations.

The initiative comes as corporations are redoubling promises to address climate change. Tech firms, airlines, and oil-and-gas giants have all recently pledged to reach “net-zero” emissions by 2050 — a loosely defined strategy which generally means they’re working to cut new emissions and reverse past pollution. Climate scientists say the world must now do both to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius by mid-century.

As part of those efforts, companies as wide-ranging as Microsoft, Audi, ExxonMobil and Stripe are investing in businesses developing cutting-edge technologies that remove carbon from the atmosphere and lock it away. Selling CO2-removal by the ton offers a way to fund these enormously expensive ventures while allowing companies to claim credit for (eventually) trimming their carbon footprints.

“We firmly believe these types of frontier technologies are going to be a necessary part of the climate solution,” said Stacy Kauk, director of Shopify’s sustainability fund. Along with the deal it struck to remove 10,000 tons in Texas, the ecommerce software company is buying 5,000 metric tons of carbon removal from Climeworks. The Swiss firm is expanding its direct air capture plant in Iceland and developing a new one in Norway.

Shopify aims not only to curb its own carbon footprint from powering and heating its buildings and employees’ travel — nearly 8,000 metric tons in 2019 — but also to jumpstart broader demand for carbon removal projects by being an early adopter. “As direct air capture gains traction, we’re hoping this purchase, plus other purchases from other companies, will start to scale this service and drive down costs,” Kauk said.

The strategy is likely to catch on with other large businesses and heavy polluters, particularly in hard-to-decarbonize sectors like airlines and steel manufacturing, according to experts. Still, they stressed that these projects shouldn’t replace efforts to slash emissions directly from flying jets, shipping goods, powering buildings, or running factories.

“We need to make sure that we don’t dilute the stringency of an emissions reduction target of a given company,” said Kelly Levin, a senior associate in the World Resources Institute’s global climate program in Boston.

Offsets tied to direct air capture may have certain advantages over, say, planting trees. To start, there’s less guesswork around how much carbon is actually pulled from the sky using big machinery. And gas that’s sequestered deep underground is less likely to escape into the atmosphere than from a forest or wetland, where wildfires, plant disease, and human activity can set CO2 loose.

Projects that remove carbon and permanently store it may also avoid a key criticism of other types of offsets: that they don’t do much for the climate. For instance, a company can pay a nonprofit to protect swaths of the Amazon rainforest from deforestation; the company then claims credits for the CO2 that isn’t emitted as a result of its investment. But if the land isn’t likely to be developed anyway, then it’s impossible to say whether there’s any real benefit.

In Carbon Engineering’s case, the carbon removal and sequestration will only happen if someone pays to do it, said Derik Broekhoff, a senior scientist at the Stockholm Environment Institute who is based in Seattle.

The direct air capture plant in Texas will likely cost hundreds of millions of dollars to develop. At full scale, the facility could capture 1 million metric tons of CO2 every year, according to Carbon Engineering. The Canadian firm is licensing its technology to 1PointFive, a joint venture between a subsidiary of Occidental Petroleum Corp. and the private equity firm Rusheen Capital Management, based in Santa Monica, California.

Much of the captured carbon will be injected into old wells in the Permian Basin to force up remaining oil. But interested customers like Shopify can separately pay for “pure sequestration,” meaning the CO2 would go into long-term storage wells in deep rock formations, according to Steve Oldham, CEO of Carbon Engineering. The service is “a way of allowing anybody to buy negative emissions,” he said.

Construction on the giant fans is expected to start this year, with operations slated to begin in late 2024. Oldham said Occidental is working to find nearby sites for storing CO2 and obtain permits from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which regulates this type of well. Shopify has paid a deposit for the 10,000 tons and will hand over the rest of the money once the carbon is actually removed, said Kauk from Shopify. (She and Oldham declined to disclose financial details. Kauk said only that Shopify is investing $5 million annually to address climate change, of which at least $1 million is devoted to capturing and permanently storing atmospheric carbon.)

Current estimates put the price of sucking carbon from the sky at about $600 for every metric ton of CO2. Oldham said he expects it to drop to around $100 to $150 per metric ton once more facilities are built.

Despite the potential advantages, using direct air capture to reduce a company’s carbon emissions still raises questions and concerns, Broekhoff and other experts said.

United Airlines, for instance, recently announced plans to make a “multimillion-dollar investment” in 1PointFive, which is leading construction of the Texas facility. United said the investment will help to meet its goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 50 percent by 2050. But the airline isn’t buying a share of pure sequestration; it’s backing the entire venture. So it’s unclear how much United’s money leads to “additional” carbon removal, since the project is already underway. It’s also hard to say when, or by how much, this support will translate into actual emissions reductions.

“Investments are critical, but let’s not imagine that investing in and testing the technology is the same as actually using that technology toward climate goals,” said Simon Nicholson, co-director of the Institute for Carbon Removal Law and Policy at American University in Washington, D.C. In a blog post, Nicholson and colleagues said the United announcement should be “applauded” as well as the subject of “careful scrutiny.”

Given the high cost and technical complexity of these projects, there’s also the risk that some facilities won’t be built or operate as planned. If companies invest now and subtract the captured carbon from their current footprints, they may wind up overestimating the actual results.

So that outsiders can gauge whether carbon removal projects are delivering on their promises, developers should provide detailed, standardized, and accessible data, according to CarbonPlan, a nonprofit in California. But that’s not currently happening, researchers there said. CarbonPlan recently evaluated dozens of proposals for nature-based and technical solutions and said it couldn’t independently validate claims owing to “missing, incomplete, or duplicative” information.

“Without stronger disclosures, it’s almost impossible for companies — or the public — to know with confidence whether these activities are working,” CarbonPlan’s researchers wrote.