Northeast Ohio’s Cuyahoga River bisects the city of Cleveland, winding its way past parks, railyards, and downtown breweries before emptying out into Lake Erie. The waterway has come a long way since 1969, when the river’s polluted waters caught fire and brought national attention to the nascent environmental movement. Today, people fish in the river, stroll along its banks, and enjoy paddleboarding festivals. But several dozen times a year, heavy rains flood the waterway with raw sewage.

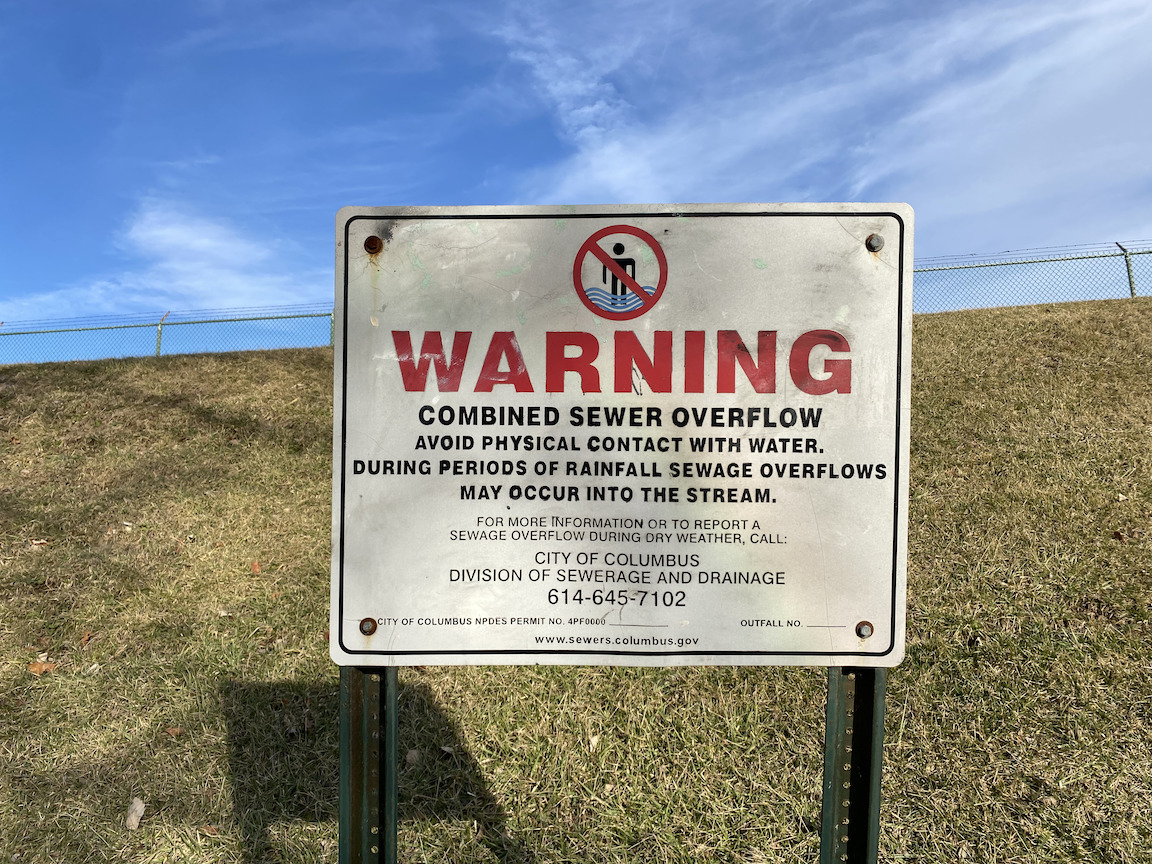

Like many older cities in the Midwest and Northeast, Cleveland’s sewer and stormwater systems are combined, and too often can’t handle the volume of water coursing through them after a heavy storm. The city is a little over halfway through an effort to upgrade this network, building tunnels to store extra wastewater deep underground. But there’s a problem, experts warn: The designs are based on decades-old rainfall estimates that do not reflect current – let alone future – climate risk.

That worries Derek Schafer, executive director of the West Creek Conservancy, a local nonprofit that aims to protect Cleveland’s watershed. “Flooding is natural,” Schafer told Grist. But now, “with a changing climate system, we have higher volumes at quicker intervals, so our systems become even more quickly inundated.”

