Police subdue a protester at an Occupy Wall Street rally in New York City.Photo: Audrey Pilato

Police subdue a protester at an Occupy Wall Street rally in New York City.Photo: Audrey Pilato

Over the past couple of weeks, the fight between “the 99%” and the powerful Wall Street and Washington elite has devolved into a street battle between protesters and the police. Black-suited cops have pepper sprayed peaceful protesters, bloodied kids who blocked New York streets, and clubbed an old lady. It’s too bad — for everyone involved.

It’s easy to scapegoat people like John Pike, the UC Davis police officer who doused a group of students with pepper spray — and was promptly escorted, along with the rest of his squad, off of the green by a group of outraged students. (If all you’ve seen is the pepper spraying, you’ve gotta watch the scene that followed, captured in this YouTube video. These kids showed incredible chutzpah and restraint.)

But the problem obviously goes beyond individual officers. “Let’s not pretend that Pike is an independent bad actor,” Alexis Madrigal wrote an incisive piece in The Atlantic. “If we vilify Pike, we let the institutions off way too easy.”

Writing in the Guardian, author Naomi Wolf went so far as to suggest that Congress itself advised — and the Department of Homeland Security coordinated — a violent nationwide crackdown in an effort to quell dissent that might threaten lawmakers’ pocketbooks.

Of course, those crazy kids on the Interwebs just had a great time making a mockery of the cops.

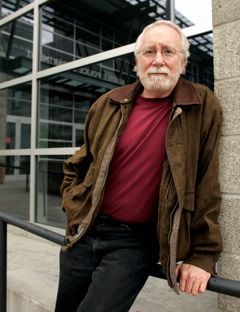

For a little insight into the issue, and some perspective from the police side of the line, we called Norm Stamper. He was chief of the Seattle Police Department when all hell broke loose during the 1999 meeting of the World Trade Organization. He has spent a good deal of the decade since then trying to make sense of what happened, and doing his best to prevent it from happening again.

Former Seattle police chief Norm Stamper calls the 1999 WTO protests “the worst week of my career.” Q. Take us back to 1999 and the first couple of days of the WTO protests in Seattle.

Former Seattle police chief Norm Stamper calls the 1999 WTO protests “the worst week of my career.” Q. Take us back to 1999 and the first couple of days of the WTO protests in Seattle.

A. We thought we were ready. We had put in 10,000 hours of training. We had sent officers around the country. We had studied what had happened at previous international financial conferences.

Monday [the first day of the WTO meeting] comes and goes with a few incidents, with many thousands of protesters on the streets. They’re praising us for our friendliness, our restraint … On Tuesday morning, however, starting at 2 or 2:30 in the morning, we get reports from our officers that large contingents of protesters, some of them holding gas masks, were starting to converge on the downtown area.

When the sun comes up, we get a real sense of how big this demonstration is … We knew there would be a big crowd, but we had no idea it would number into the tens of thousands … I remember standing outside the Sheraton and seeing a thin tan line of sheriff’s deputies who had been assigned to keep demonstrators out of the parking garage. The Sheraton was key. It was a venue for the WTO conference. Large numbers of conferees were staying there.

We continued to ask people to leave traffic lanes open in case we needed, in the event of an emergency, to get a fire truck or a police car or an aid car in there. Those requests met with rejection. By 9:00, the intersection was completely clogged. The demonstrators had sat down, locked arms, and refused to budge.

The police were hopelessly outnumbered. It looked like we had this huge force, but we had cops only in the hundreds when we needed them in the thousands.

Q. Were you afraid at that moment?

A. I was not feeling physical fear … I was feeling fear that this entire thing was going to blow up, get out of hand. The anti-global message, which personally I supported, would be lost. The focus would be on the police.

Then I made one of the biggest mistakes of my career.

During the 1999 WTO protests police tried to clear streets using tear gas — a tactic that backfired when the protests turned violent.Photo: Isabel Esterman Q. What did you do?

During the 1999 WTO protests police tried to clear streets using tear gas — a tactic that backfired when the protests turned violent.Photo: Isabel Esterman Q. What did you do?

A. It wasn’t what I did. It was what I did not do. What I did not do is veto the decision to use tear gas.

The operations commander said, “We need this intersection cleared.” The field commander said, “We need this intersection cleared.” Why? Somebody could be in cardiac arrest on the 27th floor of the Sheraton, somebody could be suffering from a gunshot wound … It was the traditional cop in me who supported that decision.

Q. What should you have done? Carried them all out?

A. Couldn’t have done it.

We had way too few cops to do what you’re suggesting. So there was no answer, we thought, other than gas. The [real] answer was, somebody could get hurt, we may not be able to get a fire engine through this crowd. But I needed to do a better job of playing the odds.

People got hurt, and a lot of people got gassed over the next two, three, four days. Nobody got killed — we take that as a large consolation prize; it would have been very easy to imagine someone getting killed by an errant rubber bullet to the eye or the head, or people getting trampled in a crowd … But the police department’s response was inadequate all around — the strategy, the tactics, the use of chemical agents on nonviolent, non-threatening demonstrators.