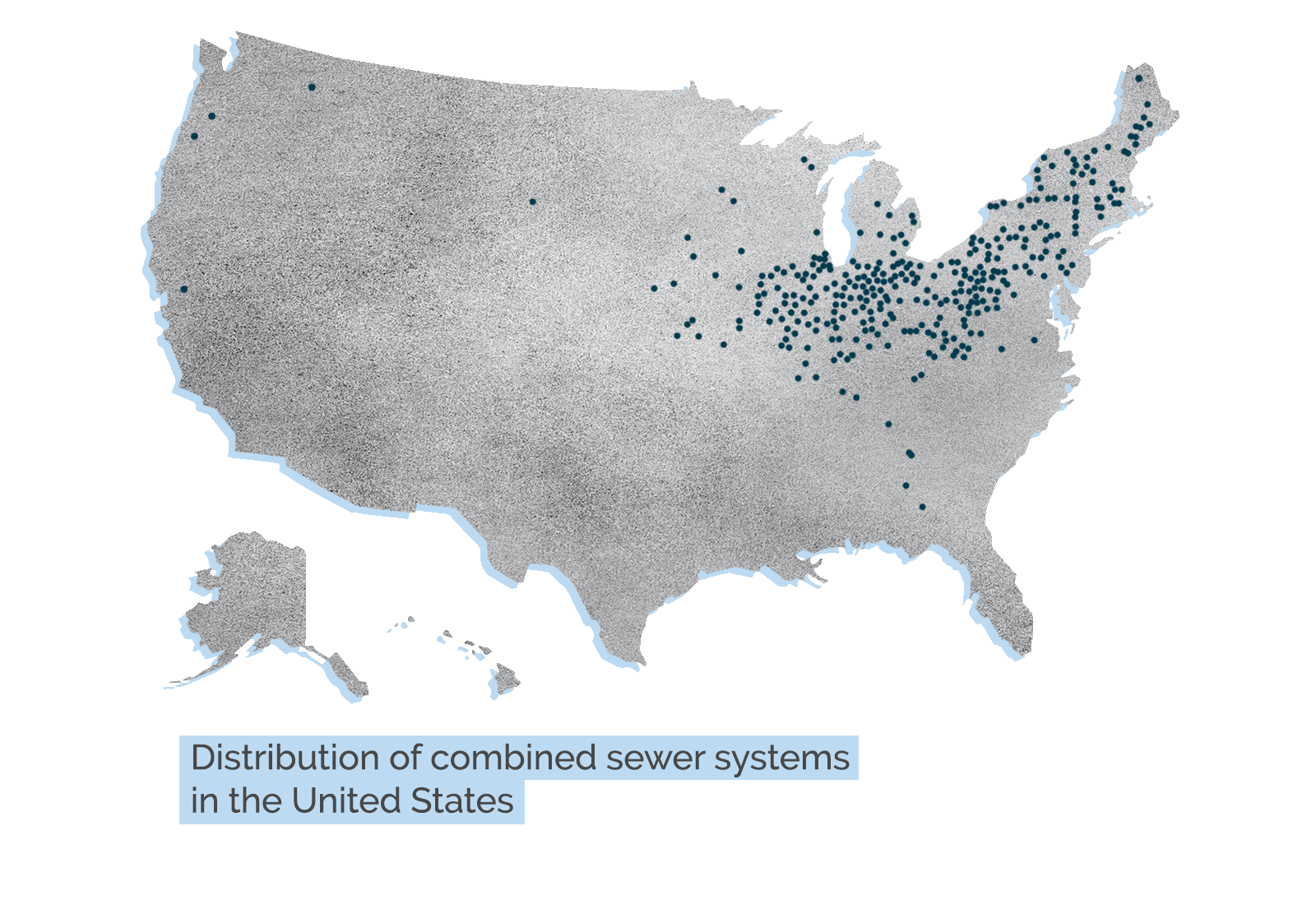

Today, combined sewer systems like Cleveland’s are found in more than 700 communities around the country. In 2004, the last year for which federal data is available, they collectively released 850 billion gallons of raw sewage into rivers, streams, and lakes — closing beaches, polluting drinking water sources, and contributing to harmful algae blooms. The Midwest is home to 43 percent of these systems, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA.

Spilling large amounts of sewage into waterways is a direct violation of the Clean Water Act. And many cities, from Detroit to Chicago, have been forced to sign consent decrees with the EPA, requiring them to reduce the number of overflows by upgrading water infrastructure and capacity. This process, however, can take decades from planning, funding, and permitting to completion, said Becky Hammer, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council who focuses on federal clean water policy. That means the rainfall estimates that dozens of cities use to design their billion-dollar projects are already obsolete by the time they’re finished. The government’s own rainfall estimates are also outdated — it last released figures for Ohio, for example, in 2004 — making planning difficult even if updates were required.

Youngstown, Ohio finalized a $160 million long-term control plan for sewage overflows in 2015 based on rainfall data from the early 1980s. It’s currently in the second phase of its plan, which involves constructing a “wet-weather facility” to store and treat excess sewage and stormwater during periods of heavy rain. Indianapolis is halfway through a $2 billion tunnel project that was designed more than 20 years ago, using precipitation estimates from 1996 to 2000. Chicago is in the final stage of a nearly $4 billion effort to construct 109 miles of tunnels and three reservoirs that was designed in 1972, then updated based on modeling conducted in 2012.

Now, climate change is setting these infrastructure projects even further behind. In the decades since cities’ plans were first approved, storms in the Midwest have grown more frequent and intense. Total annual precipitation in the Great Lakes region has increased by 14 percent, according to research from scientists at the University of Michigan, and the amount of rainfall from the heaviest storms has grown by 35 percent.

The EPA doesn’t instruct cities to consider climate change projections in their proposals, despite a report from the agency finding that “many systems could experience increases in the frequency of [sewage overflow] events beyond their design capacity.” A provision that would have required projects receiving federal funding to conduct climate change assessments was struck from the bipartisan infrastructure bill before its passage last year, Hammer said.

“There are thousands of people [with] sewage and floodwater either backing up into their homes, or running off streets into their basements, damaging property and threatening their health,” Joel Brammeier, president of the nonprofit Alliance for the Great Lakes, told Grist. It is a “failure to modernize our water infrastructure to deal with the reality that people are facing across the Midwest.”

The issue is gaining new urgency with an infusion of federal funding from November’s bipartisan infrastructure bill expected to hit state coffers in the coming months. Though cities haven’t yet figured out exactly how they’re going to use the funding or how much they’ll receive, the package includes $55 billion for water, wastewater, and stormwater management over five years. Biden’s proposed Build Back Better bill, which is currently stalled in the Senate, also includes $400 million per year directly to deal with combined sewer systems.

Cleveland started the overhaul of its water infrastructure system in 1994 under the federal Combined Sewer Overflow Control Policy, and work got underway after signing a consent decree with the EPA in 2010. The $3 billion initiative, known as Project Clean Lake, was designed using rainfall data from the early 1990s. The project’s seven new tunnels — three of which are complete, with another operational next year and three others in the construction and design phases — are built to capture most of the runoff from the “largest-volume storm” in a “typical year,” which would dump 2.3 inches of rain in 16 hours, said Doug Lopata, a program manager for the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District.

Since Cleveland began planning Project Clean Lake, however, climate impacts have gotten worse. In September 2020, Cleveland received nearly four inches of rainfall in 24 hours, the third-highest total for a single day in the city. Half of the top ten rainfall days in the city have occurred since 2000, with more than 3.5 inches of rain falling in a day in 2005, 2014, and twice in 2011. Looking ahead, more intense rainfall in the 21st century “may amplify the risk of erosion, sewage overflow, interference with transportation, and flood damage” in the Great Lakes region, Michigan researchers found.

Despite these changes, Lopata said the sewer district isn’t planning to change the structure or design of Project Clean Lake, which aims to capture 98 percent of the water that would otherwise result in sewage overflows. Lopata believes that goal will still be achieved, even as climate change stresses the system. And even if sewage overflows aren’t eliminated entirely, he said, they’ll be reduced enough to keep the sewer system in compliance with the EPA. However, Lopata also said the district is monitoring rainfall data from the past decade and conducting an internal study to learn more about how the “typical year” has changed.

Anticipating greater and more frequent rainfall doesn’t just mean building bigger tunnels to accommodate it, though. Brammeier said cities will have to implement more of what’s known as “green infrastructure” — restoring wetlands that can absorb water and removing impervious surfaces like asphalt to reduce the amount of water that ends up in combined sewer systems in the first place. That’s going to require “a new way of thinking about doing water infrastructure at a large scale,” Brammeier said.

“You can’t build a tunnel big enough to stop the impacts of climate change,” Brammeier said. “You’ve got to think about how we’re going to make our water [infrastructure] more resilient in a more integrated way than we’ve thought about it in the past.”

Some cities are waking up to that message. Project Clean Lake includes $42 million in green infrastructure investments, and Detroit developed a 15-year green infrastructure plan to replace a tunnel project that was canceled in 2009. Milwaukee, which completed its own “deep tunnel” in 1993, now aims to eliminate sewer overflows entirely by 2035, capturing 50 million gallons of runoff with green infrastructure alone.

While these improvements are progress, they’re likely not enough to prepare for what’s ahead, Brammeier said, and that even agencies that invest in resilient infrastructure now will need money to maintain it. Detroit’s calculations for how much rainwater the system will capture are based on data only up to 2013, and the plan states that “climate change is ignored” in this modeling. Milwaukee, which commissioned a report examining the sewer system’s vulnerability to climate change in 2014, has yet to implement many of its recommendations, according to a 2019 assessment. The city acknowledged that “continued increases in rainfall intensities and amounts” due to climate change would make it difficult to meet its rainwater-capture goal consistently.

Without significant federal aid, the costs of dealing with sewage-laced flooding are passed on to ratepayers, many of whom can’t afford to pay higher water bills in the first place. The price of water in cities like Cleveland and Chicago has more than doubled over the last decade, according to an investigation by APM Reports. Despite these increases, though, low-income communities still experience the worst consequences of aging infrastructure, Hammer said — including flooded basements from backed-up sewers. That makes funding for climate resilience in these communities all the more urgent.

“The estimates for the nationwide need for wastewater and stormwater projects is in the hundreds of billions,” Hammer said. “So we are not done.”