Q. I assume that you’ve been watching videos of Occupy protests and clashes with police. What goes through your mind when you watch that?

A. There are three scenes that compete for the most onerous.

The UC Davis pepper spraying incident stands out in large part because of the casualness with which Lt. Pike sprayed those nonviolent protesters — who were seated, and their heads were bowed. It was very clear that this was somebody who didn’t feel threatened. There was ample room for the cops to get around them if they had to get to the other side of the protest. Here’s a cop who says, “We told you to leave, you didn’t leave, now you’re going to be punished.” It struck me as punitive and utterly foolish and stupid.

Pepper spray and tazers are alternatives to lethal force. So we need to ask ourselves: Is this a situation when Pike or any other cops would pull their guns and start shooting?

We had the batons out and misused in Berkeley. This is traditional mob and riot control training in action. When I became a cop in 1966, we had campus unrest, antiwar demonstrations, civil rights uprisings all over the country. During the long, hot summers, we would march out to the employee parking lot [in San Diego] to do baton training, then march back … It was very military … That’s one of the huge issues that needs to be addressed with the culture of American policing.

Police in Oakland, Calif., used tear gas to clear Occupy Wall Street protesters.Photo: The Black HourThen there’s Oakland — in many respects the worst. The police were uniformed in all black outfits, wearing catcher’s shin guards and ballistic helmets. I did not see badges or nametags or anything other than this incredible, formidable image that looked anything but human. They were standing there firing tear gas into the crowd. That evoked WTO for me more than any other of these incidents.

Police in Oakland, Calif., used tear gas to clear Occupy Wall Street protesters.Photo: The Black HourThen there’s Oakland — in many respects the worst. The police were uniformed in all black outfits, wearing catcher’s shin guards and ballistic helmets. I did not see badges or nametags or anything other than this incredible, formidable image that looked anything but human. They were standing there firing tear gas into the crowd. That evoked WTO for me more than any other of these incidents.

It’s very clear that most law enforcement agencies have learned little or nothing from 1999.

Q. 1999, sure — what about those long, hot summers in the 1960s?

A. After the ’60s, we had blue ribbon panels look at the cause of rioting and the role of police in either instigating or enflaming this type of emotion. We began the slow, painstaking process of reaching out to communities and rebuilding the trust that had been lost.

In 1973, I headed a partnership designed to demonstrate that you could forge an effective partnership with your community, that you could make decisions in the interest of crime fighting and building a better relationship with the community. Do the math: You’ve got one cop on a beat of tens of thousands of people. By building a true sense of responsibility within the community and in the mutual objectives of law enforcement and citizens, you’re going to get a much safer community and a much healthier community.

Enter the drug war … The drug war began to chip away at community policing. Even in very small rural police departments, you have SWAT teams. You have very small police departments with armored personnel carriers and military grade weapons and ammunition and military tactics. You hear that somebody’s got half a lid [about a half an ounce] of weed in their home and you’re going to mount an assault … It creates a certain attitude that makes the whole thing reducible to us vs. them.

Then you have the war on terror. The federal government, mostly under the Bush administration, is handing out military tools, equipment, and weaponry to local police departments. Nobody who’s seen the images of those towers coming down or the aftermath of the crash of the plane into the Pentagon or that field in Pennsylvania is ever going to forget that. Every one of us has a stake in homeland security. The question is, have we overreacted?

Quiz question: Is this a scene from 1999 in Seattle or 2011 at an Occupy Wall Street rally? *Photo: Steve Kaiser Q. Is the recent response to the Occupy movement creating a new generation of radicals — and is that such a bad thing?

Quiz question: Is this a scene from 1999 in Seattle or 2011 at an Occupy Wall Street rally? *Photo: Steve Kaiser Q. Is the recent response to the Occupy movement creating a new generation of radicals — and is that such a bad thing?

A. I really do support, 100 percent, the purpose of Occupy. I am in the 99 percent. I don’t know a single police officer who’s in the 1 percent. We’re all affected by corporate greed and Wall Street malfeasance. There’s something drastically and seriously wrong with this country. It is affecting the environment. It is affecting the infrastructure. It is affecting the dwindling middle class.

It’s wonderful that we now have attention focused on what the real problem is. That’s just cool. What is not cool is those purporting to represent the 99 percent who offend large portions of the 99 percent with their tactics … There’s got to be a way to take this movement and help it evolve so that it really wins hearts and minds. Then we will see real political and economic change. We will begin to see social justice.

It’s going to take time to rebuild that trust [between the police and the Occupy movement]. But it has to happen. Otherwise the focus is not on corporate greed and people losing their mortgages and their jobs. It really comes down to this for me: How do we mobilize, organize politically in such a way that we don’t turn off the critical mass that we need to make change in this country?

* The last photo was taken more than a decade ago, at the WTO protests in Seattle.